For many years Shanghai has acted as a port or gateway for foreigners into China. It is a city with a fragmented identity, which is always changing and comprises of the old and the new, modern and traditional, Eastern and Western. It is in this city where I first found myself immersed in Chinese culture back in 2014. I moved from South Africa to China to teach English and later got the opportunity to return to jewellery through a three-month residency at San W Gallery/ Studio, Shanghai.

It was in the contrasts of Shanghai, particularly in the juxtaposed woven bamboo fences and modern concrete walls of the Former French Concession neighbourhood, where I found my inspiration for my residency. I have always been fascinated by the rustic aesthetic of these woven bamboo fences, and I tried to replicate it by cutting up copper sheets and weaving it diagonally as seen in Interlace Neckpiece. From this starting point, my attention was drawn to other woven products that I saw around me such as baskets, fans and woven chairs. My research subsequently expanded to weaving techniques from other countries as I realised that weaving, in its various forms and materials, is visible in most cultures around the world.

Gussie van der Merwe, Hong Bao, 2017, Copper and imitation gold leaf, 20 x 21 x 4 cm, photo: Gussie van der Merwe

The piece Hóngbāo is an envelope-shaped vessel. This piece was created by placing gold leaf on copper sheets in the shape of ancient Chinese coins with Chinese characters. The copper was then cut into strips and woven into a vessel. The lid has been completed, but the other side has been left undone with the metal strips going in all directions. During Lunar New Year celebrations, friends and family exchange red envelopes containing money. These red envelopes are known as 紅包, hóngbāo. The value of these envelopes is not just in their physical contents, but rather in the good wishes written on the envelope and wishes conveyed through the act of giving the envelope. The piece Hóngbāo illustrates how individuals are woven together into a community through the ritual of gift giving. Although gift giving can be seen in most, if not all, cultures around the world, the finer nuances of a gift economy are extremely complex. The meaning of a gift and the obligatory reciprocity differs for different people depending on their religious and cultural background. As an outsider viewing these rituals, one can never quite grasp the emotional en sentimental bonds formed by these gifts.

I find inspiration in these cultural nuances and through it, my work becomes a manifestation of living as an expat in China, my travels to other countries as well as my South African heritage. As a Caucasian Afrikaner born in South Africa, a by-product of European colonialism, my background is a hybrid of cultural experiences woven together. Through my work, I explore the cultural effects of an increasingly globalized world has on the individual and in the process weaving together a new cultural identity—that of a global citizen.

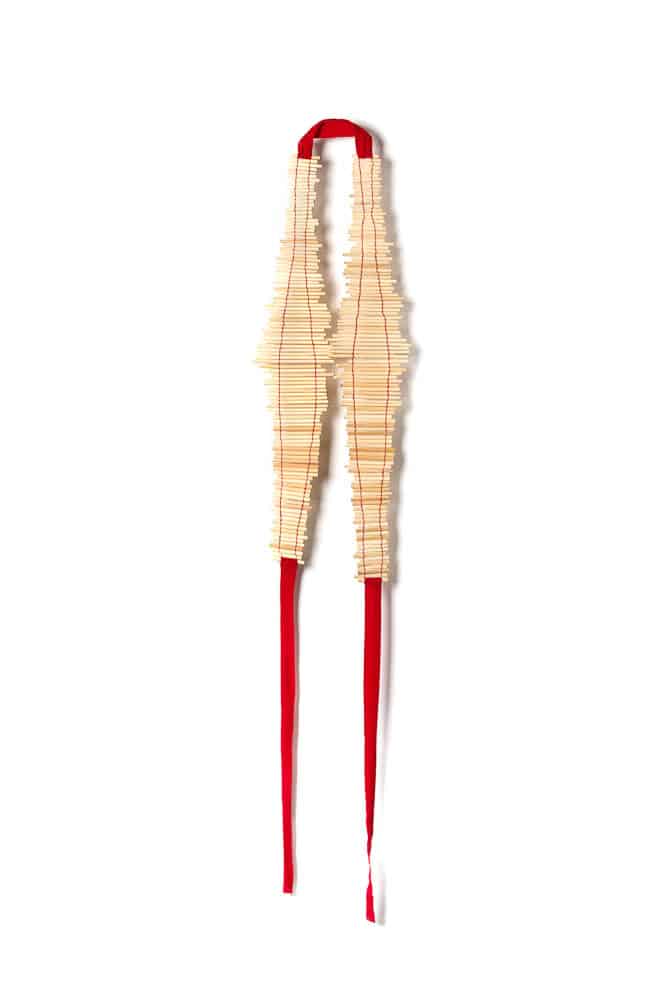

Lavinia Rossetti, Food Safe Neighbour Sharing, 2017, Bamboo chopsticks and silk, 170 x 30 x 1 cm, photo: Zoe Zeng

While I was completing my residency at San W Gallery/Studio, an Italian jewellery artist, Lavinia Rossetti, was doing the same. The results of her residency concluded in a body of work titled: Food Safe Neighbour Sharing. The words for Rossetti’s title were borrowed from Chinese characters printed on take-away chopstick packaging. It is a direct translation of the characters printed on its packaging. This direct translation is typically mismatched, almost comically incomprehensible and not dissimilar to translations commonly seen in Chinese restaurants, in China and abroad.

In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, In 在之间 Between, which exhibited the results of our residencies, Rossetti stated, “Eating is one of the natural ways to explore a new country. After arriving in China chopsticks were the first ‘tool’ of mediation between me and a new reality. These utensils became my keys for new flavours and for a new culture.”

Rossetti’s pieces, in Food Safe Neighbour Sharing, are made from bamboo chopsticks and silk fabric—two materials associated with China and Chinese culture. The structure of her pieces draws inspiration from traditional Chinese garments. Rossetti goes on saying, “I am fascinated by the symbolic meaning as well as the aesthetic and intrinsic qualities of chopsticks. By cutting up, interlacing and imprinting them, I transformed one of the most common objects used, to create structures that became wearable pieces inspired by my new surroundings. The work is my intuitive analysis of China and its flavours, a very fast digestion of all the visual inputs that I got during this stay.”

By repurposing everyday objects, which were meant for one-time-use, Rossetti makes a statement about today’s over-consumption. “This body of work consists of 157 pairs of disposable chopsticks. I collected the chopsticks that came with every takeaway meal and asked the staff of the gallery to use chopsticks which were made to be washed and reused after meals.” Through Rossetti’s work, we are compelled to consider what impact our decisions have on our environment. We begin to question the manner in which we consume and waste.

Moniek Schrijer, Add to Cart, necklace, 2017, chromed steel shopping carts, sterling silver, lemon quartz, 13 x 24 x 36 cm, photo: Moniek Schrijer

During the same time Rossetti and I were completing a residency in Shanghai, New Zealand jeweller, Moniek Schrijer undertook a residency at the Chinese European Art Centre in Xiamen, China. While visiting Shanghai, Schijer met up with us and shared her experience. The results of Schrijer’s residency were thought-provoking, with references taken from her new surroundings. Her work is a perfect balance between seemingly effortless execution and careful consideration of concept. Schrijer’s pieces made during her residency act as a commentary on China’s past, present and future. She employs ready-mades in her work, objects that had a life with a different use before, to make new objects with added significance. Thus, the old function is in constant dialogue with its new function as a wearable object.

Schrijer’s Add to Cart is a neckpiece constructed from silver and miniature chrome-plated steel shopping carts. This piece can be interpreted as a comment on China’s growing economy and its ensuing focus on consumption as the means to drive its expanding economy. China’s economy in the twentieth century was primarily centred on manufacturing and industry. Today, however, China has ambitions to become an economy driven by consumption. China is rapidly expanding its middle class, moving away from its reliance on manufacturing cheap exports. Chinese online shopping platforms like Taobao.com and JD.com make up two of the largest online shopping platforms in the world. Ironically, Schrijer constructed the piece mostly out of ready-mades, objects most likely purchased from these online shopping platforms either by herself or the retailing middleman.

Moniek Schrijer, Bone China Pendant Series, series of 4, 2017, bone silk paint, bones, porcelain paint, cotton cord. , 35 x 19 x 3cm excluding cord (sizes vary), Moniek Schrijer

In her Bone China Pendant Series, Schrijer uses a play on words in the title of the series. Bone China may refer to China’s iconic blue and white ceramics, once one of China’s greatest exports to Europe. Bone China may also refer to the material used to make these blue and white pendants—bone found in China. These pendants are ritualistic and superstitious looking, much like the many bone artefacts excavated in China and referred to as oracle bones. With this intertextual reference, one cannot help to think what Schijer’s bone pendants predict for the future.

Throughout history, currency has taken different forms, from shells and bones to metal coins and paper money. Today, currency as a store of value continues its evolution. As currency continues to evolve, we enter the new age of cryptocurrency with Bitcoin and Etherium leading the race—although countless others are hastily joining the fray. With these cryptocurrencies, geographical borders are being shifted and the future of currency in its current form is ever more uncertain. Schijer’s piece Memory Coin Pendant takes on the shape of an ancient Chinese coin, but it is made from computer hardware. This piece could be seen as a comment on the intangibility of the virtual and the instability of value and wealth, which was once more tangible, more predictable. In ancient China, as in many other civilizations around the world, coins were strung and carried on the body for safekeeping, much as adornment would be worn. In this same way, Schrijer’s Money Coin is a physical object that represents wealth and adorned around the neck. However, this piece alludes to the virtual value coded and established in a simulated, computer-generated sphere.

In view of the jewellery by Rossetti, Schrijer and myself, it becomes clear that immersion in new or shifting cultures can stimulate artistic enquiry. When immersed in a new place, in a culture different from one’s own, one’s senses heighten. One starts noticing details that would otherwise and subconsciously, pass one by. In addition, time, as in place, can shift perspectives. This inevitably stimulates enquiry into our current, modern culture.

The works discussed above reflect on China and its ever-evolving culture within a global context. For in fact, in post-modern philosophy, we know that identities and cultures are not stable. They are in a constant state of flux and in dialogue with the past, present and future. This idea of a country or culture having a fragmented and continuously changing identity can best be illustrated through this quote of French writer, Pierre Daninos, in his book Major Thompson, “The only people who claim to know such a country inside and out are those who have crossed it in two weeks and left with a ready-made opinion unopened in their suitcase. Those who live there learn each day that they know nothing about it, except perhaps the opposite of what they knew…”.

It is through our art that we may mirror our personal and cultural identities, our hybrid mismatches and innovative global references. These new constructions we compose, and at times presumptuous interpretations we make thereof, then create an intensely dynamic global playing field. Through the work of Rossetti, Schrijer and myself we set forth a breeding ground for cultural understanding. Art jewellery, like the pieces discussed here, serves to incubate an empathetic and understanding space, which one could argue is very much needed in a time where interactions are complicated due to the negotiations of culture and globalisation.

Artist

Gussie van der Merwe is a South African artist whose work roams the intersection of art, craft, and design. She holds an MA in Visual Arts, titled Relational Aesthetics and Deconstruction of Jewellery: A Practice-led Inquiry, as well as a BA in Creative Jewellery Design and Metal Techniques from Stellenbosch University, South Africa. During her master’s degree, she attended a semester exchange the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, which was instrumental in her understanding of contemporary jewellery and art. Currently, Gussie is living Shanghai, drawing inspiration from Chinese culture and living life as an expat.

Gussie van der Merwe is a South African artist whose work roams the intersection of art, craft, and design. She holds an MA in Visual Arts, titled Relational Aesthetics and Deconstruction of Jewellery: A Practice-led Inquiry, as well as a BA in Creative Jewellery Design and Metal Techniques from Stellenbosch University, South Africa. During her master’s degree, she attended a semester exchange the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, which was instrumental in her understanding of contemporary jewellery and art. Currently, Gussie is living Shanghai, drawing inspiration from Chinese culture and living life as an expat.