Silje Figenschou Thoresen follows a tradition of improvisation, starting from a mining rubbish pit and ending in a pristine art gallery.

A few days before leaving for the Luleå Biennale I find myself in Ivalo on the Finnish side of the border1.and this is such a giveaway: if anyone uses this expression, “this or that side of the border”, you are talking to a Sámi. You don’t live in Russia, Finland, Sweden or Norway, you live “on the Finnish side”. It’s really just the same place. A lot of borders have been thrown in at various times in history, though., wondering if there perhaps is a way to get to Luleå (on the Swedish side) without going all the way home to Kirkenes (on the Norwegian side) first. If I get my family to drive me all the way down to Rovaniemi I could catch the train, but to save them the extra eight hours each way we all go back to Kirkenes where I’ll take the plane down south to Oslo, transfer to Stockholm, and then fly back up north to Luleå.

All public transport goes south-north. Getting around up north is more of a personal initiative.

After 12 hours flying south and then east and then back up north, I am reunited with my crates of art that were shipped a few weeks ago. We open them and get all sticks and pieces of wood and clamps and ropes out on the floor, and I pretend to remember what goes where.

- Silje Figenschou Thoresen, structure on pillar_details1, 2022, collected materials; artist own photo

- Silje Figenschou Thoresen, structure on pillar, 2022, collected materials; artist own photo

- Silje Figenschou Thoresen. three standing structures, 2021, collected materials; artist own photo

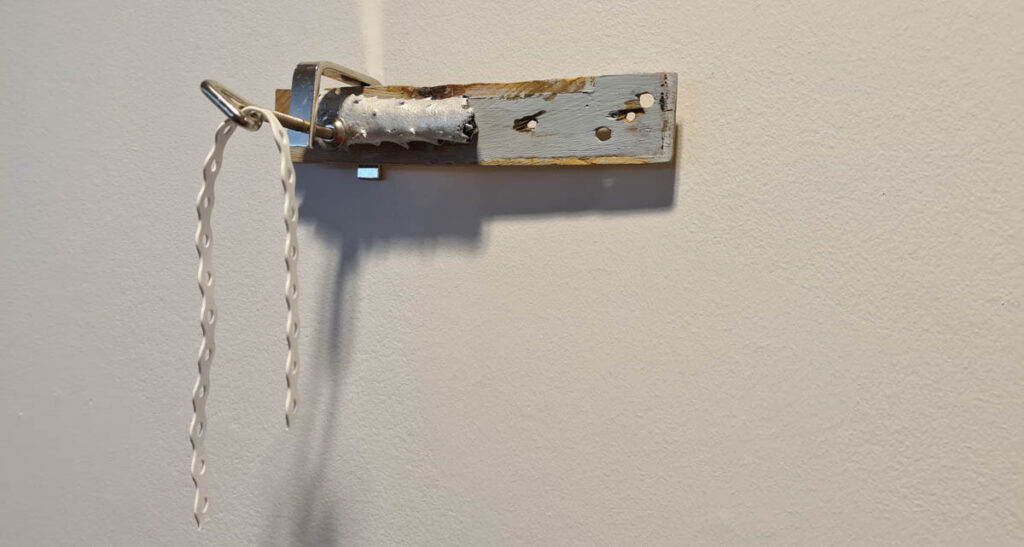

- Silje Figenschou Thoresen, small wall mounted piece, 2020, clamp aluminum cast oak birch bulders band, 20cmx20cmx10cm; artist own photo.jpg

I grew up in a design tradition based on improvisation. This is a tradition where you yourself fix the problems you come across. It can be a repair of a fence, the construction of a container where you can dry reindeer hearts, a smaller object that keeps the hose from the washing machine in place, or a storage building wisely placed in the terrain to keep animals out (high up) or the cold in (placed the last place the snow melts in the spring.). The aesthetic outcome is based on the materials you have at hand, the skills you have or lack, but also the skills of the community around you. The climate, the weather and the landscape also contributes.

I talk about this as a Sámi design tradition, but it is not uniquely Sámi. Many people, especially in rural communities, work like this. However, it is very typical, if not especially unique. We work like this. We save sticks and wood and tarp and wire. Then we make things. Then we don’t need those things anymore, and we take them apart. Sometimes sticks and wire go directly into new constructions, sometimes they are stored for later use. Sometimes they are left to rot. And if you don’t absolutely have to, you don’t change. If a stick is too long for this construction, perhaps a shorter stick can be found. You never know when you need that long stick. All your constructions are stored for later constructions.

I grew up in this tradition, and it is very much a part of me and my everyday life. Also as an artist. This is how I work. Not that I go and invent little problems to solve in my studio, but I try to tap into this kind of material thinking, where the materials lead the way, and a stick never is too long. The materials I have at hand decide the end result. I never saw, screw, glue or change anything. I‘m trying to find a way to work together with the materials I have gathered and then I see what we end up with.

This means that I always have to meet up with the crates of sticks and ropes and metal, and put it back together in the right way, kept up by tension and gravity alone, at the venue. It is always a puzzle and in Luleå, I can’t really remember, so I have to look it up on my own web page. I hide in a corner in the busy crowd preparing the various parts of the biennale and hope no one sees me googling myself.

Turns out that one of the larger branches has gone and dried out quite a bit, which of course makes it much lighter. And off balance. The artwork refuses to stand, it keeps falling over now that the individual pieces do not counter-balance each other anymore. I end up taking a piece of wood from one of the other of my works and then clamp everything together with a metal clamp I hastily borrow from the biennale’s workshop, more or less giving it another leg to lean on.

And then I glue it to the floor. I never glue, saw, or screw. But it does no good to be a fanatic either.

At the next venue, Havremagsinet, in Boden, a short bus trip away from Luleå, I end up completely redoing another of my works. There is such a forest of pillars in the exhibition space, it makes no sense for me to add another, so I end up tying the previously free-standing work firmly to one of the pillars, rearranging everything. I can’t really come in and force down a piece of work without no attention to the room. Everything has to work together as it will be part of the same thing once it is installed. The room is more or less the landscape, as I see it.

Then there is a grand opening. Then I go back down to Stockholm. Then I go to Oslo. Then I fly up north to Kirkenes again, where a thin layer of snow is contemplating on staying for the season, but not just yet, which is fine, because I found some interesting pieces up on the mountains in the spring, but couldn’t get them down just then, and I arrived just in time to get them down and into my studio before the snow hides it all.

About Silje Figenschou Thoresen

I live in Kirkenes, far up in the north of Norway, on a small piece of land wedged in between Russia and Finland. I am north Sámi, and Kven, and also very much a northerner. I work as an artist, based on the design tradition of improvisation that I grew up in, but I also do duodji, the traditional Sámi handicraft. I weave and sew. I have a web page where I’m an artist and an Instagram account where I’m a person. Visit www.siljefig.com and follow @protektoratet.

I live in Kirkenes, far up in the north of Norway, on a small piece of land wedged in between Russia and Finland. I am north Sámi, and Kven, and also very much a northerner. I work as an artist, based on the design tradition of improvisation that I grew up in, but I also do duodji, the traditional Sámi handicraft. I weave and sew. I have a web page where I’m an artist and an Instagram account where I’m a person. Visit www.siljefig.com and follow @protektoratet.

References

| ↑1 | and this is such a giveaway: if anyone uses this expression, “this or that side of the border”, you are talking to a Sámi. You don’t live in Russia, Finland, Sweden or Norway, you live “on the Finnish side”. It’s really just the same place. A lot of borders have been thrown in at various times in history, though. |

|---|