Aromica Bhattacharya tracks a percussion crate from its invention by African slaves to its eventual acknowledgment as intrinsic to Peruvian cultural heritage.

(A message to the reader in Spanish.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

In 1966, Victoria Santa Cruz, a Peruvian national of African descent, visited Africa for the first time in her life and returned to Peru, proclaiming herself to be “blacker and more Peruvian” than ever. “In Paris, they thought I was African,” she remembers. “They didn’t know that there were Blacks in Peru… In contrast, in Africa they spoke English to me. Because of my clothing and manner of walking they thought I was North American” (Feldman, 2008, p.69). Once back in Peru, she, along with her brother, Nicomedes Santa Cruz, became leading figures in the revival of the Afro-Peruvian dance and music, central to which was the revival of the percussion instrument cajón.

The story of cajón is that of recuperation and revival. Within the tale of the cajón lies the portrait of its Afro-Peruvian maker. Living under the shroud of a systematic invisibility, the cajón lends to its maker the strength to take charge of their own history, albeit steeped in the shackles of colonialism, slavery and race. This tale crosses borders, building bridges seldom witnessed.

History of the slave in Peru

Africans did not travel to Peru driven by their desires. They were taken. They knew little of crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Riding the waves in scores of ships, they came, nameless and faceless, slaves to their Spanish colonisers. Their first mention in record books dates back to 1527 (Del Busto Duthurburu, 2014). As they first stepped ashore, they would have been reminded of the fact that they brought very little along.

As slaves in a foreign land, music wasn’t easy to find. Music fulfilled a functional role in the life of an African slave in Peru. It was the light that guided them and the clock that controlled their hour. Music made the time pass by faster, singing as they sowed rice fields (De cajón Caitro Soto, 1995, p.42).

At first, their desire to play the drums was frowned upon (Rocca Torres, 2010, p.69), and finally it was prohibited altogether (Santa Cruz, 2006, p.15). Their quest for music led them to find rhythm in every object they held. …pots, ladles, pans, machetes, pumpkins, bells, seeds, human and animal bones, canes, bottles, animal skin and innards … and many other articles became “instruments for making music” … (my translation, ibid. p.24).

By day and by night, the empty wooden crates would have been their only true companion. By day it served to carry weight and by night, engulfed in the four walls of their modest dwellings, the empty crates lining the walls were a constant reminder of their nameless existence. Nevertheless, they learned to adapt, slowly learning to call the crate a “cajón”, as was its name in the language of their coloniser.

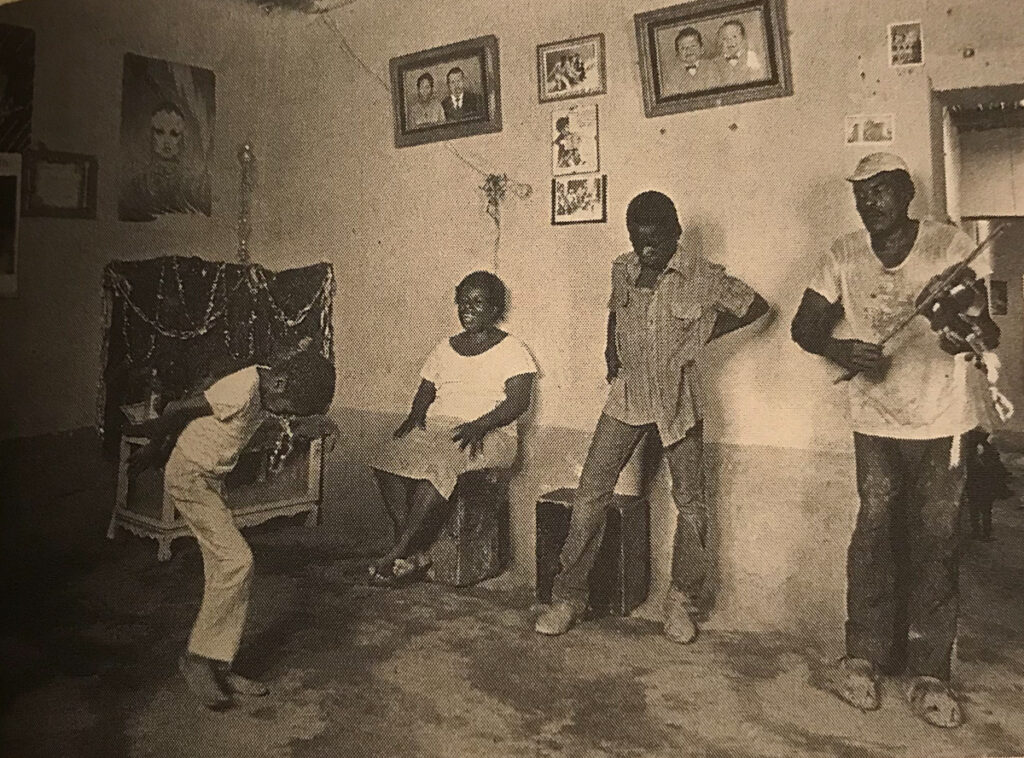

A camaraderie was born, which quickly turned into nightly congregations of fun and frolic. Relationships began to be forged in these nightly sessions of “jaranas”, peppered with music and dance. At first, the “cajons” were silent in their companionship, witness to this transformation. Soon they came to partake, lending themselves to anything and everything, be it as a piece of furniture or an instrument of music. In this moment, the “cajón” was born, a versatile percussion instrument cherished around the world today, and it was in that very instant that its maker, the Afro-Peruvian, came to life.

Don´t get me wrong. It didn’t happen overnight. The cajón was born out of a long process of evolution, which continued long after the colonisers left the country. Many such “instruments” were born and lost in those years of post-colonial apathy. History recorded as many as twenty-one musical instruments (Mayorga Balcazar, 2013, p.298) fashioned and once played by the Afro-Peruvian community, ultimately lost to oblivion, as victims of the debilitating invisibility which shrouded them and their makers both. The secret of the cajón lay in its numbers. It survived because it came in many shapes and sizes. It wasn’t singular in class, instead dependable and durable in its numerosity. Its survival as a musical instrument lay in the very fact that it was functional, and all the while easily replaceable.

Shame and international recognition

Post-colonial Peru treated the Afro-Peruvian with disdain. General consensus agreed that racially they did not belong to the nation. Even numbers couldn’t come to their rescue. National census from the eighteenth century revealed that 60% of the population of Lima were of African descent. By the following century, the numbers had reduced to 4.8% (De cajón Caitro Soto, 1995, p.15). So where did they go? The truth is nowhere: they became invisible. Afro-Peruvians weren’t a minority by way of their numbers, instead, they were marginalised in power and social prestige. The makers of cajón were subalterns in their own country, victims of the shame they internalised for occupying a position of minority. Ultimately, it was their creation, the cajón, that jolted them out of their stupor.

Spain in the history of the cajón

“Eventually, these voices sought to write their own histories when they realized that dominant cultural narratives refused them representation, or worse, misrepresented them.” (Pramod)

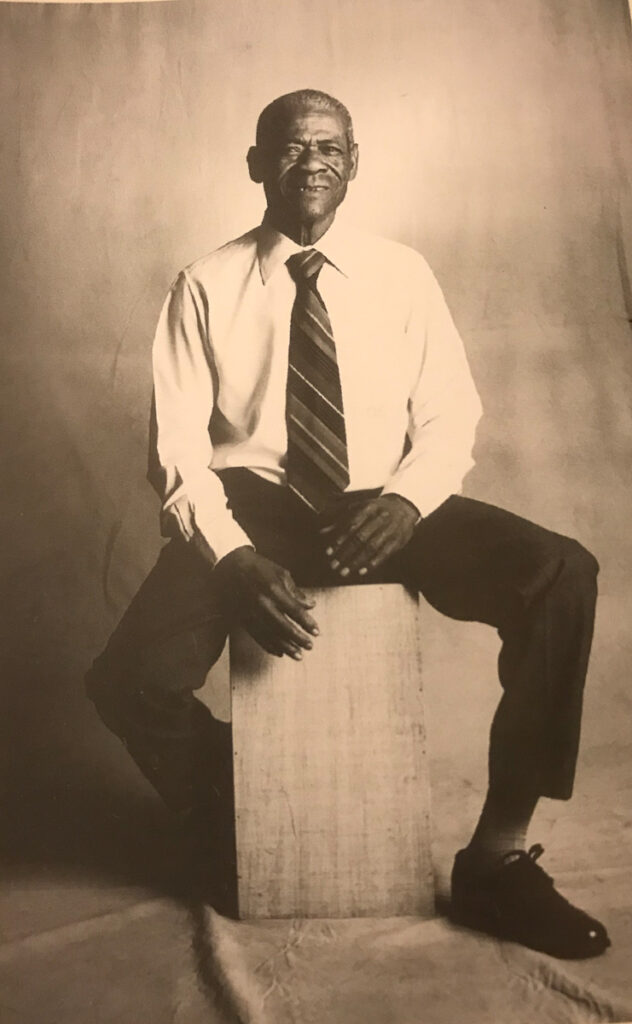

As irony would have it, Spain was pivotal in the revival of the cajón. Neglected in its own home all the while, the cajón gained acclaim internationally. In the 1950s, the cajón gained popularity in the Vals in Spain (Santa Cruz, 2006, p.145), and in the following years, world-renowned Spanish guitarist, Paco de Lucia, introduced it to the Flamenco style of music, having received a cajón as a gift from his friend, the famous Afro-Peruvian musician and cajón player, Caitro Soto. The coupling was so spectacular that many Spaniards began to believe that the cajón had been with them all their life (ibid., p.147). Yet, when Rafael Santa Cruz´s father, a bullfighter by profession, set foot in Spain in 1951 and travelled through cities, small and big, he never once heard the mention of a cajón, let alone in association with flamenco music. In the fifteen years he spent in Spain, the cajón was never once mentioned (ibid., p.41). “I was told many times during my research in Lima that all modern Afro-Peruvian music was invented in the 1960s, based on Cuban and Brazilian models, and therefore had nothing to do with ‘authentic’ black culture in Peru” (Feldman, 2008, p.10). International claims of patrimony of the instrument quickly followed. The cajón was on the verge of being appropriated by international players.

Recuperation and full-fledged revival of the cajón

An international battle ensued, of which cajón was the protagonist. “. . . Black artists and musicians took up the torch, and a fully-fledged revival of Afro-Peruvian music took place in the 1960s”. The Afro-Peruvian makers reclaimed the cajón as their own.

On the second day of August in the year 2001, history came a full circle. The cajón was recognised as the Cultural Heritage of the Nation (Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación) by Peru. In recognising the cajón as national heritage, for the very first time in history, its makers too were able to forge for themselves a national identity. Later in 2014, the cajón was bestowed with the title of Instrument of Peru for the Americas (Instrumento del Perú para las Américas) by the Organization of American States (OEA). History pivoted very many years ago and culminated in this moment in time when the identity of the cajón and its maker were established in all of the Americas. Yet, there is a question which remains to be asked. Are the revival and recuperation truly complete without the inclusion of the prefix “afro” in the identity of the cajón?

Adapting to an inherently disadvantageous socio-political position, the ingenious invention of the cajón was a creative culmination of the restrictions imposed upon its maker. The atypical conditions of which the cajón is a product, were the catalysts without which the necessity of the creation of a substitute would never have been felt. The cajón wouldn’t have been invented if it weren’t for the African slaves living under the precise conditions in which they found themselves. This invention embraced the inventor´s past and present alike. The story of the cajón is the story of its maker, the Afro-Peruvian community and race, who trace their collective history, culture and identity back to this humble instrument.

References

De cajón Caitro Soto: El duende en la música afroperuana. Servicios Especiales de Edición S.A., 1995.

Del Busto Duthurburu, José Antonio. Breve historia de los negros del Perú. Fondo editorial del Congreso del Perú, 2014.

Feldman, Heidi Carolyn. Black Rhythms of Peru: Reviving African Musical Heritage in the Black Pacific, Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Mayorga Balcazar, Lilia, y Margarita Ramírez Mazzetti, editoras. Presencia y persistencia: Paradigmas culturales de los Afrodescendientes. Centro de Desarrollo Étnico-CEDET, 2013

Nayar, Pramod K. Postcolonial Literature: An Introduction. Pearson India. Kindle, Locations 1593-1596.

Rocca Torres, Luis. Herencia de esclavos en el norte del Perú: (Cantares, danzas y música). Centro de Desarrollo Étnico-CEDET, 2010.

Santa Cruz, Rafael. El cajón Afroperuano. SantaCruz E.I.R.L. Ediciones, 2006

Author

I am an Indian who was born and brought up in New Delhi. I currently work and travel out of this city. Professionally, I look after the promotion of Peru as a tourist destination in India. Even though my career profile might not suggest it, I am a researcher at heart and have been studying the socio-cultural history of Latin American countries for all the years I have been working with Spanish as a language. I studied the role of the cajón as a subaltern voice of the Afro-Peruvian community for the thesis I submitted to attain a M.Phil degree recently. I hope to pursue a PhD. in this area in the coming years, but I am yet to find the right opportunity to embark on this journey.

I am an Indian who was born and brought up in New Delhi. I currently work and travel out of this city. Professionally, I look after the promotion of Peru as a tourist destination in India. Even though my career profile might not suggest it, I am a researcher at heart and have been studying the socio-cultural history of Latin American countries for all the years I have been working with Spanish as a language. I studied the role of the cajón as a subaltern voice of the Afro-Peruvian community for the thesis I submitted to attain a M.Phil degree recently. I hope to pursue a PhD. in this area in the coming years, but I am yet to find the right opportunity to embark on this journey.

✿