Samuel Tupou, Live Forever (Time Machine), 2019–2022, arcade game cabinet, serigraph on perspex and board, LED lights, 140 x 60 x 56cm (left) and Low Resolution Dreamz, 2022, spray paint, serigraph and glitter on board, 200 x 300cm (right) photo: Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery.

Miranda Hine finds clarity in the tapa-inspired pixelated versions of precious family photographs.

My eyes adjust to the gallery walls around me as I come in from the street in Meanjin/Brisbane’s West End. Artist Samuel Tupou and his partner, Ania, are at the far end of the gallery placing tiles of coloured board next to each other on the wall. There’s clearly an order to how the tiles are going up, although I don’t see it. Ania is counting the tiles as she places them in rows on the table, and Samuel takes them one by one, adhering them to the wall. Each tile acts as a pixel in this 2 x 3 metre wall installation, Low Resolution Dreamz, which shares a name with this exhibition of Samuel’s recent work at Onespace Gallery.

As Samuel places more pixels on the wall, they build an expansive image, abstracted and hard to make out. One large figure in the foreground and two smaller ones behind. It’s based on a photograph taken earlier this year that Samuel tells me depicts Ania in front, holding the camera, and Samuel and their son in the background. Without knowing that story, I could stare at it for hours imagining who or what the figures are.

Samuel uses family photographs like this one, taken between the 1970s and 2022, as the starting point for the works in this exhibition. Using a digital process, he reduces each image to a maximum of 10 colours, transforming it into a series of low-fi pixels reminiscent of 8-bit images. He then paints these pixels onto canvas or board, or individual tiles in the case of the wall installation, before screen-printing a repeated black pattern over the top.

Samuel Tupou, Road Trip 1979, 2021, serigraph and acrylic on board, 120 x 180cm, photo: Josef Ruckli. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery.

Ten of these large works, as well as some small works on paper and one sculptural piece, make up the exhibition. Some works stand out immediately. Road Trip 1979 (2021), a 1.2 x 1.8 metre work on canvas, oozes warmth and light through its proliferation of orange-toned pixels. Three shapes, which I can quite confidently identify as people, emerge in purple and white. Samuel explains that the photo was taken when his grandparents came from Tonga to visit his family in the Northern Territory in 1979. The orange, he says, is drawn from the quality of the glary 1970s film photograph.

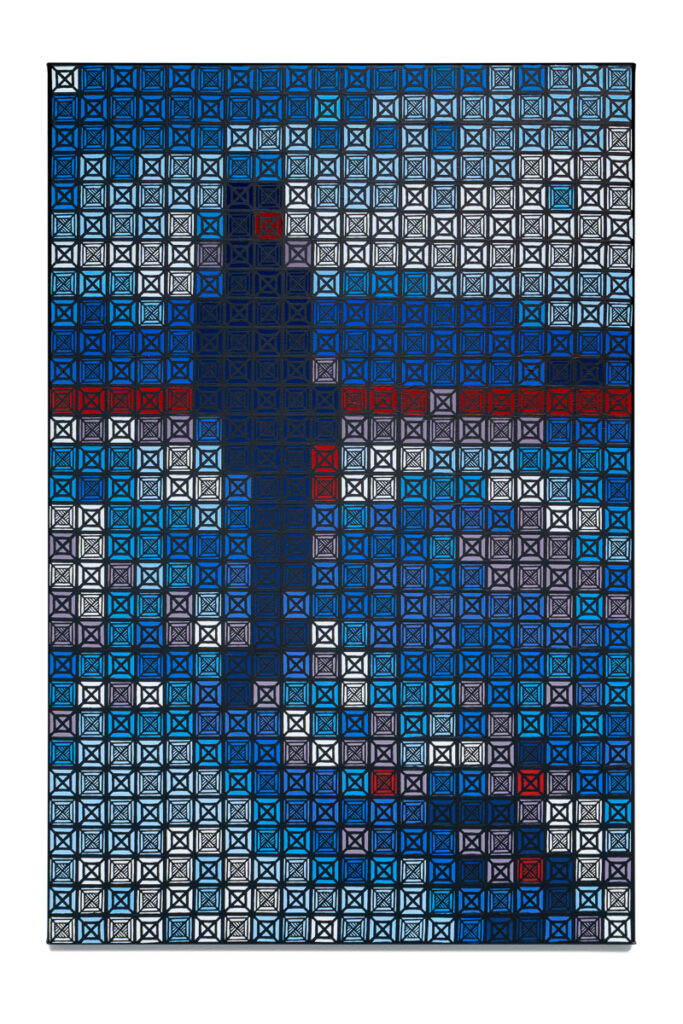

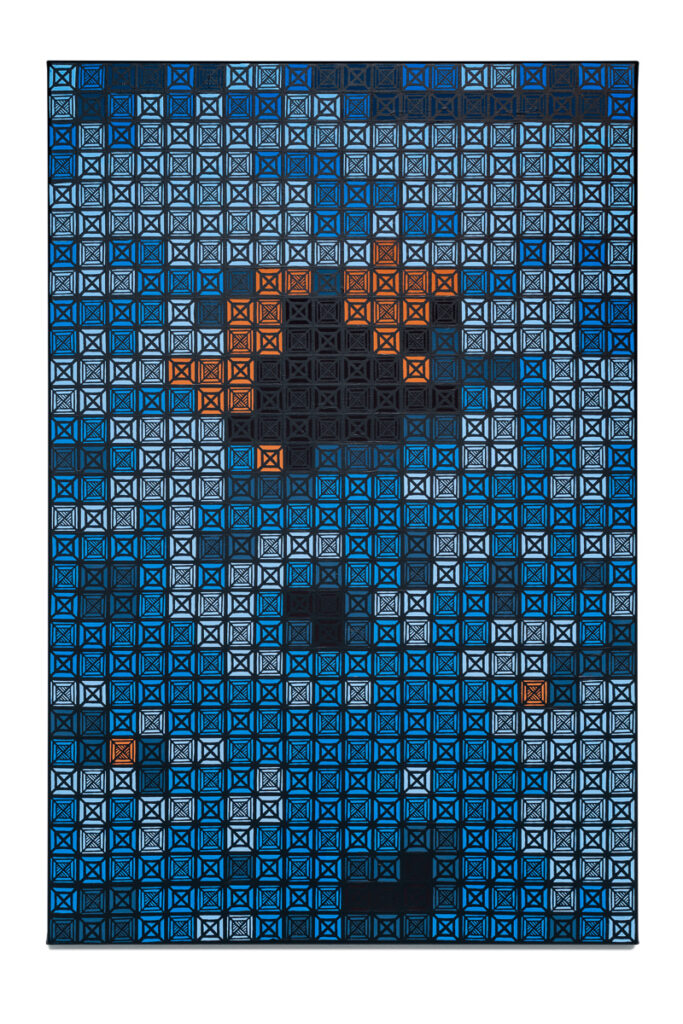

On the opposite wall, two mostly blue works evoke an entirely different time and place through colour alone. Mountain BBQ, Mt. Mogielica and Bałwan, Gliwice (2022) are based on photographs from a recent trip to Poland to visit Ania’s family. Informed by the winter landscape and the quality of high-resolution digital photographs, these works indicate a glistening of ice or snow, a low-set sky, a central figure and fire glow, and a coldness in complete opposition to the blistering heat of Road Trip 1979.

- Samuel Tupou, Mountain BBQ, Mt. Mogielica, 2022, serigraph and acrylic on canvas, 90 x 60cm, photo: Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery.

- Samuel Tupou, Bałwan, Gliwice, 2022, serigraph and acrylic on canvas, 90 x 60cm, photo: Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery.

With their nostalgic reference to 8-bit images and acknowledgement of changing photographic technologies, these works can be read as a reaction against current fast-paced digital image consumption. By their very nature, the works require you to slow down your process of looking, allowing the images to emerge in front of you. This is a familiar way of seeing for me. Because my eyesight is severely diminished, Samuel’s world of large, coloured planes and indistinct shapes is close to how I experience the world without glasses. Having spent all my life impatient with my blurred vision, I’ve recently discovered how beneficial it can be in my work as a painter, to be able to remove detail and see the bigger picture emerge. Samuel’s works are a similar revelation: simple combinations of colour and form create ambiguous images drenched in a specific time, place and atmosphere that you can’t quite put your finger on.

Unifying Samuel’s series of personal moments relies on another form of patterning beyond pixelation. Intricate black linework is screen-printed over the coloured pixels as the final layer of each work. The designs reference tapa, a barkcloth created throughout the Pacific. While Samuel’s patterns are drawn from Tongan tapa motifs, they are his own designs and relate to his personal story, including his family’s history of movement throughout the Pacific (his father leaving Tonga, his parents then moving from Dunedin in Aotearoa New Zealand to the Northern Territory when he was small, and again relocating to Meanjin/Brisbane on Yuggera and Turrbal land where he continues to live and work). Acknowledging multiple generations of his family—his grandparents, parents, siblings, himself, his partner and children—these works are an expression of Samuel’s own ongoing interpretation of and connection to culture in relation to place and time.

The lone sculptural piece in the exhibition completes this story of cultural connection. Live Forever (Time Machine) (2019 – 2021) takes the form of a reskinned arcade game cabinet. Screen-printed with patterns that again reference Polynesian design, the machine’s face reads MO’UI ‘O TA’E NGATA, a Tongan phrase that roughly translates as “live forever”. Playful in its reference to 1980s gaming arcades and disco (the screen flashes different colours, lighting up the words “Staying Alive”), this work celebrates the continuation of culture through successive time periods.

As we look at the tapa-inspired designs on Live Forever (Time Machine), Samuel tells me how viewers from many cultures, from across the Pacific and beyond, see similarities between the patterns in his work and in their own cultures. This speaks, of course, to deep connections between cultures. But I think it also speaks to that drive inside us to interpret, to code and decode, and to read things in-line with our own experiences. The works in Low Resolution Dreamz occupy a space between photographs and imagination, replicating the way memories are distorted over time to become closer to dreams than reality.

The exhibition is the latest in a notable move by Samuel away from pop culture imagery and towards more intimate family reference images, which, combined with the overlay of Samuel’s tapa designs, render these works highly personal. Yet the abstraction allows space for viewers to interpret the images in their own way. And because our brains love to build stories, fill gaps, and try to relate, these works also become deeply universal. Standing in the gallery, I am conscious of Samuel’s generosity in sharing these moments from his life, for allowing me to spend time understanding them but also allowing them to become a little bit my own.

Rich with layered meaning and technical construction, these are nonetheless works that anyone can understand and find something within. They are respectful works—of the past, of Samuel’s loved ones and his identity—and they are a joyous reminder of the power of images to connect across time and place.

Samuel Tupou Low Resolution Dreamz is showing 29 April – 4 June 2022 at Onespace Gallery 4/349 Montague Road, West End Meanjin/Brisbane, Australia

About the author

Miranda Hine is a curator, writer and artist from Meanjin/Brisbane. She is a settler Australian woman of European ancestry living and working on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. Her research revolves around the role of museums in constructing and perpetuating particular narratives, and how we can disrupt them. As an extension of her curating, writing and research practices, her art practice investigates our instinct to create stories and connections when objects, text and images are placed next to each other. Miranda has exhibited in multiple group exhibitions, curated exhibitions in museums, galleries and ARIs, and written for artists and publications around Australia.

Miranda Hine is a curator, writer and artist from Meanjin/Brisbane. She is a settler Australian woman of European ancestry living and working on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. Her research revolves around the role of museums in constructing and perpetuating particular narratives, and how we can disrupt them. As an extension of her curating, writing and research practices, her art practice investigates our instinct to create stories and connections when objects, text and images are placed next to each other. Miranda has exhibited in multiple group exhibitions, curated exhibitions in museums, galleries and ARIs, and written for artists and publications around Australia.