Kevin Brophy describes how Omar Musa blends words and the wood carving of Borneo to explore beauty, rage and history

(A message to the reader.)

Omar Musa has, it seems, put aside the voice of protest, anger and challenge so present in his powerful 2017 poetry collection, Millefiori, in favour of a journey to his roots in the culture and history of Borneo.

An island that carries three national flags, its lands have been exchanged many times by colonial powers as wars swept through this part of the globe, obscuring the 50,000 year heritage of its indigenous islanders – tribal groups that include the Suluk, the Dayak, the Perahu and Kedayan peoples.

This book arises from Musa’s desire to “chase that connection” via poetry and the craft of wood carving. He has adopted and adapted images and myths from Borneo’s islands, its creatures, its people and its sea.

This sea surrounding it is the sea-road taken by his ancestors, the Perahu people, to Arnhem Land in the 1700s in search of the sea cucumber, a trade that linked Aboriginal Yolngu Country to Asia. With uncanny timing Omar Musa brings his Australian identity back to Borneo, re-inventing, reversing and re-creating old connections.

“I carve my stories in wood. My ancestors sailed in wood. They will carry me out in wood,” Musa writes.

His dive into wood carving with the woodcut collective, Pangrok Sulap, at the Tamparuli Living Arts Centre in Malaysian Borneo, turns out to be both a return to his ethnic history and a return to the playfulness of his childhood. The resultant book is a graphic marvel.

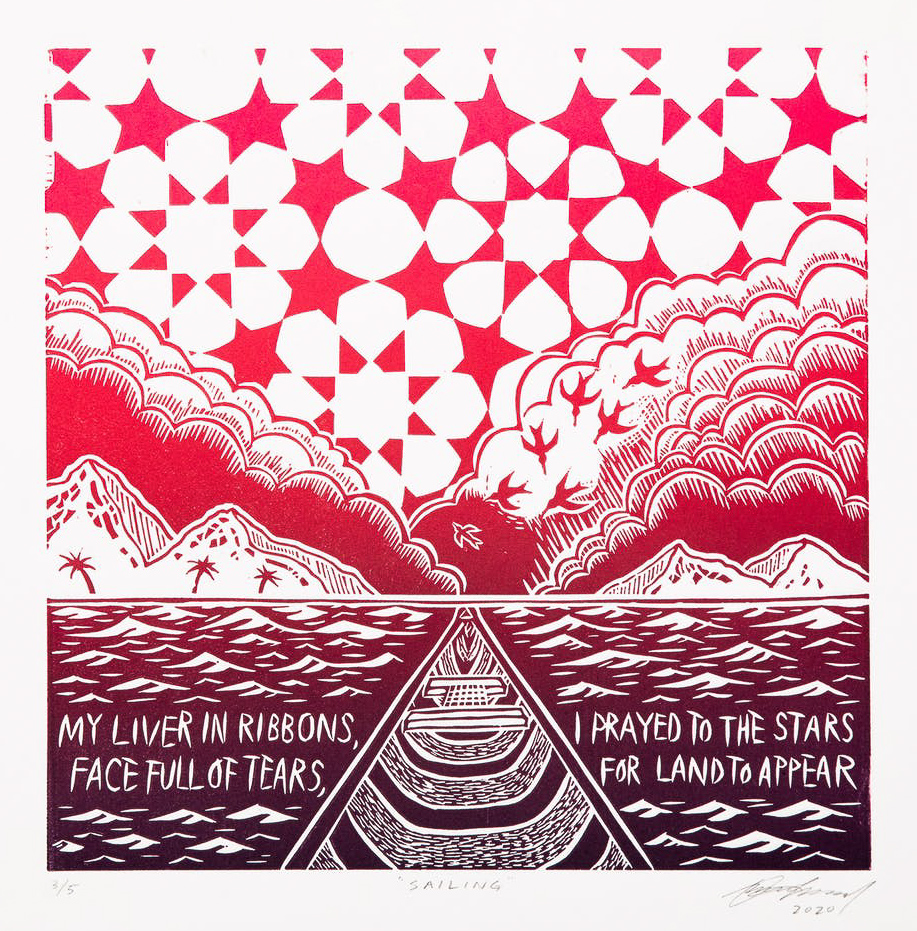

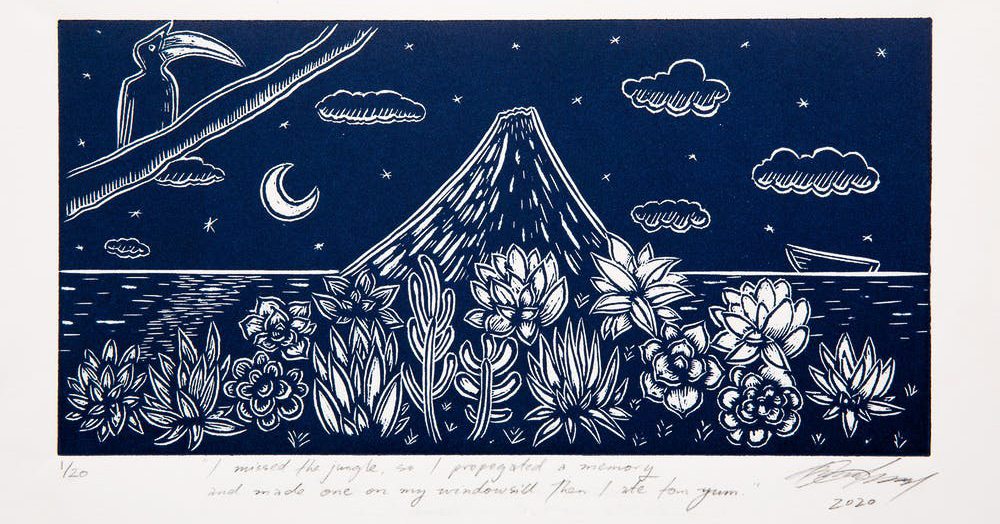

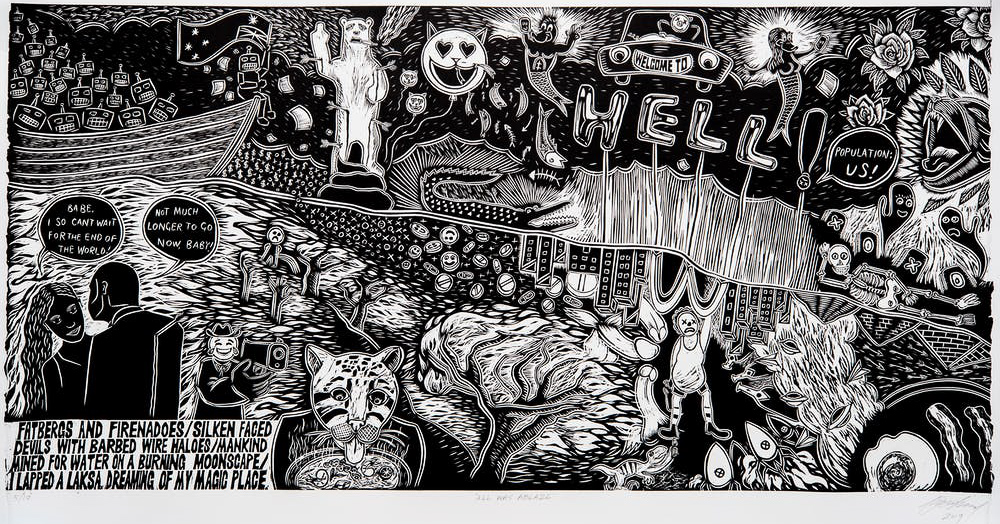

Each page carries images of strong directness, expressive line, joy, sometimes death, and always with a feel for visual balance. You want to tear out each page and paste them to your wall or fridge so that you can stand in front of them and gaze into the images with the attention they demand.

Images of the Clouded Leopard, a vulnerable species in Borneo’s shrinking forests, recur through the book, as does the iconic Mount Kinabulu – and of course the sea in its many manifestations. With a poet so sensitive to ironies, so attuned to the margin, his celebrations of history, nature and heritage here are tinged with despair at contemporary degradations upon nature bringing catastrophic loss upon loss.

This state of affairs is, as the ghost in Hamlet says, and Dylan sings, murder most foul. In this time of shrinking wilderness, encroachment upon wild places, and destruction of deep history, the poet can choose to stand outside the crime and call out the guilty, or bring wider and larger perspectives that declare we, as a species, as a global phenomenon, must share in the guilt as we participate in a violent planetary upheaval.

That Musa has taken this latter path enables his clouded leopard to comment, “I fell asleep dying of thirst but when I woke up I swear I heard a waterfall.” Such poetry is leavened not with hope but with soul.

Sparkles

The poems, some of them inscribed into the mostly black and white wood-carved imagery, are interspersed with mini-essays (one remarkable essay sets the changing national flags that have dominated the island against the recently arrived stateless and displaced people), flash fiction, reveries and prose poems.

Caught in his people’s history, newly aware of the mythic sea, it can seem that matters of immediate politics and protest are no more than the sparkles on the watery surface of a sun-drenched ever-changing planet:

Why? Is a weight that drops into fathomless dark and all that remains is a shudder on the surface of the deep. The border disperses before the hand that signed it into law can finish writing the first letter of its name. The border will be scooped up, laved, shat into, drunk, spat out in Peru, used to distil whiskey in Ireland, and may, one day, come back into my hands in Makassar, where I pour it over my face. When that day comes, and border returns to the latitude where someone tried to name it, its name is now changed, dancing on a braid of kelp, spoken in sand.

(From Makassar)

This writing, like jazz, brings us to the brink of conclusion, only to roll on and up and out into itself and over us gorgeously, but worryingly too, for there are fake islands in the South China Sea:

…. the crescent of sand > so alluring for beach-seeking bottle— > is never what it seems. > words can be fake islands too. > I should have been a dancer

(from Fake Islands)

The imagery in the poems is often exact and masterful, but it’s not lyrical, not bitter, not troubled by having to be an example.

It’s there, it seems to me, because it touched the poet’s hold on his human heart, making the invisible visible so briefly you are not quite sure what has been spoken: the orangutan that watches a man read the Quran each morning–its forest taken from it; getting off shabu (a local term for methamphetamines), the teenager who found kickboxing and God; fever bringing dreams of a snowman to a girl who has never seen snow; a Jeneponto tamarind tree full of fireflies at night becoming a guide to fishermen on their way home from the sea. The soul of this poetry is tender in the sense of being rawly alive to the world.

There is much to linger over and marvel at in these images, and much thanks go to the poet for pausing over them long enough in each poem for us to encounter them.

And this rawness implies an ethics too, and a politics. We are touched by what matters, surely. In this book there are some resurgences of protest as clever and barbed as those in his previous book.

Take the poem that begins, “Lemme tell you what’s unAustralian, mate. Australia” – and ends with

If you’re Black/brown/Muslim/woman/queer/smart/loud

and you dare question a cross-eyed sacred cow,

they’ll twine newspaper headlines

to a noose & lynch you

from a Daily Telegraph poll

in UnAustralia.

The tabloid and online persecution of community worker, mechanical engineer and 2015 Young Queenslander of the year, Yassmin Abdel-Mageid, was one recent public incident that followed the pattern of this unacknowledged UnAustralia, a warning to anyone on the margins who speaks loudly enough to be heard.

Though two clouds can be white and heavy “as four hundred drug busts”, and people “take their coffee and walk their retrievers on sacred sites”, the hills, the hills, “the hills are still here” (from Capital). Does such imagery speak excitement or dread? This is the very question he asks of a portrait of a seated couple, which might in fact be a self-portrait.

The poetry of Killernova arises from a community, from friendships, from family. Poems celebrate shared experiences on beaches, in the sea, or on summer rambles. The poetry of big issues is delivered with immediacy and frankness, and with passing life thrown vividly in at every opportunity – drugs, shit, piss, podcasts, rusty showerheads, music, maps, crowns of thorn, and the unchanging circle of death that brings life (that brings death that brings … ), and love that brings distrust …

A cosmic rhythm

Hard to know where to go once all this has been spelled out. (The book is book-ended by quotes from the restless Elizabeth Bishop on the one hand, and the serene Tomas Tranströmer on the other. Do we go to the ironies of “bad poetry”? To choosing between drinking whole lakes or eating tom yum? Once we know that whatever we do or feel or say is part of a cosmic rhythm woven over unimaginable time with a pattern we will never comprehend, our own individual dance of death and love can seem either sublime or inhumanly monstrous.

Towards the conclusion of the book, after poems which seem to be a response to the end of a love affair, nature re-emerges in its tender details: a spider weaving silk, pigeons in flight, the weighty meaning of an orchid, the quiet hymns of turtles.

Along with this comes a concluding note on the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics by filling the cracks with precious metal: Kintsugi. (The title of the book plays on the 2010 astronomical term kilonova, referring to an enormous release of energy and precious metals when two neutron stars collide.)

If the broken elements can be part of the ultimate history of an object or an experience, pointing to its worth and meaning, then I take it that this poetry of flaws, from a flawed poet who “drank so hard that I shat blood and became a me I hated”, is looking beyond our catastrophically inadequate response to climate change, beyond our UnAustralia, beyond the mistrust we bring to love, towards what?

Not healing, not resolution, not revolution, but perhaps towards that long perspective that makes the present moment everything we have.

For as Tomas Tranströmer wrote, “Everything else is now, now, now.” And given this, it is fitting that this book ends with snapshots of friends and fellow artists at work and sharing meals.

Follow @omarbinmusa

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

About Kevin Brophy

Kevin Brophy’s latest book is the poetry collection, In This part of the World (MPU Inc, 2020). His previous collection, Look at the Lake (Puncher & Wattmann) was awarded the Wesley Michel Wright Poetry Prize for 2019. A past winner of the Calibre Prize for an outstanding essay, his essays and poetry have appeared in many Best Australian volumes and major national anthologies over the past two decades. In 2015 he was writer-in-residence at the Australia Council’s B. R. Whiting Rome Studio, and in 2019-20 at the Keesing Studio in Paris. He has been the Patron of the Melbourne Poets Union since 2004, and he is Emeritus Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Melbourne. In 2021 Kevin was awarded an Order of Australia for services to creative writing.

Kevin Brophy’s latest book is the poetry collection, In This part of the World (MPU Inc, 2020). His previous collection, Look at the Lake (Puncher & Wattmann) was awarded the Wesley Michel Wright Poetry Prize for 2019. A past winner of the Calibre Prize for an outstanding essay, his essays and poetry have appeared in many Best Australian volumes and major national anthologies over the past two decades. In 2015 he was writer-in-residence at the Australia Council’s B. R. Whiting Rome Studio, and in 2019-20 at the Keesing Studio in Paris. He has been the Patron of the Melbourne Poets Union since 2004, and he is Emeritus Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Melbourne. In 2021 Kevin was awarded an Order of Australia for services to creative writing.