(A message to the reader.)

Lee Tran Lam finds four remarkable chefs who make their own tableware, uniquely crafted for their specialist dishes.

When chef Ryota Kumasaka took over Sydney’s O’Uchi restaurant in late 2022, he didn’t immediately alter the menu. “But I changed the plates, because I’m a pottery artist,” he says.

His rugged, hand-crafted tableware has long been a fixture at his other Sydney venues (Shinmachi, TenTo), but O’Uchi’s staff needed time to adjust to the change. “They’re very nervous using the hand-made bowls because they’re used to plastic,” he says and laughs. Waiters might have anxiety about dropping these long laboured-over pieces, but there are many great reasons for presenting dishes on unique designs.

“We expect good things when we see food coming out on beautiful plates or there’s special cutlery set at the table,” says Claire Ellis. Like other chefs – such as Pipit’s Ben Devlin and Bar Copains’ Morgan McGlone – she knows that creating pieces by hand can enhance the dining experience in a profound way.

Ben Devlin

Visit Pipit

Diners might see fish bones as a nuisance, but Ben Devlin knows they can become tableware. Tuna spines from his seafood supplier were destined to be thrown out—until he collaborated with Leia Sherblom of Grit Ceramics to upcycle them.

Being creative with skeletal scraps reflects the sustainable approach of his restaurant in Potsville, northern NSW. For Devlin, the idea of turning carcasses into crockery was inspired by ceramicist Gregg Moore, who has transformed leftover beef bones from New York’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns into plates and other pieces for the restaurant.

“To be honest, that was the first time I clocked onto the concept that bone china was literally bones,” Devlin says. “It’s bone china because there’s bones in it.”

Refashioning tuna spines into tableware is an involving process (the bones must be cleaned, boiled, roasted, taken to Sherblom to be kiln-fired, pulverised, sifted and so on) and early experiments weren’t always a hit.

“Unfortunately, because the fish bones have a salt content, the salt would conduct electricity through her electric kiln,” he recalls. “So we sort of damaged her kiln, which was not ideal.”

A broken shopping trolley, loaded with a gas burner and shelving, became their alternative kiln instead.

Pipit’s relationship with Grit Ceramics has produced 1500 unique pieces for the restaurant. One impressive example is the porcelain fish vertebrae model, glazed in fishbone china. “That’s made to be served with the biscuit we make out of fish-bone flour, which we then top with fish-bone caramel.” Custom shells, glossed with oyster shell glaze, are perfect vessels for Pipit’s oyster custard and bunya nut miso dish. Ceramic anchovy ‘tins’ are a playful way to present bonito preserved like the salty fish.

“At the end of the meal, we give people a map, and it highlights where things have come from,” he says. It showcases farmers and distillers Pipit sources from, as well as local makers like Sherblom. Devlin credits partner Yen Trinh for illuminating this aspect of Pipit through her designs. It’s another way they can tell “a story about our area and our business”, he says.

Claire Ellis

Visit www.claireellisceramics.com

Many years before Claire Ellis became a ceramicist, she was a chef at Sydney’s Quay. “It was the first restaurant I worked at that used mainly handmade tableware,” she says. They came in such a dazzling range of shapes, colours and textures. “It was like unlocking another dimension.”

These unique pieces gave her an invaluable arts education as she moved from top restaurant to top restaurant. “I spent almost a decade inadvertently doing visual and tactile research on tableware,” she says.

For health reasons, she retired from restaurant kitchens to run her own studio in April 2021, but her time as a chef has clearly contributed to her artistry. Her honey ant dish was created for Melbourne’s Attica while working there: its earthy pillar shape is inspired by the tunnels produced by the insects in the Kalgoorlie desert. These honey ants are known as Nyamanka by the local Tjupan women who harvest them.

- Claire Ellis, Sand plate, stoneware, photo: Chris Hopkins

- Claire Ellis, Bull Kelp plate; photo: Duncographic

Ellis was given free rein on that commission. Some other restaurant projects are more collaborative.

“Lûmé wanted a few designs for some of their seafood snacks that reflected the Port Philip Bay Area,” she said. “They asked if I could make the plates look like they were found in nature, so I made a bowl inspired [by] abalone shells, a small plate for tartlets that looked like two halves of a scallop shell, a plate resembling dried bull kelp and a plate with a sandy texture and colour.” She added small dunes and holes to this plate, so the restaurant could position ingredients and garnishes in striking ways.

“With my tableware, it’s the best feeling when people tell me my creativity has inspired them,” she says. Diners at Attica wanted to meet her because they were moved by her artistry and she was caught off-guard by how many people responded to her In Any Way Shape or Form exhibition at Brunswick Street Gallery, which showcased 100 plates on form and food waste. “It’s always rewarding seeing people interact with what I’ve made,” Ellis says.

Ryota Kumasaka

- Cup for Tento by Ryota Kumasaka

- Restaurant dish by Ryota Kumasaka

- Cup for Tento by Ryota Kumasaka

Visit Shinmachi, TenTo and O’uchi,

“I was surrounded by a lot of good pottery when I was growing up,” says Ryota Kumasaka, who is originally from Fukushima, Japan. The country has produced earthenware pieces for over 10,000 years and he recalls seeing “millions” of “beautiful plates” with “unbelievable-looking glazes” in Japan.

Plus, the craft runs in his blood. “My mum was a pottery artist,” he says.

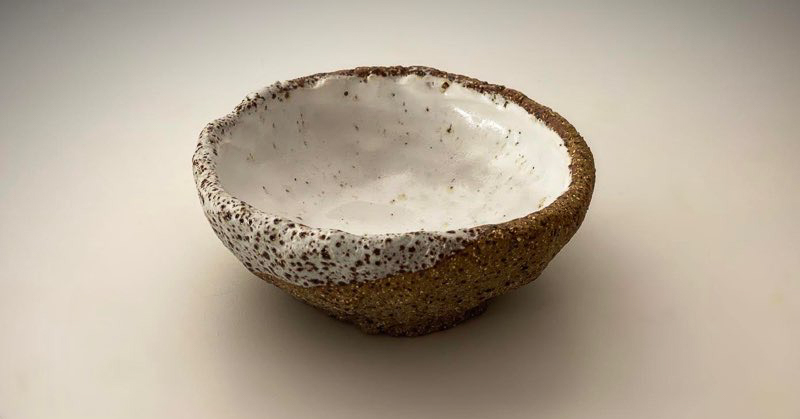

Despite experimenting with pieces for his mum’s cafe early on, Kumasaka only began seriously pursuing pottery around four years ago. He wanted to create “super unique” tableware for his restaurants. Although professional potters might prefer bowls without fingerprints or bumps, he likes these human touches. “When I look at mine, I go ‘there is not enough bumps!’”

He seeks out inspiration in unusual places, too. “Sometimes I go around gardening shops or craft shops or whatever, just to look for shapes and I always think, ‘this is an interesting shape, but can I put ramen in there?’”

The rough-hewn ramen bowls at his Shinmachi, TenTo and O’uchi restaurants are definitely unique – with their raw finishes and imperfect, hand-pressed surfaces. What makes them even more striking is when wooden planks are placed on top, like a bridge holding extra accompaniments.

Kumasaka also creates bowls just for TenTo’s ochazuke. Traditionally, this dish was a way to maximise old rice by infusing grains with hot tea. The cafe’s version is more elaborate than the humble Japanese staple, though. So his bowl is shaped to emphasise the sculptural rice ball, the billowing rice paper basket on top and the shallow broth the rice bathes in. “We call them ochazuke bowls because we just do ochazuke in there.”

He also makes soy sauce dishes that resemble miniature stools and likes to produce ceramic glazes from scratch, too. He compares this to creating your own teriyaki sauce as a chef. “You have more control,” he says. “You can basically literally make any glaze you see in the market. It’s scientifically possible. It’s basically a matter of putting in the effort to get there.”

Morgan McGlone

Visit Sunday and Bar Copains

Creating the plates, bowls and condiment dishes for your wine bar by hand. It sounds romantic in theory, but the reality can be very tiring. “I’ll never do it again,” says Morgan McGlone.

For Bar Copains, which recently opened in Sydney, the chef produced 70 dinner plates, 20 larger share plates, 70 side bowls, 80 ramekins for seasonings and 70 versions in a larger size “with a beautiful brown raku clay”.

The bar is also stocked with 22 water bottles and 20 coffee cups. “We don’t even have coffee,” he says. “So that was a bit of a waste!

Then there are the pasta bowls, which need to be redone. “They didn’t set as I would have liked and sometimes they rock, but they do the job for now.”

There are another 20 salad bowls on the “to do” list. But when you’re juggling another restaurant as well (Sunday in Potts Point), while parenting a three-year-old son, it’s hard to find a spare moment to shape, fire and finish more pieces.

Although his mother is a ceramicist, McGlone only learnt the craft recently in 2019. His pottery was incredibly heavy at the start (“some of them were like dumbbells”) and he used to overdo it with glazes. Now he likes to leave clay exposed.

The chef is inspired by a wide range of vessels—from Japanese kyusu teapots to Korean onggi pots—and sells pieces (sushi platters, bowls) on the DRNKS website. “I’m obviously humbled but really surprised when someone buys a teapot for $120,” he says. While clay is a cheap material, the price tag reflects the immense labour that goes into throwing, trimming, firing, sanding down, glazing and refiring each piece. That doesn’t even include the design or studio-hiring fees. “I don’t think people understand how much work goes into it.”

McGlone’s studio is named Ryo’s Pottery, after his toddler son. Have they collaborated on anything yet? “No, he does play around with clay—but I’m so scared he’ll eat it,” says the chef. Then he changes tone. “It’s not so bad, he’s eaten worse stuff. He’s eaten his dad’s cooking, so that’s okay.”

About Lee Tran Lam

Lee Tran Lam is a freelance journalist based in Sydney/Eora, Australia. She’s the editor of the New Voices On Food books and presenter of several podcasts: The Unbearable Lightness of Being Hungry, the Culinary Archive podcast and Crunch Time.

Lee Tran Lam is a freelance journalist based in Sydney/Eora, Australia. She’s the editor of the New Voices On Food books and presenter of several podcasts: The Unbearable Lightness of Being Hungry, the Culinary Archive podcast and Crunch Time.