- A rare Mughal gem-set gold spoon, India, 17th-18th century; photo: Sotheby’s

- Noor Jahan’s plate: The edge of the Plate is decorated with a Lotus design made of gold thread rubies, emeralds and green glass inlays; photo: Sotheby’s

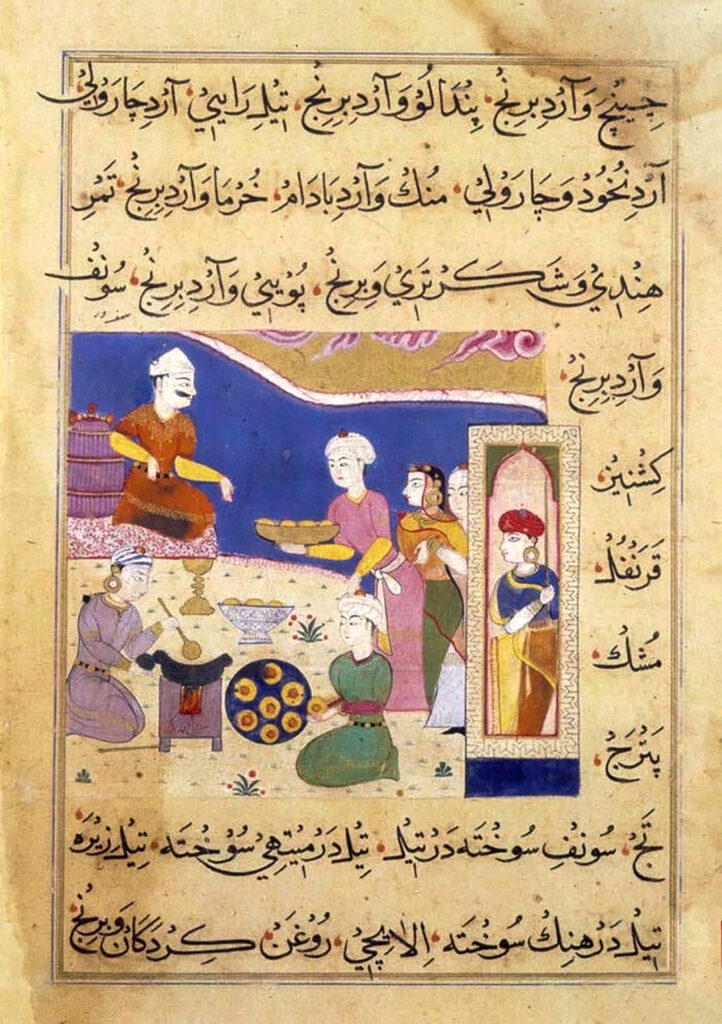

- A banquet including roast goose given to Babur by the Mirzas (1507). Tiriyya; Collection of The British Library

- The Ni’matnama-i Nasir al-Din Shah. A manuscript on Indian cookery and the preparation of sweetmeats, spices etc., 1495-1505. Collection:British Library.

Sahr Bashir evokes the rich culinary history of her Pakistani homeland, kept alive in the silversmithing that adorns it.

South Asian visual, olfactory, tactile, auditory and gustatory flavours can elicit sense memories and possess cultural and economic value for migrant communities to negotiate the binaries of home and belonging. Such sensorial aspects become even more meaningful for those who live far away from home to remember and relive the experiences that may offer comfort in an unfamiliar place. Culturally significant foods and traditional recipes passed down from generations are potent reminders of times spent in the family kitchen preparing and cooking for special events or memorable occasions where sharing food and mealtimes are a way of bringing close friends and often distant or estranged relatives together to reconcile and celebrate the moment.

Seasonal fruits and produce offer an opportunity to create unique flavours, textures and aromas. The languid summer months are especially nostalgic for me with vivid childhood memories of climbing and picking the unripe green mangoes from the leafy trees on a hot afternoon or gazing at the yellow mustard fields on a dusty road trip during the school holidays. The fact that the seasons in Australia are polar opposites to those in Pakistan, my home country, ironically displaces such memories and sends them spinning into a vortex of unanchored thoughts and sensations. While we are shivering through our fiercest of July winters here in the Southern Hemisphere, those green mangoes have already ripened in the hot and humid summer months in Lahore, the luscious fruit plucked off the boughs, the sweet flesh being savoured with every meal and the rest preserved in an assortment of sherbet, chutneys and pickles to enjoy year long. Having moved homes and cities to reside in Australia recently, I can only dream of the tantalising taste of the heavenly fruit from the mango tree growing in my front garden. At moments like these, I feel a twinge of sympathy at recalling the melancholic cooing of the Koel bird, its beak stained from indulging in too many mango treats as legend has it. Except in this case, it is probably less a feeling of empathy and more of self-pity at having missed out on yet another year of savouring a variety of mango delights!

The mango season coincides with the Sawan Bhadhu, the time of year when the tropical monsoon rains arrive in South Asia. Historical archives from the Mughal empire and numerous Persian miniature paintings from the era illustrate a vivid picture of the sensorially powerful mood of the monsoon rains. Images of royal households gathering in the gardens and on the marbled terraces are depicted relishing the cool weather and celebrating the rains through elaborate feasts, dance and music. The sound of the torrential rains falling on the red terracotta-lined pathways, the cool breeze wafting through the sheer muslin curtains, the throaty croaking of frogs in the aftermath of the deluge, all paint a landscape that may be unfamiliar to the eyes when living far away from home, but almost chokingly familiar to the heart and mind. The dull ache triggered by such memories cannot be described in words alone.

Beyond the evocative smell of the rain soaking the parched soil, the phenomena of the monsoon rains are an opportunity to discover the rich gastronomic culture of Pakistani cuisine, especially the unique flavours of seasonal summer cuisine. The aroma of crunchy deep-fried potato, onion and chilli fritters wafting from domestic kitchens in the neighbourhood and the sweet syrupy taste of almond sherbet and salty lassi (yoghurt drink) allude to the distinct taste-scapes that accompany the much-awaited rains. As a South Asian migrant, such sensations act as mnemonic devices to trigger a host of powerful associations around attachment and belonging and are potent reminders of being far away from home. Moreover, these sensory registers resonate with and are representative of the yearnings, dilemmas and identity conflicts around immigrant embodiment according to Martin Manalansan who elaborates on the various facets of migrant experiences through his research findings in Immigrant Lives and the Politics of Olfaction in the Global City (2006).

Tracing the history of food flavours of Pakistan reveals a cuisine as diverse and colourful as the people and the landscape of the country itself. Though neatly divided into four regions or provinces each with a distinct ethnic food culture, the country’s epicurean lifestyle is heavily influenced by its Mughal rulers who developed elaborate cuisines with complex flavours and unique aromas that fused Indian, Persian, Turkish, Middle Eastern and Central Asian notes. The culture of hosting, sharing and giving of food was regarded as a gesture of friendship and generosity as well as symbolised status and power. The court kitchens of emperors were like a melting pot of culture where rich and decadent foods were created by borrowing flavours and techniques from regions such as Uzbekistan, Persia, and Afghanistan and blending them together with the traditional foods of Punjab, Kashmir and the Deccan regions. Using exotic spices like saffron, cardamom and cinnamon as well as dried fruits and nuts from faraway lands brought in through the Silk route by Greek, Roman and Arab traders, the royal kitchen was a hub of experts who painstakingly spent weeks growing, preparing, grinding, roasting, fermenting and slow cooking a plethora of culinary delights to please the emperor and his royal guests.

Ranging from rich stews, meat curries and whole lamb roasts to pickled and stuffed vegetables and smooth gravies with beans and lentils, long hours were spent experimenting and perfecting each recipe. Main courses were accompanied by spiced rice cooked in earthenware pots and baked flaky flatbreads oozing with butter and ghee. Sweet treats included fruity and exotic sherbets (cordials) and creamy, delicately flavoured, silky desserts flecked with precious silver leaf. Competing with and complementing the other, each dish bore the mark of the reigning rulers’ personal wishes, whims and desires.

Emperor Akbar, who ate vegetarian meals thrice a week, had a personal kitchen garden where vegetables were watered with rosewater to make them more fragrant. Noor Jahan, who was Emperor Jehangir’s wife, was well-known for her candied fruits and yoghurt while Shahjahan’s royal chefs developed the most decadent of recipes to match the pomp and grandeur of the emperor’s court. One of the earliest Mughal recipe collections in the form of a cookbook was the fifteenth-century manuscript Ni’Matnama, translated as the Book of Delights. Others like the Nuskha-e-Shahjahani: Recipes of Shahjahan are a celebration of the colours, fragrances, diverse ingredients and local produce of the region that carries the signature of Mughal gastronomical genius, the art of skilfully balancing both vibrant and complex flavours and textures.

Spurred by the rich cuisine, specialised cooking vessels, utensils and tableware developed to the extent that Mughal artefacts include some of the most precious and flamboyant examples of tableware to be found in the history of the great civilizations. Deghs or huge cauldrons to slow cook food overnight, earthenware tandoor ovens, bejewelled plates and spoons encrusted with precious gems and engraved silver drink glasses speak of the mastery of the craftspeople who created a whole range of vessels, each one exceptional in terms of its function, material and form. From the most basic of forms like the Lota inspired by the shapes found in nature such as the lotus and the gourd to more complex pouring utensils such as the Surahi, the designs were customised and detailed to ensure that each vessel did its job flawlessly. Spouted containers, for example, were adjusted according to the contents with narrower spouts for water and wider for more viscous liquids.

Well before the meticulous presentation of the food itself in highly ornamented and opulent serving dishes, the ceremonial act of preparing the ingredients themselves demanded a whole range of specially crafted forms. Each vessel to date, from the choice of material, size and form, carries with it the legacy of ancient wisdom to carefully balance the heat, acidity and release of flavours to maximise its benefits for the human body during the process of digestion and metabolism. Mortars, pestles and slab stones made of marble, stone or wood form part of the orchestra of traditional kitchens producing the deep bass sounds of pounding and grinding the complex array of spices and chutneys in the introductory song. The hollow notes resonating from the unglazed terracotta clay gharas add to the playful tunes by keeping drinking water cool during the sweltering heat and imparting an earthy taste to foods cooked in a haandi over a log or coal fire.

Copper deghs with hammered textures play the role of the grande double bass as they bubble away, their distinct shape fashioned to distribute heat evenly to slow cook silky stews and fragrant jewelled rice. Copper vessels were also used widely for storing and drinking water due to their antibacterial properties and aiding the body’s natural detoxification and anti-inflammatory response. Similarly, brass cooking vessels release zinc which increases the haemoglobin count in blood, and controls the sourness and acidity of foods during the cooking process. The melody is rounded off with the gentle knocking sounds of the wooden belan or rolling pin to flatten the dough which is tossed onto the hot iron tawas or griddles to toast or into the hot oil of the kadai (wok) to deep fry the accompanying flatbreads: fluffy rotis, buttery parathas and crispy puris.

The cutlery is yet another act to behold. The cheeky chimta or tongs work to artfully flip and remove the flatbreads as they exit the hot tandoor oven while perforated spoons called jhanjhri gently coax and manipulate the fried foods to remove the excess oil. The rhythmic stirring of the rich gravies with brass or wooden ladles and the partaking of delicate mouthfuls of creamy desserts using intricately patterned silver spoons remind the user of the time and care spent on carefully crafting each utensil like a violin’s fiddle to enhance the gastronomic experience. Indeed, artefacts such as the Empress Noor Jahan’s dinner plate encrusted with precious gems is not only an icon of the splendour and luxury of the mighty Mughal empire but an ode to the mastery of the artisans and craftspeople who created these glorious objects.

Crafting your own silverware vessels and utensils is an experience quite like no other. After working on a project designing flatware as a postgraduate student and being fascinated by the process, I came upon a valuable opportunity in collaboration with the Anne Marie-Schimmel-Haus, the German cultural centre in Lahore to host a workshop on the art of crafting silver vessels with master artisans from the Walled city of Lahore. The workshop opened a world of endless possibilities for designing, forming, sinking and beating metal into fluid forms to create bold and delicate profiles in the shape of ladles, serving spoons and tableware in particular. Purposefully titled “More Chamchas”, this skill-building intervention played upon the precarious political situation of the country at the time. Chamcha, which is the Urdu word for spoon and also used as a term for a sycophant or a person who gains favour by pleasing others, especially in the context of political horse-trading, the workshop served as a reminder that art and craft can pack a subtle but hefty punch in its own way to deliver a powerful social message.

- Shaping metal on anvil. More Chamchas workshop; photo: Sahr Bashir

- Copper spoon prototype. More Chamchas workshop; photo: Sahr Bashir

Silversmithing is a highly specialised craft where each tool is customised to make the desired mark, shape or profile for a vessel or utensil. Decorative silverware is still highly valued as an art form that relies on the well-honed skills of the most experienced and gifted of artisans, and much of the knowledge and tools of the trade are carefully guarded by the ustaads or master craftsmen who still continue to work with the traditional techniques of their great Mughal ancestors. From beating, quenching and forming to patterning and polishing their creations, each artefact bears the mark of generations of fine workmanship. For the purpose of the workshop, the participants were asked to broadly research the spoon as not only a significant cultural artifact with a rich historical past, but also as a common item of daily use. From primitive tribal spoons fashioned out of bone and wood, to elegant silver spoons giving way to the disposable plastic cutlery of today, participants were encouraged to work towards looking into a unique concept for a spoon. The techniques learnt included forging, forming, doming and sinking that were prototyped and then fabricated into individual designs with the guidance of their mentors.

There is no doubt that each carefully crafted metal form, be it a simple copper bowl or a grand silver urn, comes to life through the magical touch of its creator. The mind that dreams up an idea to visualise an object, the eyes that mark out the shape and size, the hands that beat and caress the metal to make it flow as it takes on a magnificent form fit for a king or a queen. Be it a cauldron of hot stew to feed an emperor’s army on a cold and frosty night or a sweet treat to savour on a special occasion, that experience of holding, being served with or eating with a beautifully crafted artefact is a moment to cherish and a privilege. One that not only enhances the delicate flavours of a fine meal but makes us feel no less than any royal emperor born with a silver spoon in their mouth.

About Sahr Bashir

Comments

I would have to say precious. Rituals becoming more than just a habit, but a special performance. An embellishment or veneration to the food and the people present.