- Aboriginal rock engravings, Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, photo Driectin, 1982 creative commons lic, Wikimedia

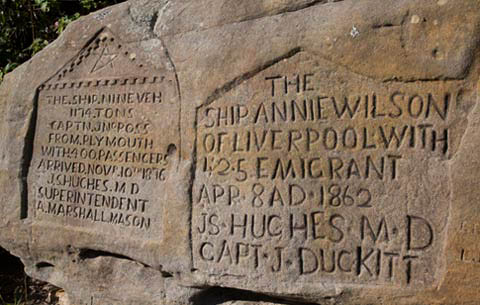

- Sydney Quarantine Station, rock Inscriptions, photo ‘Stories from the sandstone’ sydney.edu.au

- Manly Kangaroo 1856 photo Sardaka Sept 2017, creative commons lic, Wikimedia.com

- Aboriginal keystone, 1866 National Art School, Darlinghurst. photo Peter Emmett

- Lands Department building, Bridge St facade, Sydney, photo Whiteghost.ink, creative commons lic, Wikimedia.com

- Sheila Hicks installation, recycled towels, Crafts Councils Centre Gallery 1982, photo Peter Emmett coll

- Mitsuo Shoji Form in foreground, Origins exhibition Crafts Councils Centre Gallery 1982, photo Peter Emmett.

- Heather Dorrough, Self Portraits series detail, embroidered fabrics, 1983, Crafts Councils Centre Gallery, 1983, photo Peter Emmett

- Peter Tully, Urban Tribalwear outfit, plastics 1982, Elements of Change Exhibition, Crafts Councils Centre Gallery, 1982, photo Peter Emmett.

- Seidler House kitchen after reconstruction 1988, photo Peter Emmett

- Elizabeth Bay House saloon, after paint reconstruction 1988, photo Peter Emmett collection

- Hyde Park Barracks hammocks reconstructed 1991, photo Peter Emmett collection

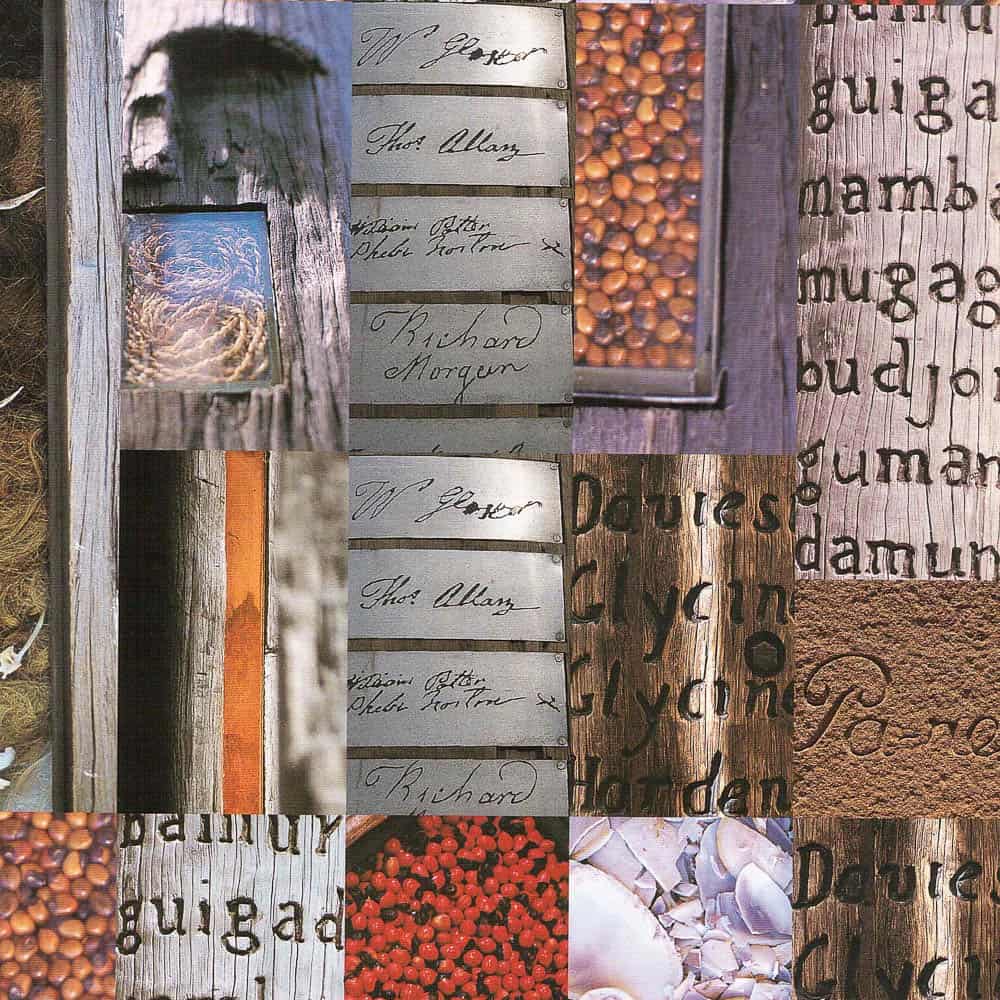

- Edge of the Trees, Janet Laurence and Fiona Foley, 1995, collage of material details MOS design

- Shell fish hooks, Sydney region, Australian Museum collection, photo Australian Museum

- Dixson Collectors Chest c1820. Dixson Galleries, State Library NSW, photo State Library NSW

- Harbourings, Remaking Sydney’s Industrial Landscapes, an exhibition at the Museum of Sydney 1997, photo Peter Emmett

- Under the Walsh Bay fingerwharves 2019 photo Peter Emmett

Sydney is a crafted city, a drowned river valley shaped from stone, wood, water and us. It gives of itself to make itself. We shape it and it shapes us in turn. Tides and winds drift through this harbour city like shifting moods, memory and imagination. And so a life is also crafted here, through transformations of matter and memory. Let me share some reflections on living in this crafted city for over 60 years.

1 Matter and memory

Sydney is sandstone at its core. Many have crossed and grooved its soft porous surface. I have explored their traces on many Sydney rambles since childhood. From Balls Head to Bondi, rock engravings still hold the stories of Sydney’s Indigenous people. At the Manly Quarantine Station other rock engravings reveal messages of dream and dread by migrant strangers. Nearby in Kangaroo Street, a stone kangaroo gazes at the Pacific from a sandstone ridge, a remarkable work of Sydney colonial folk art c1856. Above the 1866 entrance to E Wing of the old Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School, is a superbly carved keystone of an Aboriginal man’s head. Even more outstanding is the possibility that it was made by “Billy of Namoi”, an Aboriginal stonemason in prison at the time. In the CBD the majestic Lands Department building c1892 has a series of life-size heroic statues of colonial explorers standing in alcoves. These stone cold dead white men will soon grace the facade of a Chinese hotel. The story of Sydney crafted in stone.

Some depict 1950s and 60s Sydney as a new age of consumerism, but my memories are of a world of making. My father built shelves into every corner of each new house, twelve in all, while mum sewed every surface. She was a couturier, my aunties were florists, hairdressers and cooks, my uncles were carpenters, stonemasons and shipwrights. They were crafting a post-war Sydney home and life for us.

2 Community

In 1971 I bought a derelict terrace in Glebe for $10K. By day I crafted a home from brick, plaster and wood, gleaning scrap materials and know-how from old hands at timber yards, plaster and plumbing supplies. At night I wrote a PhD on my youthful hero William Morris. His socialism has had a profound and lasting impact on my worldview, based on the necessity of creative work and a utopianism, not as nostalgia but as a disciplined dreaming of future possibilities.

It actually felt like this in 1970s Glebe. New inner-city settlers were crafting a community, a step ahead of dodgy developers. Some potters inhabited an old chrome factory, later forming the Inner City Clayworkers Gallery in the shopfront of my home. Blackfriars Gallery featured craftworks by local legends Derek Smith and Peter Travis. The Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre was breaking new ground in St James Hall. Nearby Demeters bakery crafted biodynamic bread in an old flour mill.

In 1979 I chose hands and heart over the academic head and took on the job as Director of the Crafts Council of NSW. In the late 70s crafts seemed the panacea to all our social ills and alienation. It was a privilege to work with the remarkable Jane Burns, Director of the CCA, an inspiring mentor. I remember other strong women such as Viv Binns, Liz Jeneid and Suzanne Holman, makers as catalysts for community arts and interaction. Joe Eisenberg took crafts to suburbs, factories and unions while Vic Keighery staged spectacles in parks and beaches. Everywhere it seemed people were crafting a community.

3 Gallery

In 1982 I found my calling making exhibitions, crafting the juxtaposition of things into spatial installations. As Director of the new Crafts Councils Centre Gallery, a cavernous space in the old Mariners Church in The Rocks, I became a fellow traveller in a vibrant world of makers. Here too I forged a personal and professional partnership with the phenomenal Anne Flanagan. We lived in a breezy wooden house in Woolwich with renovation as rent. It looked out to Cockatoo Island where hundreds of men still crafted ship parts from lumps of metal. The ferry to the gallery in The Rocks passed through Sydney’s maritime world in metamorphosis.

At the CCC Gallery, with over 30 exhibitions in three years, it felt like we were in the epicentre of a Sydney zeitgeist, transgressive of craft traditions, arts boundaries and social mores. From Parramatta Gaol we collected long cloth roll towels which Sheila Hicks transformed into a giant “waterfall” installation. Peter Travis stitched vibrant fabrics into soaring kites, as colourful as his personality. Heather Dorrough embroidered portraits of her own psyche. Mitsu Shoji’s bold blackened forms sat with Jenny Orchard’s crazy spiked punk funk with African patterns. Radical patterns splashed across fabrics by Jenny Kee, Linda Jackson and Deborah Leser. Michael Keighery made assemblages of clay and concrete, Warren Langley of glass and neon, Robyn Gordon’s wearables of Fimo and found objects, Lyn Tune’s of feathers, flesh and steel and Peter Tully’s urban tribalwear of anything goes. We showed Marc Newson’s Lockheed lounge when he was still at art college, now considered the world’s most expensive contemporary object. And who could forget the joy of showing those exquisite shell works by Mavis Longbottom and Lola Ryan from La Perouse.

Our annual Christmas Shows were something to behold, giant celebratory emporiums of Australian crafts, with hundreds of makers from Sydney and beyond. Equally bold were major exhibitions celebrating works from Aboriginal communities, the Pacific, Indonesian archipelago and India. Sydney celebrated itself through crafts and cultural connections with our neighbours. Whatever happened to these utopian aspirations to craft a creative city in our region? I can’t really imagine such work and exhibition projects happening again, the sheer audacity of scale and risk, such time-consuming passions on a shoestring.

4 Symbol

1988, curating the Bicentennial Travelling Exhibition into Daryl Jackson’s inspired tent city with over 300 commissions by Australian makers, provided some memorable Sydney experiences. A visit to Lloyd Rees’ Lane Cove studio to loan his easel and palette/traymobile caked in paint the colours of his beloved Sydney Harbour. To the Palm Beach studio of Bruce Goold, Sydney’s consummate pattern maker. Peter Callas crafting a digital composition from his Fairlight computer in Balmain. In Botany Andrew Jackson casting an acrylic car body embedded with postcards, and Peter Tully and Ron Smith assembling a mini Mardi Gras parade with cupie dolls in Darlinghurst.

We lived in Lilyfield on the edge of Callan Park, another renovation in a suburb in transition, sharing streets with old craft broom makers and joiners, new craft studios and film prop makers. My introduction into the mad world of film prop makers and scenic artists was the biggest surprise and delight on this Bicentennial Exhibition project. They have remarkable craft skills and improvisation without the fetish for the object or its collection – a sandstone cave, a picture palace, an acrylic car. Marcus Skipper was a magnificent maker. So was the late Brian Hocking, a mastercraftsman who could make anything from anything.

Strangely, when I discovered Brian Hocking’s passion for mid-century modernism I engaged him to almost single-handedly restore and reconstruct Rose Seidler House c1951 – casting light fittings, refurbishing appliances, reproducing asphalt tiles and laminex benchtops. For all the talk of a “machine for living”, Rose Seidler House was very hand-made. Its sandstone foundations and fireplace were carved from the site and its bespoke cabinets, fabrics and fittings were innovative craft design. Another postwar Sydney story of crafting place from space.

5 Heritage

Another decade with the Historic Houses Trust NSW, the 90s, immersed me in another world of Sydney crafts – the building conservation artisans. Master painter Charlie Penlington identified paint colours from the lazy spots of the colonial painter on Elizabeth Bay House cornices. Master joiner Gary Waller shaped Hyde Park Barracks hammock rails. Master sailmaker Harold Browne made a hammock prototype for Balmain sailmakers EH Brett to reproduce multiples, including complex rope splicing. Lindie Ward stitched superb replicas of convict clothes. On the site of first Government House, monumental mason David Ayoub carved names into stone columns of the Edge of the Trees.

What is special about these artisans is not only their own knowledge and skill but the way they sense the past maker in the present material, a wonderful empathy across time. A city is like this too. We sense the presence of those who have been before and the ways they have crafted place from space. I reflected on this daily on my harbour ferry ride from home to work. We now lived in Birchgrove, perhaps the last renovation, between the beautiful stone wall of the old Mort Dock and the timber shipyard of master boat builder Nick Masterman.

Taking on the First Government House project in 1992 flooded me with all these issues about Sydney’s origins. The concept for the Museum of Sydney, as it was later called, evolved as I witnessed how archaeologists and heritage specialists made such a fetish of relics of the lost house while disregarding the ancient cultural landscape it was crafted from. This site was not a birthplace but a meeting place at the edge of the trees. When the 1500 strangers arrived in 1788 and met about the same number of Eora in their harbour home, those 3000 people became entangled in a crucible of colonialism. We are the products of that entanglement and subsequent generations engaged in crafting this city as we know it. The crafting of Sydney was the main message of MOS. You entered the museum through the Edge of Trees, against a giant backdrop of the Sydney environment—stone, wood, water—with assemblages of objects and images used to transform and represent place.

In retrospect, the most satisfying achievement of MOS at its opening in 1995 was the display of hundreds of significant colonial objects—the cream of Sydney folk art. It’s a myth that Sydney had no folk art. Those special Eora bark water carriers and finely-crafted shell fish hooks, those tiny straw models by Sisters of Mercy to shape a new life in Australia, convict love tokens, paintings by travelling folk artists Augustus Earle and Jacob Janssen, and the outstanding collector’s chest known as the Dixson chest. In this endeavour, I pay tribute to Caroline Mackaness, a magnificent curator of historic objects.

6 Haven

Since 2000, while I have had the continued privilege of working on the interpretation of some major Sydney sites in transformation—the Homebush brickpit, Barangaroo headland— strangely most projects have been interstate. But I always return home to my Sydney haven. I have kayaked the intimate edges of this harbour haven for 25 years now and it never ceases to amaze and inspire an uncanny sense of the strangely familiar, of continuity and change, nature culture entangled, people crafting a life and a city across time. A powerful abiding memory is kayaking under Sydney’s finger wharves through a drowned grove of trees—40,000 turpentine piles dotted the harbour bed in its wharfing heyday. The play of light, shadow, pattern, texture, motion, a celebration of the senses, but also of the materiality of crafting and recrafting these timber wharves over time.

Like these wharves, Sydney is an incredibly three dimensional city, as if crafted from raw materials, not laid out like a map or viewed like a postcard but shaped from matter and memory like a crafted object. Curating an exhibition is like this too, juxtaposing things in space to choreograph people through its shifting shapes and moods.

As a curator, I have had the privilege of crafting many exhibitions—about 50—of many things from many collections. I have not only mined the great Sydney collections—Australian Museum, Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Australian National Maritime Museum, Macleay Museum—but also delved into many small museums, government departments, companies, unions, industrial sites, historic places from Opera House to humble homes, and many private collections of curious and knowledgeable collectors. Above all are the studios of Sydney makers and their wonderful material chaos and generosity of spirit. In retrospect, it’s not single objects that feature in my memory museum, but their diversity and abundance. It’s not really objects at all, but the sheer inventiveness, skill and know-how of people who crafted them. All my exhibitions over the decades have been about this. As I learnt from William Morris, it’s the continuing celebration of creative work in crafting our identity and urbanity that endures.

Yes, Sydney is a crafted city, like an exhibition, a home, a life.

Author

Dr Peter Emmett is a Sydney curator, historian, writer and interpreter of the meaning of sites, spaces and collections. After a PhD in History he was a Tutor in History at University of Sydney (1975-78). As Director Crafts Councils Centre Gallery (1982-85) he curated over 30 exhibitions on contemporary crafts and Indigenous cultures from the region. As Senior Curator Australian Bicentennial Exhibition (1985-1988) he masterminded six exhibitions into the travelling tent city. As Senior Curator Historic Houses Trust NSW (1988-2000) he developed a series of new and highly acclaimed museum projects – Rose Seidler House (1989), Justice and Police Museum (1990), Hyde Park Barracks Museum (1991) and Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House (1995). As an independent curator since 2000 his curated projects include Long Gallery, Australian Museum Sydney (2015-2017), Museum of Economic Botany, Adelaide (2005-2010), Separate Prison, Port Arthur Historic Site (2005-2008), and Shark Bay Interpretation Centre (2004-2006).

Dr Peter Emmett is a Sydney curator, historian, writer and interpreter of the meaning of sites, spaces and collections. After a PhD in History he was a Tutor in History at University of Sydney (1975-78). As Director Crafts Councils Centre Gallery (1982-85) he curated over 30 exhibitions on contemporary crafts and Indigenous cultures from the region. As Senior Curator Australian Bicentennial Exhibition (1985-1988) he masterminded six exhibitions into the travelling tent city. As Senior Curator Historic Houses Trust NSW (1988-2000) he developed a series of new and highly acclaimed museum projects – Rose Seidler House (1989), Justice and Police Museum (1990), Hyde Park Barracks Museum (1991) and Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House (1995). As an independent curator since 2000 his curated projects include Long Gallery, Australian Museum Sydney (2015-2017), Museum of Economic Botany, Adelaide (2005-2010), Separate Prison, Port Arthur Historic Site (2005-2008), and Shark Bay Interpretation Centre (2004-2006).

Comments

Great read! And really nice to be reminded of recent histories. We forget all too easily!

Hi Peter,

Your article was passed on to me by one of my students. We would love to learn more about the keystone with a carved Aboriginal head here at the National Art School. Could you let me know your source for the “Billy of Namoi” reference?

Cheers,

Molly