Eleni Gouga sought to revive the heirloom black woollen skirts of northern Greece, which then became a satchel for traditional bread.

(A message to the reader.)

Crafts that are enmeshed within our everyday lives become fine-tuned over time, transferred from generation to generation within close family circles and local communities. In Greece, this may involve learning to layer a perfectly crispy baklava, weave a light and sturdy basket out of local plants, or crochet a window cover so that just the right amount of daylight enters the bedroom in the morning. Often a grandparent will offer to teach these quotidian crafts to the next generation, but children and young adults may not recognize their value at the time that the offer is made, dismissing them as “old fashioned” or merely “nostalgic.” Their laborious methods or formal qualities may appear out of sync with contemporary consumer lifestyles, technologies, or aesthetic tastes. In such cases, the inter-generational “craft chain” of cultural inheritance becomes broken—but occasionally obdurate memories of these domestic practices persist through family anecdotes and heirloom objects, surfacing for revaluation by a new generation.

Unfortunately, renewed interest in these crafts may come too late to learn directly from the person with the “know-how.” In such cases, how does one attempt to access those once ubiquitous skills? Can a near-extinct cultural practice be reinstituted by closely observing and researching a moot craft object that has been left behind by its original maker? Can craft techniques or sensibilities be reclaimed through a reverse-engineering process, and, perhaps most importantly, can they be transformed so their results are valuable within a contemporary context?

“The secret lies in the way you knead.”

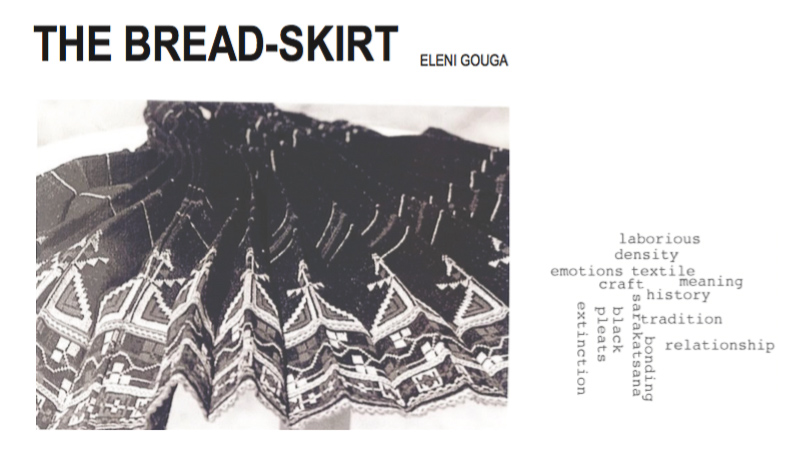

In 2016, a young designer named Eleni Gouga grappled with these questions in her Bread-skirt project. In response to a brief given in a graduate Post-Industrial Design seminar at the University of Thessaly, she set out to critically examine how “prika” (προίκα)—the Greek dowry tradition of family inheritance—operated within her personal life, at a time when global migrations were increasingly the norm. Recently, she had inherited a lavishly embroidered, densely pleated black woollen skirt –an heirloom crafted and worn in the 1930s by her maternal great grandmother. The rugged yet elegant skirt was worthy of a folk art museum’s collection. It embodied her family’s cultural heritage as ethnic Sarakatsani, a nomadic people who lived as shepherds and goat herders in the mountains of northern Greece for hundreds if not thousands of years.

Like many Sarakatsani, Gouga’s family abandoned their transhumant, rustic lifestyle following the two World Wars, opting instead for economic opportunities afforded by settling in nearby urban centers like the city of Volos. The tangible and intangible links to Sarakatsani culture became less apparent as they assimilated into urban life, and material artifacts, like her great grandmother’s skirt, were hidden away in storage chests—signifiers of a distant past and foreign lifestyle.

Historically, Greek prika included money, property, and hand-crafted items (e.g., embroidered table linens, bedsheets, clothing items, curtains, woven rugs, etc.) that a bride’s family gave to the husband at the time of her marriage, often stipulated in a written contract. For centuries, part of the prika was made by local women in the bride’s immediate community. Often a young girl participated in co-creating her own dowry, learning craft skills through rituals of collective making and exchange that took place throughout her childhood and teenage years, often in the context of her family’s home. By the time Greece entered the European Union in the early 1980s, the government outlawed the prika as a social institution. Increasingly, the hand-crafting of domestic objects became more rare, with the next “European” generation of Greeks opting to purchase readymades in a globalized marketplace.

In an earlier era, Gouga’s prika would have been reserved for her presumed wedding day, but her maternal grandmother gifted the Sarakatsani treasure to Eleni to encourage her professional aspirations as an emerging designer. Mesmerized by the intricate and sturdy pleating of her great grandmother’s woollen skirt, she inquired about how to craft a textile item like this. She soon learned that her great grandmother died tragically just three days after giving birth, so the intangible craft skills of garment design typically transferred between generations were now absent from their collective memory. Neither Eleni, her mother, nor her grandmother knew how to fabricate woollen pleats. They no longer had people in their immediate urban community who harbored that knowledge. The three remaining generations of women took this fractured cultural condition as their challenge: to collectively recover the technique through a series of hands-on trials and errors.

Rather than attempting to weave the woollen fabric, they chose to replicate the most characteristic aspect of the skirt: its unique form of pleating. The structure appeared very simple, with three layers of black fabric pleated and sewn on a textile belt. But they soon discovered that the deciding factor of properly fabricating the garment is lodged within the pleating process itself: they must ensure their pleats remained rigid while the skirt was being worn. At first, they tried stiffening the pleats with a can of store-bought spray starch, but then realized this product was imported to Greece in the post-WWII period, and would not have been available during Eleni’s great grandmother’s lifetime. They then tested other common materials to mimic spray starch, realizing that flour and water, an old-fashioned hot iron—warmed over a fire—and greaseproof paper could combine to produce the desired effects. These simple substances and domestic objects were likely the same materials available to the nomadic Sarakastani in earlier eras.

While making the fabric starch out of flour and water, Gouga was struck by how these simple kitchen materials were also the basic ingredients of the family’s bread, hand-crafted daily by her grandmother. The women discussed how much the smell of bread baking permeated Eleni’s childhood memories, and her grandmother shared stories about baking since she was 8 years old, having learned from the women in her community who substituted for her absent mother. This conversation sparked the awareness of another potential rupture in their family’s cultural heritage and collective memory: Eleni had never learned how to bake bread. Her grandmother insisted this be remedied at once: “The secret lies in the way you knead.” They marvelled over how the success of crafting both the bread and the heirloom garment involved a similar act of rhythmically folding a specific material back onto itself. Gouga began practicing breadmaking daily until her grandmother was satisfied with her technique, reflected in the flavor and texture of the bread.

This layered craft experience inspired Gouga to envision and design Bread-skirt: a black woollen bag, pleated and adorned with a simple hand-embroidered red line mimicking the Sarakatsani’s pleating pattern. Bread-skirt did not resemble the intricate embroidery of her inherited garment. Rather, she identified its vital elements and translated them into something new. This reinvented “skirt” covered the freshly baked bread she had learned to master. Its substantial woollen material insulated the loaf like a tea-cozy, echoing the way her great-grandmother’s skirt held in her body’s heat during the cold winter months in the mountains.

Paying homage to her family’s nomadic roots, Gouga decided that her Bread-skirt needed to be portable. Her design solution was to add a removable strap, converting the bag into a satchel. It could now be used to transport home-baked bread from her kitchen to her friends’ homes, regardless of where Gouga would need to reside throughout her lifetime. By transforming her prika, Eleni reaffirmed the Sarakatsani impulse to migrate in response to changing environmental or political conditions. Armed with a renewed knowledge of her matriarchal cultural lineage, Gouga now harbored its intangible craft skills within her own hands.

About Lydia Matthews and Evren Uzer

Lydia Matthews is an independent curator, writer, walking artist and Professor of Visual Culture at Parsons School of Design at The New School. Based in New York and Athens, her practice focuses on developing socially-engaged art projects in the US and abroad. Collaborating with visual artists, designers, artisans, musicians, dancers, multidisciplinary scholars, and local residents, her work addresses challenging aspects within people’s everyday lives. Currently she is curating a project for the 2021 Porto Photo Biennial with Susan Meiselas and Alfredo Jaar, focused on the impact of colonialism within the Black community in Porto and Angola. Also she is co-creating a multi-sensory, participatory walking performance at the Benaki Museum’s Patrick Leigh Fermor House in the southern Peloponnese, pairing members of the blind/ low-vision community with local high school students to explore aspects of the local environment that inspired Fermor, an avid walker and travel writer. Visit Travessia and lydiamatthews.com

Lydia Matthews is an independent curator, writer, walking artist and Professor of Visual Culture at Parsons School of Design at The New School. Based in New York and Athens, her practice focuses on developing socially-engaged art projects in the US and abroad. Collaborating with visual artists, designers, artisans, musicians, dancers, multidisciplinary scholars, and local residents, her work addresses challenging aspects within people’s everyday lives. Currently she is curating a project for the 2021 Porto Photo Biennial with Susan Meiselas and Alfredo Jaar, focused on the impact of colonialism within the Black community in Porto and Angola. Also she is co-creating a multi-sensory, participatory walking performance at the Benaki Museum’s Patrick Leigh Fermor House in the southern Peloponnese, pairing members of the blind/ low-vision community with local high school students to explore aspects of the local environment that inspired Fermor, an avid walker and travel writer. Visit Travessia and lydiamatthews.com

Evren Uzer is a NYC based educator, urban planner and community practitioner working on civic engagement in planning and design and her current research focuses on activism, critical heritage studies and feminist spatial practices. She is Assistant Professor of Urban Planning at Parsons School of Design at The New School and also holds a senior researcher position at School of Design and Crafts, University of Gothenburg in Sweden. She has an ongoing research project on “Manipulating Dissent: Exploration of activism in NYC” which explores activism and feminist spatial practices and “Community engagement” project which looks into ethical community academia partnerships in design education.

Evren Uzer is a NYC based educator, urban planner and community practitioner working on civic engagement in planning and design and her current research focuses on activism, critical heritage studies and feminist spatial practices. She is Assistant Professor of Urban Planning at Parsons School of Design at The New School and also holds a senior researcher position at School of Design and Crafts, University of Gothenburg in Sweden. She has an ongoing research project on “Manipulating Dissent: Exploration of activism in NYC” which explores activism and feminist spatial practices and “Community engagement” project which looks into ethical community academia partnerships in design education.

Comments

What is the importance of maintaining a “normal distribution of letters” in placeholder text like Lorem Ipsum? regards Kehidupan Kampus