As a Burramattagal woman, Jules Christian finds an inspiring resilience in her totem, the eel.

EELS – who are they? Are they footballers, or are they the ancestors of my people? The eel can move on land and through both fresh-water and salt-water. This is their story and why they are important in my life’s journey.

We conjure up the resilience of the Parramatta Football team in their name, “Parramatta Eels.” We all know that the football team unites in their fight to win the competition. Their wins and losses are vital to the story about why they call themselves the Parramatta Eels and why they wear an iconic symbol of the Eel on their jersey as a shield of pride. Every year the players return, unite and play out their plan of attack. The resilience of the Parramatta Eels is, in itself, worthy of the story below, as is the continuation of the eel itself through its struggles to arrive at its own end-life goal. It is great to win, but the best part of the story is always the incredible journey.

Burramatta

I am a Burramattagal woman from the Darug Nation. We, as Burramattagal people, have a Totem, and we honour our Totem, the Eel. In Dharug language, our name Burramattagal is broken down to mean, Burra = eel, matta = place, gal = the people of.

Therefore, “the place where the eel sets down” is the true meaning of the word Burramatta. Some would say, clear as mud! In fact, by nature the eel is not seen as a show-off, rather it is known for hiding in dark waters, making it hard to spot. Some fish like to stay close to the water surface, but the mysterious eel prefers darker, murkier places. The eel is also known for its strange, but intelligent and versatile survival instinct: its genetic memory gives it the ability to swim in freshwater then transition with ease into the saltwater of the ocean. The eel’s ability to work its way out of the water onto grassy land areas, climb over and go under concrete barriers, stands in contrast to fish that are either just fresh-water, or salt-water variety, and definitely cannot live without water.

Many Burramattagal people became disconnected from Country because of colonisation. As adults, we yearn to return and experience our Country again. This strong connection in us to go home, like the eel, pulls us to find our way.

Where is home? Many Burramattagal people became disconnected from Country because of colonisation. As adults, we yearn to return and experience our Country again. This strong connection in us to go home, like the eel, pulls us to find our way. However, like the eels on their journey to Burramatta, some of us make it, while many through disconnection and trauma do not. This is the strong connection that modern-day Burramattagal people have with our Totem, the Eel, and Country.

What I find amazing is the eel’s ability to survive the long treacherous journey from the Coral Sea when so young, only to complete their end-life cycle and return as an adult to where they first set off. Once they reach their destination on Australia’s east coast, they find their way to “set down”. Hidden in the fresh waters of Sydney, the female eel decides, when the time is right, for her to begin her journey through to the Coral Sea, back to where she was born, so that she can spawn, and die. One mysterious feature of eels is their endurance to overcome many barriers. They survive swimming from one environmental condition into another, facing varied changes in water currents and temperatures, entering ocean pathways, they travel through their life cycle to return to the Coral Sea.

The eel’s journey

These uncanny and strong little “beings” mature into adults in fresh water in readiness for their travel via ocean pathways back to the Coral Sea. Thousands of miles from Australia’s east coast, they make the long journey home when the season is determined to be right and only by them. This process reminds me of the stages of initiation for Burramattagal people in not too distant past times, practised from childhood through to wise men and women in adulthood: the wisdom of endurance only gained through experiences from their individual journey.

For me, I see honour in acknowledging our totem. It is a privilege to understand that the eel has such an interesting life cycle which it determines for and by itself. Throughout the journey, it does not have a marked travel destination mapped out. Nor does it have a map or GPS as we, modern humans need to travel the ocean pathways. It has a deep memory that it recalls. The eel prepares itself with an instinct to survive its life-long journey to where its life began. Once home, the female spawns, only once in her lifetime, then dies, her end-life goal being reached.

The eel in Aboriginal cultures

Before the colonisation process took hold of the continent now known as Australia, traditional methods were used to capture the eel. The stories are etched deeply into rock sites, (as evidence see CSIRO’s Australia Telescope National Facility, 2018). The eel is considered in many countries around the world as mysterious, and by some as ugly, but always as a meal, a prized delicacy to be enjoyed.

The European experience of living on this continent was one of survival in harsh conditions, especially in times of drought. They were challenged to find implements and methods to capture food. Many of the Europeans “tried and tested” tools, implements and methods were taken from Aboriginal peoples. New material mimicked the design of the original tools simply because those original methods worked. Designed thousands of years prior to colonisation, they worked then as they continue to work today.

The eel is smart, preferring murkier waters deeper down, escaping fishnets. The traditional method of catching the eel, by Aboriginal men and women, was to create an “eel trap.” The trap would be lowered into the darker, muddy water. The detail of an eel trap should be respected for the actual time, effort and work involved in creating just one trap. The eel trap entrance is wide to allow eels to enter. Once in, the eels lack the ability to manoeuvre their bodies out from the narrow end of the eel trap, therefore the eel once caught in the trap has no escape.

The traditional way of catching eels was created by Aboriginal peoples although no large amount of credit seems to be given to the thought processes of a group of people who, without technology and academic knowledge like we have today, designed and made the perfect trap. The designs have been copied by others, without the true value of the creation credited back to the rightful creators.

Challenged by modernity

Along with modernisation, colonisation brought more refined, fancier ways of cooking eels. The delicacy of the eel when prepared for cooking was very different from the way Aboriginal peoples prepared the eel to be cooked and served. At the annual Corroborees, the mood was one of unity. There was much feasting and uniting of peoples from different nations, who came to converse, trade and gift their valuables and exchange skills and knowledge. Old scars were mended, and marriage and politics were discussed on Burramattagal land. The eel was respectfully prepared, rolled in bark, then smoked. The bark protected the eel from burning while the flesh was cooked in the smouldering ash and coals.

The eel remains a sought-after delicacy today. However, its declining population has seen scientists and researchers around the world plead for more protective measures by governments to ban exporting the eel so that numbers again increase (Svensson, 2020). Svensson’s book, The Gospel of the Eels reveals the catastrophic future that awaits us, as humans, where the eel and other species are fast becoming critically endangered and require urgent protective action. The eel has survived for thousands of years through the impacts of many changing environmental conditions and has been able to adapt. But sadly eels are now on the decline at an increasingly fast speed and may face extinction.

This decline results from globalisation. Modern living destroys the pristine ocean pathways trusted until now, and creatures of the sea are declining in numbers due to human-made toxic waste which kills indiscriminately. Marine life washes-up along ocean shores, trapped and suffocated in plastic. We people have a responsibility to guard the safety of creatures and ecosystems of our riverways and oceans but have failed miserably at that task. As humans, we rely on and embrace modernisation, but we fail to find ways to protect the living creatures that co-exist with us. Recent years have seen the near-death of the great Darling River where thousands of fish lay bare after suffocation from the toxins poured into the river by human inventions or interference. Rivers affected in Australia are growing in number and humans need to work harder at getting those in power to stop, and rethink the unkind strategies in place, so we can co-exist.

Therefore, it is not only my Totem Eel that has its existence threatened, as mankind continues to threaten into extinction many species. Changes must occur and urgently to protect our animals and birdlife, who are also struggling to survive. If anything can be seen as a positive from COVID-19, it would have to be the cleaner air that returned after the decline in air and sea travel, where humans stayed at home and pollution rates declined. Consumer needs are still being met through the shipment of cargo from one country to another, but a decrease in speed achieved a small window of opportunity to study the environmental factors that have harmed so many species.

Burramattagal Eel Festival

In around March each year, the Burramattagal people continue to celebrate our eel totem and share in this celebration with the broader community at the Burramattagal Eel Festival. In 2016, a brave attempt at reinvigorating interest in a traditional Eel celebration was successfully achieved and now every year people gather around the homestead of John MacArthur at Parramatta.

The festival was the initiative of Mr Clive Freeman, who was at that time the Aboriginal education and interpretation programs co-ordinator for Sydney Living Museums. Now, five years on, the Eel Festival provides an opportunity for people to learn the traditional ways of the old people when coming together in unity. The eel is traditionally prepared and offered to the visitors. Mr Freeman was the architect of showcasing throughout the garden different storytellers, food stalls, a language centre, toolmaking displays, weaving and Aboriginal artists’ products, coupled with guided tours on a path of learning traditional festivities. Burramattagal woman, Ms Jayne Christian attended the Inaugural Eel Festival in 2016 and stated, “It’s taken a long time for this custom to rekindle. This is the beginning of where Australia has to go on much deeper levels, but it’s happening, and that’s a great thing.” she told Rachel Hocking on “The Point”, SBS.

Jayne had attended the sorry business of a prominent Darug community leader, one who always gave her time to Jayne and shared passions with Jayne such as keeping children safe and resolving community trauma.

Upon arriving home, Jayne decided to take a walk by the river to physically and mentally process the sorry business that she’d been part of that day.

While walking along, Jayne noticed that she was not alone and immediately noticed her Totem Eel was following her along and making itself known, by coming to the edge of the water. Jayne acknowledged the eel and the eel continued to keep time with Jayne as she walked along the river.

This was a special moment, Jayne said that she had felt a lot of emotion contemplating the impermanence of life and it felt to her like even amongst the uncertainty of life, the old ones were a constant presence who knew where she was and assured her that their presence was one of the few constants she could rely on.

Naturally, Burramattagal people do not eat their totem but the preparation and gifting are managed under traditional offerings respectfully performed by Aboriginal peoples with ties to the Darug community. The annual celebration aims to gather as live theatre, to engage modern society to appreciate that Darug community, including the Burramattagal people who still exist today. The Burramattagal people who attend are a testament that, no, the coloniser did not destroy Burramattagal people into extinction, nor have they extinguished our Totem Eel.

In todays’ times of “takeover enterprises” by “others” such as non-Darug organisations, councils and white societal rulers, the realisation of the truth, Always was, Always will be Burramattagal land remains as true as its descendants of who survive today. (Evidence of No. 34 of the 1820 Register for Aboriginal students at the Parramatta Native Institute – Brook and Kohen 1991: Han 2015).

We, like our Totem Eel, have journeyed away, continued to learn our lessons, and with that yearning, return to our homeland to show the resilience of Country (Ngurra), Kin (Burramattagal) and Totem (Burra). We have travelled and faced many barriers to coming back home.

As a people who have felt the full impacts of disenfranchisement and trauma, we have learned to take our place in modern society and through resilience, we have gathered knowledge and return to the homeland of Burramattagal people.

Through resilience, the eel faces challenges and barriers as in vast concrete jungles when journeying the Burramattagal waterways. The eel must manoeuvre through concrete channels and climb over walls to make its way to the ocean. We, as disconnected mob face similar challenges, though not through the ever-increasing concrete jungles, but from those who tweak this recent history to deny our existence in today’s world.

I would like to thank Mr Clive Freeman for the knowledge and stories he has shared with me. Mr Freeman, a proud Dharug-Yuin-Wiradjuri man has remained a passionate follower of the Eel and its mysterious journey to the Coral Sea. Mr Freeman and his mum, Aunty Julie Freeman are Darug knowledge holders of the Eel Dreaming stories and Songlines. Further information regarding the Eel stories and Songlines can be made by contacting Mr Freeman at clive.freeman@y7mail.com.

Further reading

Aston, H, 2011, A very fast drain to the South Pacific

Australian Geographic, 2019, The remarkable eels of Sydney’s Centennial Park

Brook, J, and Kohen, JL, 1991, The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town, a history, Table 4.1, Parramatta Native Institution Admission List, 10 January 1814 to 28 December 1820, p.89, pub: New South Wales University Press, Kensington, NSW, Australia.

CSIRO, Australia Telescope National Facility, 2018, Resolute Engraving Site. Compiled images by Stanbury & Clegg 1990

Han, E, 2015, [Reporter], Parramatta Native Institution: Aboriginal children remembered 200 years later, Pub: the Sydney Morning Herald, 20 January 2015.

Jozling, A, Centennial Parklands, 2019, A slippery journey to New Caledonia

Svensson, P, 2020, The Gospel of the Eels, published by Picador, an imprint of Pan Macmillan, The Smithson, 6 Briset Street, London EC1M 5NR.

The CVA Campfire, 2021, Parramatta River Wildlife, Eels

The Point, [Video] The little-known history about Parramatta and eels. 2 May 2016 – 6:14pm, updated 2 May 2016 – 11:01pm.

WaterNSW, (n.d), Amazing eels

✿

About Jules Christian

I am a Burramattagal woman of the Darug Nation, but I have lived most of my life on Wiradjuri Country, at Wagga Wagga, NSW. I have been blessed to have formed strong connections with proud Wiradjuri and Darug peoples, and respectfully acknowledge both. I am currently preparing to undertake further studies of Indigenous Research at Deakin University, with my goal to expand further in Indigenous research through decolonisation which is a central theme to my studies. A cultural practice within my family is to look after the mothers and grandmothers in older age. This practice signifies the importance of sharing cultural practices and knowledge to our young women who become our future strength. I continue this practice.

I am a Burramattagal woman of the Darug Nation, but I have lived most of my life on Wiradjuri Country, at Wagga Wagga, NSW. I have been blessed to have formed strong connections with proud Wiradjuri and Darug peoples, and respectfully acknowledge both. I am currently preparing to undertake further studies of Indigenous Research at Deakin University, with my goal to expand further in Indigenous research through decolonisation which is a central theme to my studies. A cultural practice within my family is to look after the mothers and grandmothers in older age. This practice signifies the importance of sharing cultural practices and knowledge to our young women who become our future strength. I continue this practice.

✿

Maree Clarke: Ancestral memory

An example of how the eel continues to inspire Australian First Nations artists can be found in the exhibition Ancestral Memory.

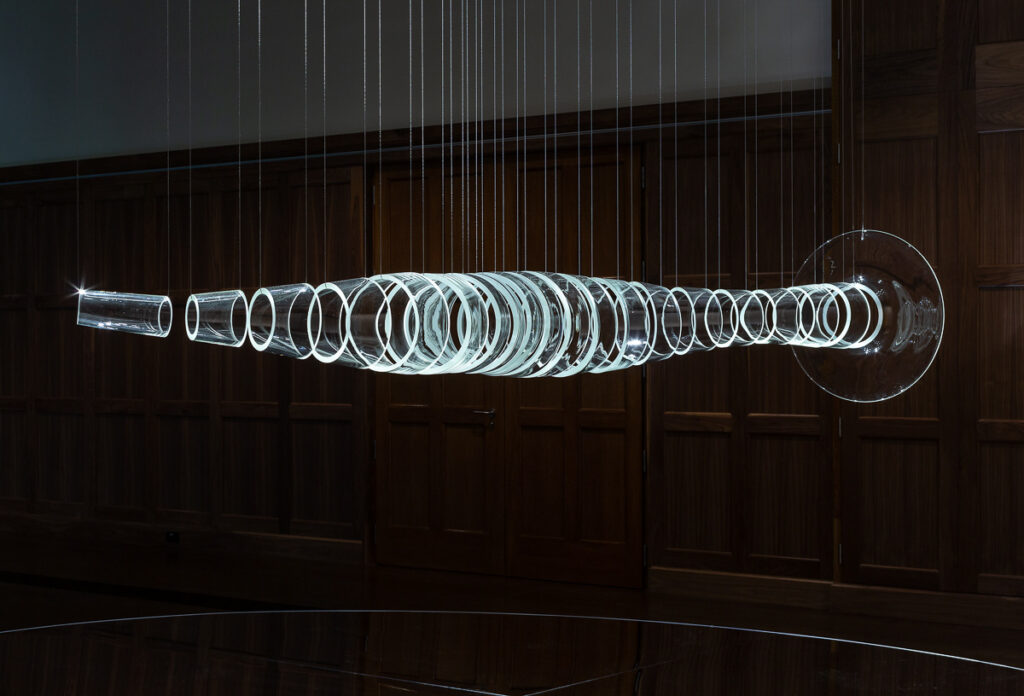

In 2019, Maree Clarke (Mutti Mutti/Wemba Wemba/Yorta Yorta/Boon Wurrung) created a glass eel trap for an exhibition in Melbourne University’s Old Quad Gallery, which were hung alongside traditional fibre traps. The university is currently working with Jeffa Greenaway on a new landscaping for the campus that tells the eel story.

Comments

Brilliant work on culturally articulating the life and purpose of the mysterious eel.

I like the Burramattagal story. It tells us about the significance of learning Oral Traditions that deepen our knowledge about our history as a community/people and strengthen our resolve to survive and continue asserting our identity as well as our habitat-our land, our communities. Before reading Jules Christian’s article, I was ignorant about the travel of the eel from freshwater to salt-waters and back to the freshwaters to spawn and then die. What a remarkable story of life! The eel trap – glass as shown in the photo at the Melbourne show, embodies the swift body movement of the eel. It however does not show the resilience of the eel in its life’s perilous journey.

My name is Gregory Archibald l a descended pallarwa my father told the skill of cooking eel . First catch one , then cook him over hot coals with a hessian over. But if you cannot buy a bag from the white fella steal one. If you cannot find an eel steal one from that English lackey called the governed Something from the botanical gardens .