Artisans visit the Museum of Natural History

Artesanías de Chile invited Mapuche weavers to the Museum of Natural History, where they studied ancient textiles that they would re-create back home.

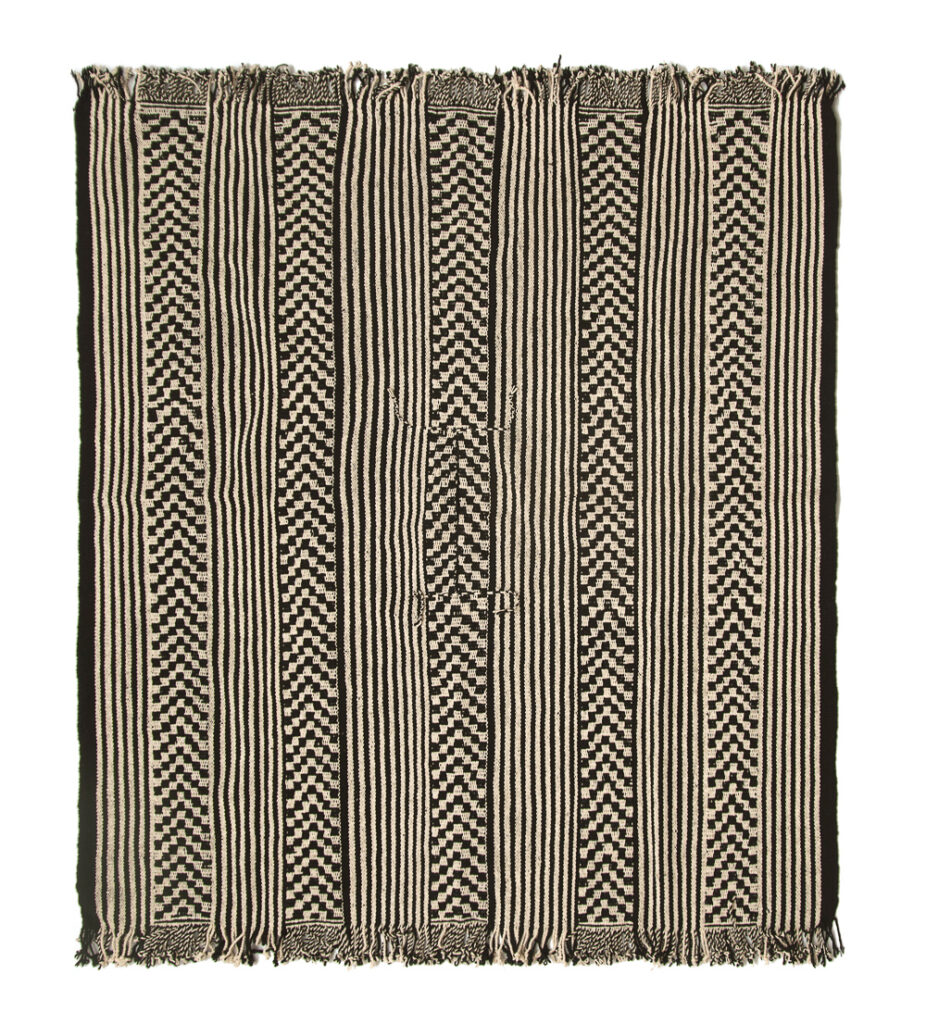

200 unknown Mapuche blankets and sashes were woven two centuries ago, stored in a Chilean museum. A foundation that preserves traditional crafts then finds out about its existence. 17 Mapuche weavers travel 600 kilometres to meet them for the first time. This is a story about that day in a room, about the inspiration back in their workshops, about the memories that journey awakened, about the new collection that was born inspired by those pieces. It’s a story about the patrimonial rescue behind Herederas de Llalliñ.

✿

One of the pages of the book Herederas de Llalliñ, published in 2019 by the Artesanías de Chile foundation (available for free online) tells this story: when the Mapuche artisan Norma Calvulaf was a child, her grandmother used to encourage her to grab the cobwebs from the trees that, in the light of dawn, laden with dew, seemed silver.

- Eliana Tralma

- Claudia Silva

- Marcela Llanquileo

- Angela Calfulaf

- Angela Llanquinao

“She told us to rub our hands with them and burst the spiders in order to get their weaving talent out of them and keep that gift between our fingers,” she recalls in the book. At 7, Norma already knew how to spin.

“At that time we always walked into the fields with my brothers, taking care of the pigs. We knew that when we found an empty bird’s nest we had to bring it back home running, where my mother burned it and painted my hands with the ashes to convey her knowledge to me. Birds also have weaving talent, it is a matter of seeing how they build their nests”, adds Norma.

Her mother did it, she says in the story, because she wanted her daughter to be as good a weaver as her and as her ancestors. And Norma assures she succeeded. “My work is good, I have always been praised for it. My hands and my head are used to doing it. I only get the design. I have everything clear in my mind”.

Norma, one of the 17 Mapuche artisans whose story is outlined in the book, today is 47 years old and is considered by her community as a düwekafe, an expert weaver, heir to the knowledge of the llalliñ, of spiders.

In Mapudungun (Mapuche language) there are specific words for those who master this talent. For example, llallíñkushe means “old-primal spider”. She is the great ancient and original weaver, who, like wise weavers, also knows how to spin. She is the one who “helps” the girl: the llalliñ or little spider, who’s learning to weave. Inoffensive, a llalliñ in the Mapuche cosmogony is that spider that inhabits the domestic, without poisoning or stinging, but gives itself to collaborate and share its knowledge.

Their language has these words because weaving has been its millenary form of communication, where Mapuche, like so many other indigenous around the world, collect the cosmogony of their people. That’s why it’s said that the makuñ, blankets dressed by Mapuche men, and the trariwe, girdles wear by women, are the books of this culture. Texts were written in a language that nowadays few düwekafe can “write”. Few, because those who dominate the textile technique are women: expert weavers who skillfully reproduce the ancestral iconography of their people, but who, with the arrival of the modern world and in the desire to simplify steps, innovate or commercialize, have vanished their meaning.

The same has happened with the ability to shear, wash, carve, spin, twist, dye, tie, weave on the witral or Mapuche loom. One of the most deeply-rooted Mapuche weaving techniques, weaving with ñimin, is still alive where Norma lives, in Padre Las Casas, and also in another rural nearby village, Cholchol. Many of Norma’s acquaintances live there, also heiresses of llalliñ, who still weave trarikan makuñ, kind of blanket that only can be dressed by the community leaders.

Surprise at the museum

- Artisans visit the Museum of Natural History

- Artisans visit the Museum of Natural History

- Artisans visit the Museum of Natural History

In early 2019, Norma received a phone call. She was contacted by Artesanías de Chile, a very well-known and recognised foundation with which she has worked for years, where she sells some of her pieces. The call came from someone located at their central office, 650 km north of Norma’s village, 12 hours afar from home, in Santiago, the capital city.

They wanted to ask her if she was interested in participating in a project of heritage rescue of old blankets and girdles that had been sleeping for dozens of years in the deposits of the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (Chilean National Museum of Natural History), one of the most important in Latin America, as well as one of the oldest of the world in its kind.

More than 200 trarikan makuñ and trariwe were woven by düwekafe centuries ago and of which Norma knew nothing. Neither did Luisa, Aurora, Marta, Claudia, Anita, Ángela, Audolina, Beatriz, Adela, Eliana, Juanita, Marcela, Jacqueline, Magaly, her neighbours and textile partners, weavers as her, in Padre Las Casas and Cholchol.

All were contacted by the foundation. The invitation was to travel to Santiago and visit the museum to see, touch and hold with their hands those pieces woven by Mapuche, their ancestors, more than a century ago. And, based on that experience, they were invited to create a new collection on their looms, which would honour that past by rescuing the complex techniques of fabric and colors that their ancestors achieved. They all said yes.

“The mission of our foundation is to protect and enhance the value of traditional, ancestral crafts, of trades that have been transmitted generation to generation within our territory and of which Mapuche textiles is a manifestation that is still alive”, explains Claudia Hurtado, executive director of Artesanías de Chile. “But if we don’t take care of that inheritance, it won’t last forever. Hence, we embarked on this rescue project, because it’s not only a matter of guarding the Mapuche heritage of immeasurable value, but also of encouraging artisans to want to keep it alive, which is not easy, because in Chile it still exists ignorance and little appreciation of traditional crafts and their creators”.

The bus with the 17 Mapuche weavers travelled all night from Cholchol and Padre Las Casas to Santiago. It was May 2019. A picture records their arrival at the museum, located in the huge Quinta Normal Park. Other images immortalise that journey that happened in that room located on the fourth floor of the museum, where, wearing rubber gloves so as not to damage the so-called “wool jewels” in the least, Mapuche weavers were able to see face to face and touch the past. The wealth of centuries captured in a textile piece. With their cell phones, and with obvious respect and emotion, they searched the collection.

Miguel Ángel Azócar, an anthropologist at the museum, also accompanied them that day. In the book that summarizes the history of this rescue, he details some of the pieces that were part of that encounter. “There were textile works from the beginning of the nineteenth century, such as a girdle or strap that traditionally used to be passed under the belly of the horse, but with anthropomorphic motifs, combined with leather, which is the oldest piece in the collection. A very rare and original equine implement ”, he says.

- Marta Canio

- Angela Calfulaf

“The artisans were impressed by the fineness of the fabric and the elaborateness of the design. You have to think that these ladies (their ancestors) drew with their heads what they wove, without a pattern, without a pattern. And they did it with perfect symmetry. The treatment they gave to the fabrics was exciting. Their respect and admiration. It was very important they could access this heritage, because they are the ones who can understand it the most and best”. Before the day was out, each weaver chose a piece to inspire them back in their workshop.

After the visit, the artisans returned to La Araucanía. Sitting at their loom back home, each one gave free rein to her creativity. From that visit, 10 trariwes and 12 trarikan makuñ were born. The collection was launched at the MNHN, an occasion where the pieces that inspired the artisans were exhibited together with those created in their honour. The entire process was recorded in a book called Herederas de Llalliñ, which also includes the stories of the artisans who participated in the rescue. The PDF version can be downloaded for free from the internet.

- Museum piece

- Jacqueline Tralma

But, what memories do the artisans keep from that day at the museum? One of them shares it with special precision in the book: the young and respected machi (medicine woman) of Ancapulli community, Eliana Tralma Colipi (42), to whom the relmu, the rainbow, appeared that day at the museum. “It jumped like a spark and everything was filled with colour: blue, red, pink, green, which contrasts with the remedies that I work, and yellow, which is characteristic of the Mapuche flag. It was the rainbow, the complete relmu, that appeared itself to me. And that gave me the sense to recreate the work of the old blanket that I chose in the Natural History Museum of Santiago with all this colour that you see”.

- Museum piece

- Aurora Huenchuñir

That which “can be seen” is a trarikan makuñ, a cacique blanket, chromatically bold and technically perfect. “The museum blanket attracted me, but I decided to varied the colors. The old one had no yellow. Neither blue. It had pale pink and aqua green. I felt it was my duty to elevate them, give them life again, because I felt sad they were so dull. And there the spark jumped”.

- Museum piece

- Ana Mena

Author

I’m a Chilean journalist, passionate about writing stories, especially from common but special people’s lives. Nowadays those stories are mainly about artisans. I worked for 12 years writing stories for a Chilean magazine called Paula, where I learned my trade, and since three years ago I put my knowledge and passion in the leading communication area of Artesanías de Chile Foundation. I also love to teach and work as a writing professor at the Communication Faculty at Universidad Católica de Chile.

I’m a Chilean journalist, passionate about writing stories, especially from common but special people’s lives. Nowadays those stories are mainly about artisans. I worked for 12 years writing stories for a Chilean magazine called Paula, where I learned my trade, and since three years ago I put my knowledge and passion in the leading communication area of Artesanías de Chile Foundation. I also love to teach and work as a writing professor at the Communication Faculty at Universidad Católica de Chile.