Samorn Sanixay reflects on the uses of decomposition in textile dyeing and how it resonates with Buddhism and the refugee experience.

Autumn

Each year, as the end of autumn nears, there is a change in mood and a smell in the air. As the days shorten, the trees and vegetation around us also prepare for the winter. Unlike humans, where we add layers, trees and plants shed theirs.

Most green leaves and vegetation in this world exist to provide us with food.

When the leaves have had their day, they take their last breath and drop to the ground.

The knowledge obtained from biology combined with Buddhism is how I approach my creative process.

All the handwoven textiles produced in Laos are near perfect with mostly geometric, symmetric patterns and motifs. In my personal works, I want to disrupt this process because I want to be the opposite of perfect.

Decomposition can be described as the end of life but it is also the start of life. In biology class back in high school, I learnt that the most important thing in the entire rotting process is carbon, the physical basis of all life on this earth.

The carbon cycle begins with plants, combined with carbon dioxide, sunlight and water.

Buried silk

Many years ago on a very hot summer’s day, I decided to experiment with burying one of my handwoven Lao silks into the dirt of a vegetable patch. As rice paddy mud in Laos is used to produce shades of charcoal and blacks, what would the soil in Bondi do?

I loved the idea of the finest handwoven silk being buried in the earth. Because despite its reputation for being delicate, silk absorbs colour better than all other fibres and it is the toughest.

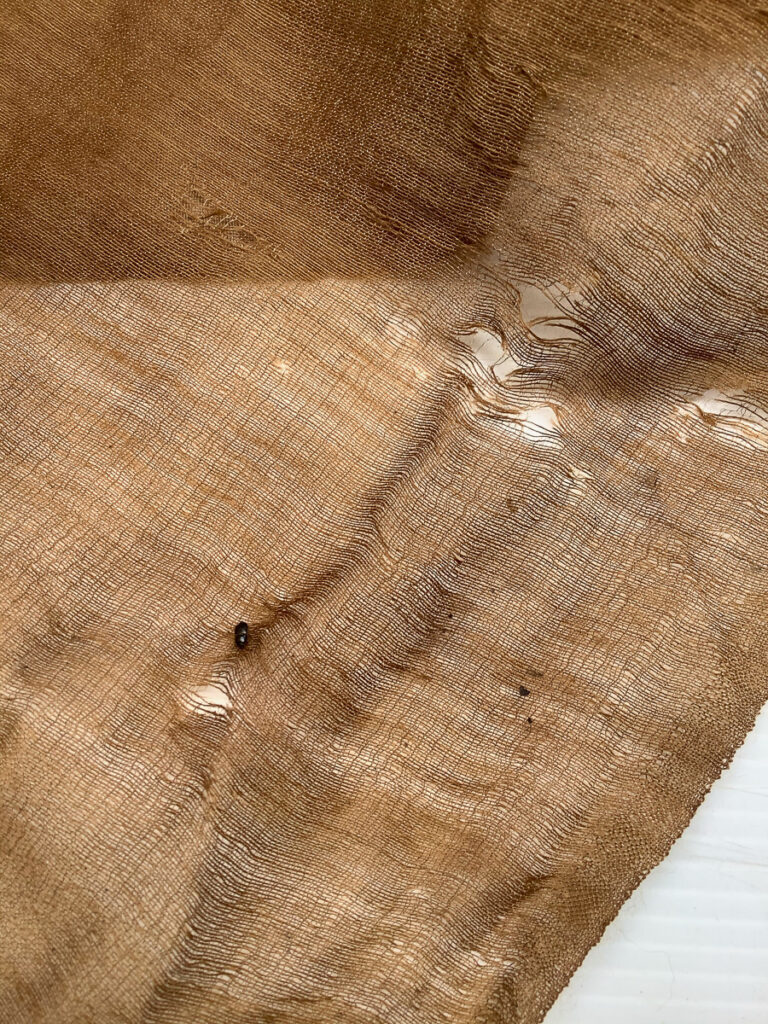

The silk was left for almost eight weeks and I remember almost not being able to find the location of where it was buried. When it was finally found, the fabric was brown and grey in colour but it had also begun to disintegrate and was full of holes, a work of art! Parts of the fabric had disintegrated leaving holes at random places similar to holes created in knitting when you missed a loop.

The afterlife

The idea of working with decaying moulding piles of leaves stems from thoughts of the afterlife. I was raised in a Buddhist household, there was talk of death and the “afterlife”. I found this somewhat terrifying because, in order to be reincarnated into something better in the next life, I have to be an exceptional human in this life!

I won’t be going to heaven and not sure if I believe in the afterlife but it still fascinates me.

Therefore, I want to help objects that are discarded, unloved or dying and aid them in their metamorphosis in this life. What is seen as rubbish and useless to other humans is what I would gather and see if any pattern or pigment can be extracted.

This is also deeply personal. Sometimes I think of the fabric, rusty metal or a leaf as refugees, just like I was and there is life and a whole lot of love if we allow it.

Liquid gold

Each year decaying eucalyptus leaves that have clogged up our roof gutter are collected into a bucket, instead of throwing it in the green waste bin, this is saved for further decay, to be used to dye the finest natural fibres available.

It is also a silent protest against everything around us today that is presented as fresh, new, shiny and perfect.

Decaying gutter leaves is an unpleasant sight for most. There is a smell of the rotting leaves disintegrating as it mixes with rusty metal, rainwater and the air. As the liquid evaporates it begins to look like sludge from a swamp with fear of the unknown lurking beneath.

This sludge is scraped into a bucket to be used as a dye. It is like liquid gold, full of tannins and possibilities for creating colour on cloth. Fabric is stuffed into the bucket and left all winter and in late spring when temperatures rise and fall again, the bucket evaporates and I can dip a paintbrush into the sludge and use it the way batik artists use hot wax to create their patterns before submerging the cloth in boiling dyes.

Most of the plants that I use for dyes are edible or medicinal, this means they are never harmful or toxic unless they are left to ferment and rot. The most interesting colours and patterns form when dyes are left to sit in pots and vats in extreme heat.

Walnut bugs

January is hot in Canberra. The weather reaches forty degrees celsius and the temperature can drop significantly in the evenings. It’s a good climate for growing stone fruit and walnuts.

There is a huge walnut tree in our local neighbourhood where I go to collect all the fallen husks and leaves discarded after the galahs have had their feed. The walnuts are mostly inclosed in the hulls as the galahs bite through to eat the young walnut flesh.

Sometimes, the dyeing process is shared with bugs and insects that aid in the decomposing process in nature. The walnut curculio is a bug that eats away the outer green layer of the walnut hulls. Fabric is placed into the dye bath and the curculio bugs are allowed to eat their way through the cloth, protein fibres ( silk and wool) decompose at a faster rate than cellulose fibres (cotton and linen).

While most people would leave nothing to chance when it comes to natural dyeing, here it is left in the hands of insects and bacteria. The bugs are allowed to dictate the end result of the colour and shape of the cloth. This technique mostly works but sometimes when left too long the entire cloth can completely disintegrate!

Sunburn

Some of my favourite patterns have been created by sunburn when I forget to put the lid back on a pot. The water evaporated and parts of the fabric that was above the liquid became exposed to the sun causing dark crackling sunburnt marks. The first time this happened and I was extremely annoyed because the colour on the fabric should have been even with no marks. When the cloth was pulled out, the lines and patterns caused by the sun were similar to that created by the Japanese Shibori technique of resist and tie-dyeing.

When dye pots are left exposed too long, another decaying process begins. Bacteria, fungus and mould grow on top of the liquid. For me, the fungus is another form of dye as many types of mushrooms can yield colour. The mould growing on the fabric changes the colour or forms unusual patterns that resemble something on a petri dish in a science lab.

The best creations have been invented out of mistakes.

There is beauty and colour in everyday life right in our backyard if we choose to see it.

“In nature nothing is perfect, yet everything is perfect” Alice Walker

About Samorn Sanixay

I am a Lao Australian textile designer and weaver living in Canberra, Australia. I have been dyeing and weaving textiles since 2002 and my greatest passion is working with everything that is leftover or has been discarded by other people. Follow @samorn_sanixay.

I am a Lao Australian textile designer and weaver living in Canberra, Australia. I have been dyeing and weaving textiles since 2002 and my greatest passion is working with everything that is leftover or has been discarded by other people. Follow @samorn_sanixay.

Comments

Your work is beautiful and I love that you are using decaying, changing, moving effects. It is a stirring idea and produces glorious fabrics.