The aspect of storytelling is a universal experience — found in most cultures. It is also something that has existed since the dawn of humanity in various formats — from the cave paintings of primordial man, the scroll paintings, etchings and prints of medieval society to the comic book and movie of today’s world.

A precursor to the audio-visual and the comic book, the kaavad’s origins are lost in the fog of time. Although many kaavad makers claim it to have originated about four hundred years ago, no one seems to know how or why it started. Myths abound, such as that of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s ban, that, prevented Hindus from visiting the temple. This event seems to have spurred this craft as it brought the temple home instead.

One of the delightful aspects of Hinduism is that if one creates space, say inside the home, for a temple — that space then becomes sacred and can be used to worship in, like in a temple. This space can then later can be re-converted into another purpose.

The kaavad is a portable shrine made in the form a painted wooden box. It is an artform native to Bassi in the Chittor district of Rajasthan. Kaavads are made of wood from the Neem tree and were traditionally painted using natural dyes. Today, the traditional colours have been replaced by “poster paint”. The kaavad is made by the Kaavad makers who are essentially carpenters (Basayati suthars). Their customers are the storytellers (kaavadiya Bhats or Ravs) of Marwar.

As Nina Sabnani, a kaavad researcher and professor, observes, “Kaavad Banchana, an oral tradition of storytelling, is still alive in Rajasthan where stories from the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana are told along with stories from the Puranas, caste genealogies and stories from the folk tradition. The experience is audio-visual as the telling is accompanied by taking the listener on a visual journey made possible by the kaavad shrine. Against the backdrop of storytelling it invokes the notion of a sacred space and provides an identity to all concerned with its making, telling and listening.”

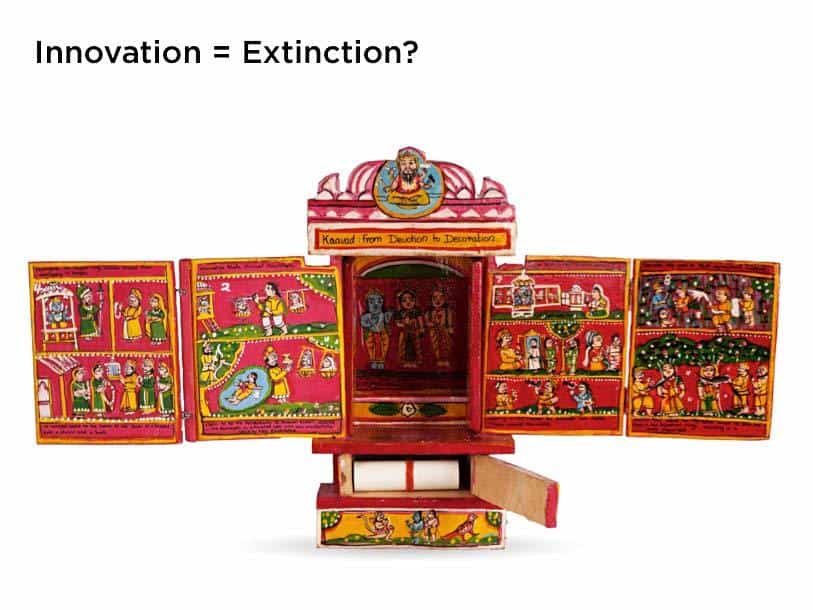

The architectural nature of the kaavad, which resembles both a cupboard and a temple, lends itself elegantly, to how the story unravels through its hinged doors… until the supreme lord is revealed in the inner sanctum (garba griha). The deities are usually Ram, Lakshman and Sita or Jagannatha, Balabhadra and Shubhadra.

The situation today

The kaavad tradition and craft is on the brink of extinction with less than ten practicing artisans making it and a handful of kaavadiya bhats who still recite stories from it. There has been a dramatic shift in the lifestyle and taste of Indians since “liberalization” of the economy and the country, which seems to be hooked on television, Bollywood films and social media, doesn’t seem to need the kaavad anymore. This has led to a further decline in the craft and the number of practitioners some of whom have resorted to making furniture in order to survive. Others have improvised to make a quick sale to tourists or to middle-men by producing smaller versions of the kaavad, where the narrative is no longer a story, but mere decoration. The goal is to make the kaavad enticing and yet cheaper than the original version by using less detailed paintings and bright colours. The traditional kaavad — popularly known as the Marwari kaavad—has ten doors, while the smaller kaavads have eight and sometimes even four doors.

While the traditional kaavads always had a red background, the new renditions come in all sorts of colours to attract the tourist’s eye. Additionally, artisans are improvising by creating kaavads with themes that are more broad and “modern”, such as kaavads with the English alphabet, the Crucifixion of Christ, or the Story of Moses, which is sold to local schools and to foreign tourists. Kaavads also address issues facing villages in India such as crop harvesting, irrigation and the use of pesticides. Many NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) have also commissioned kaavads to depict social or environmental issues that are then used as a training manual in villages and small towns.

As part of Sangam: the Australia India Design Platform, we created a series of kaavads which were given as gifts to the delegates at the Make in New Again conference at NID, Ahmedabad, India in 2012. These kaavads were developed in collaboration with Mangi Lal of Udaipur.

My chance meeting with Mangi Lal, like my chance meetings with many artisans, happened at one of the numerous craft melas and bazaars in the capital. However, I didn’t meet Mangi Lal in Delhi, I met him at a craft fair in Udaipur, where I was taken by the large kaavad he and his family had made. Once we made this connection, he visited my studio around the time of this project. As with many artisans in India, Mangi Lal was looking for work, but he initially got overwhelmed when we mentioned that we had a large order to give him, since he was used to making one or two at a time. It didn’t help that we also didn’t want the “usual story” but that we were keen that he narrates the story of his craft and artisans like him through the medium of the kaavad.

We thus used the vehicle of the kaavad itself to tell its own story, which, one fears, might be the last meaningful and contemporary story it might ever tell. The idea to create such a series of kaavads was to raise pertinent questions about the kaavad and crafts in general.

What happens when a craft innovates so much that it loses its initial purpose? If the artisans gain livelihood at the cost of the craft, how does that change things for the craft or the way it is perceived? Does that matter or does just the survival of skilled artisans is what matters in the end? What happens when a craft based on storytelling has no audience to tell those stories or audiences who are not educated enough to understand those stories?

The kaavad, much like a lot of other Indian crafts, found patronage during the age of the maharajas in India. Since independence, these traditional patrons of crafts are no longer able to patronise and support crafts like the kaavad. In such a situation, both Indian and foreign tourists unwittingly become the patron of these crafts. But unlike the maharajas, these new patrons are not as savvy about the history, the context and the meaning of these crafts.

Mangi Lal laments that most customers today are not aware of the tradition of the kaavad and the stories recited by kaavadiya bhats (the customers of the kaavad makers) who could tailor the story according to each of the patrons according to their family history and context. Without the bhats, the kaavad becomes a “display piece”, another decorative item, whose owner lacks the knowledge or sensitivity to treat it as a devotional object, which is to be viewed (darshan) and venerated daily as a temple of the Gods, and, appreciated as a unique work of art.

Crafts in India, never tell the story of its own plight — but instead their beauty and intricacy tends to belie the real state of the craft. We decided that it was time that artisans should tell their own story — of themselves — and their craft in general — via the very medium of the kaavad. For Sangam 2012, we used the kaavad to tell its own story, which sadly might be the last story it would ever tell.

What is the value of a “wooden box”, despite the vivid colours and detailed illustrations — without one knowing the context and the intricacies of the stories being portrayed?

We decided to give captions in English since most of the patronage comes through English speaking tourists who tend to be unaware about the rich history of this beautiful craft as well as the stories they showcase. In this way, the voice of the bhat is replaced by the English captions, which work as subtitles.

The doors on the left of the kaavad, trace the history of the origin of the kaavad which are essentially based on a few different myths. The right side panels look at the contemporary use of the kaavad such as in teaching about various issues related to agriculture; empowerment and education of women; the protection of the environment etc. As always, the Gods can be viewed inside the sanctum of the shrine. In this case, we had the artisans paint themselves making the kaavad on the reverse side. In this way, we try to tell the story of a craft and its people through the very medium they create on a daily basis as a part of their place in the strata of Indian society.

The kaavad as a craft might fade away, but the art of the kaavad is undergoing a resurgence in some ways as some of the few artisans, such as Satyanarayan Suthar, are becoming artists and mainstream artists such as Gulam Mohammed Sheikh have been using the kaavad in new and innovative ways in his art.

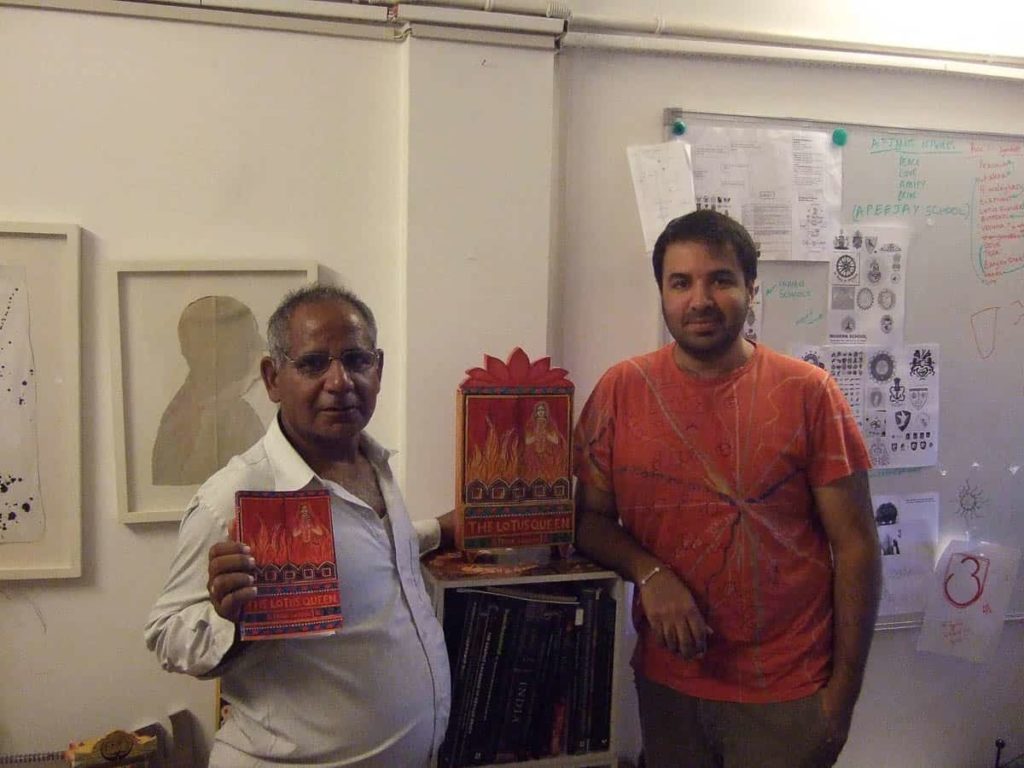

- Cover based on design by kaavad maker Dwarka Prasad

- Look who walked into Ishan Khosla Studio today. Dwarka Prasad from Bassi, Rajisthan, the Kaavad painter who made the work on the cover of The Lotus Queen

Links

- The Story of the Kaavad

- The Lotus Queen (Book Cover)

- Kaavad: Travelling Shrine, Home by Gulammohammed Sheikh

- The Kaavad storytelling tradition of Rajasthan by Nina Sabnani (pdf)

- Nina Sabnani bibliography

Author

Ishan Khosla is a designer, teacher and artist currently living in New Delhi, India, where he runs Ishan Khosla Design — a studio that is in its ninth year of existence which is interested in people, communities, exchange, internationalism, India, anthropology, rural livelihood, sustainability, craft and design. IKD is currently planning to develop an app and game for children based on a traditional Indian tribal art. They have recently developed the first digital typeface based on Godna, or tattoo art from rural Chattisgarh, designed in collaboration with three tribal women from the marginalised tattoo art community in the Gond tribe of central India. This typeface will be for sale at US$ 30 on the website. Money collected from the sale of this typeface will be used to fund more such projects with other marginalised communities practicing craft or tribal art in India. Godna Typecraft along with Chittara Typecraft will be a part of an exhibition at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in February 2017. These initiatives began as a result of the creation of the Sangam (the Australia-India Design Platform) identity in 2011. Lastly, IKD is currently working with Australian artist, Mandy Ridley, and two Mithila artists, Pushpa and Pradyumna, in developing an artwork for the Kochi Biennale, in December in Kochi, India.

Ishan Khosla is a designer, teacher and artist currently living in New Delhi, India, where he runs Ishan Khosla Design — a studio that is in its ninth year of existence which is interested in people, communities, exchange, internationalism, India, anthropology, rural livelihood, sustainability, craft and design. IKD is currently planning to develop an app and game for children based on a traditional Indian tribal art. They have recently developed the first digital typeface based on Godna, or tattoo art from rural Chattisgarh, designed in collaboration with three tribal women from the marginalised tattoo art community in the Gond tribe of central India. This typeface will be for sale at US$ 30 on the website. Money collected from the sale of this typeface will be used to fund more such projects with other marginalised communities practicing craft or tribal art in India. Godna Typecraft along with Chittara Typecraft will be a part of an exhibition at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in February 2017. These initiatives began as a result of the creation of the Sangam (the Australia-India Design Platform) identity in 2011. Lastly, IKD is currently working with Australian artist, Mandy Ridley, and two Mithila artists, Pushpa and Pradyumna, in developing an artwork for the Kochi Biennale, in December in Kochi, India.