- Triodos Bank Project by RAU Architects

Thomas Rau and Sabine Oberhuber outline a circular model for creating buildings as transient material depots.

Today, for the first time in human history, gold is leaving our supply. Previously, extracted gold was always processed into jewellery or other decorative articles that, due to their value, were always passed on with care or at most remelted. “All the gold that has been mined throughout history is still in existence in the above-ground stock,” says gold expert James Turk. ”That means that if you have a gold watch, some of the gold in that watch could have been mined by the Romans 2,000 years ago.”

According to the British Geological Society, about 12% of the gold mined each year is nowadays processed into electronic devices: the average smartphone contains about 30 mg of gold. The majority of those devices are simply discarded after use, or end up in kitchen drawers—only to turn into waste years later. According to the EPA, Americans alone throw out $60 million worth of gold and silver each year in smartphones. One ton of circuit boards is estimated to contain 40 to 800 times as much gold as one metric ton of ore. Most of this gold is taken out of circulation, and its volume surpasses that of the amount of gold that is mined annually. Our gold supply has thus started diminishing, rather than growing.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the amount of gold on Earth is dwindling, of course: we just lose access to it. When we talk about losing things in this way, we are talking about “losing” in a relational sense: these things are lost to us. They of course do not vanish into thin air. “What exists is uncreated and imperishable, for it is whole and unchanging and complete. It was not, nor shall it be different, since it is now, all at once, one and continuous,” as the Greek philosopher Parmenides said.

The material passport

Our socioeconomic world has become so complex that, with all the goodwill there is, we still could never be sure that nothing gets lost—unless we write everything down. Only by “catching” our physical world in data can we organise finite resources in such a way that they remain accessible to us permanently.

Think of the way a library works: through the process of documenting who borrows which book when, books remain accessible generation after generation. Every book has an identity—a symbol—which, in its physical absence, represents it within the confines of a well-ordered system. This permanent identity allows for the library to keep track of the whereabouts of their books, so that it isn’t necessary for the library to keep the books on the shelf at all times. Instead, its book collection is always spread out over the shelves, backpacks, cars, workplaces, and nightstands of its various members.

Following the same principle, we came up with the material passport: a document containing a detailed inventory of all the materials, resources, and components of a product or building, as well as detailed information about their location—providing materials with identities that are independent of their current use.

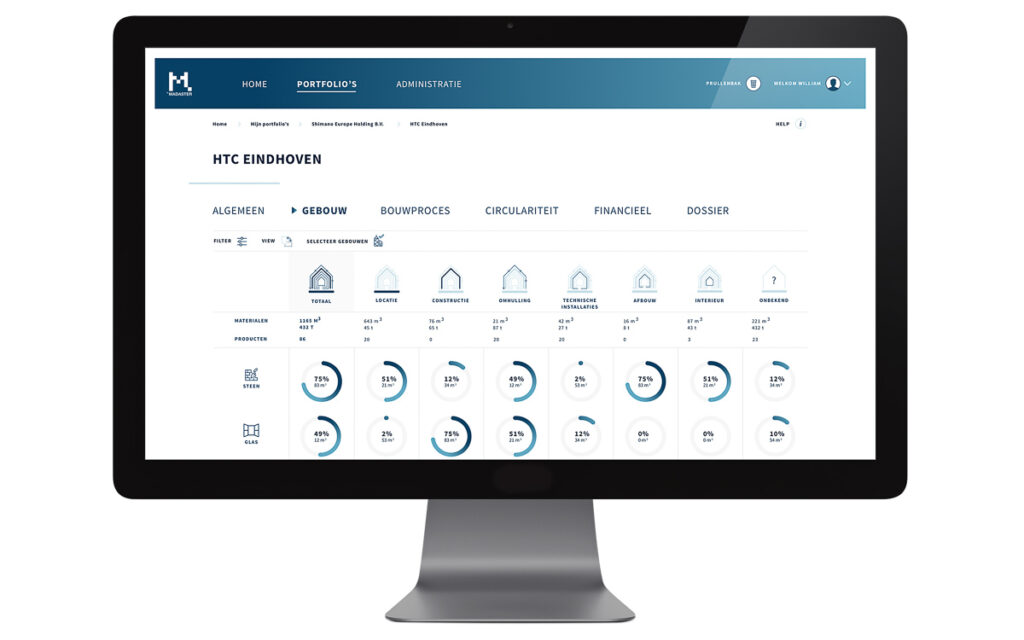

How would an economy in which materials have independent identities work, exactly? That is easiest to explain if we take the construction industry as an example—not an insignificant sector in terms of resource consumption. It uses around 40% of all resources, worldwide. Even if this were the only sector we could convince to use our material passport, the effects would be unprecedented. For that reason—and because of our background—the construction sector is where we have begun putting our theory into practice first. We started by developing a 3D-BIM (Building Information Model), which functions as a material passport in the world of buildings. In this material passport, all information about the materials is registered, documented, and saved. This includes an extensive description of which materials were used in a building, how much of each material was used and which modifications the materials have undergone. Every part, no matter how small, is documented in this way—protecting it from drifting and ending up as waste. To make it easy to create and store such a passport we created an online platform called Madaster, the cadastre, or land registry of materials.

Buildings as Material Mines

Providing every new building with a material passport allows us to make a lot of progress: approximately 40% of the buildings expected to exist in 2050, have yet to be built. However, if we can take stock of the resources and materials used for the construction of all existing buildings, the effect would be even bigger. If we can develop a sense of respect for supposedly worthless, depreciated buildings, these building will turn into an interesting source of value.

At the present time, someone who needs to get rid of an existing building goes about this by calling a demolition firm and getting out their credit card. If that person is in possession of a material passport, however, their depreciated building suddenly gains value again, meaning they might not have to pay for the demolition at all—and in some cases might even make money from it! This principle applies to all buildings, everywhere in the world. We call this principle: “Buildings as Material Mines”.

To give you an example of this: we were recently approached by a large company, and were asked to help them solve something they were struggling with: they needed to get rid of an enormous building on their property. In one of the following meetings, we routinely asked how much money would be gained by demolishing this building.

“Gained?” they replied, confused. “The demolition costs us €1.5 million!”

Since the building had been depreciated down to zero book-value, the company had automatically assumed that it had become entirely worthless. It was not, of course.

To prove them wrong, we spent the next two weeks “mapping” the building as a mine: we identified all the materials used, took stock of them, and estimated their value. We ended up identifying about €600,000 in materials value, which our client still could capitalise.

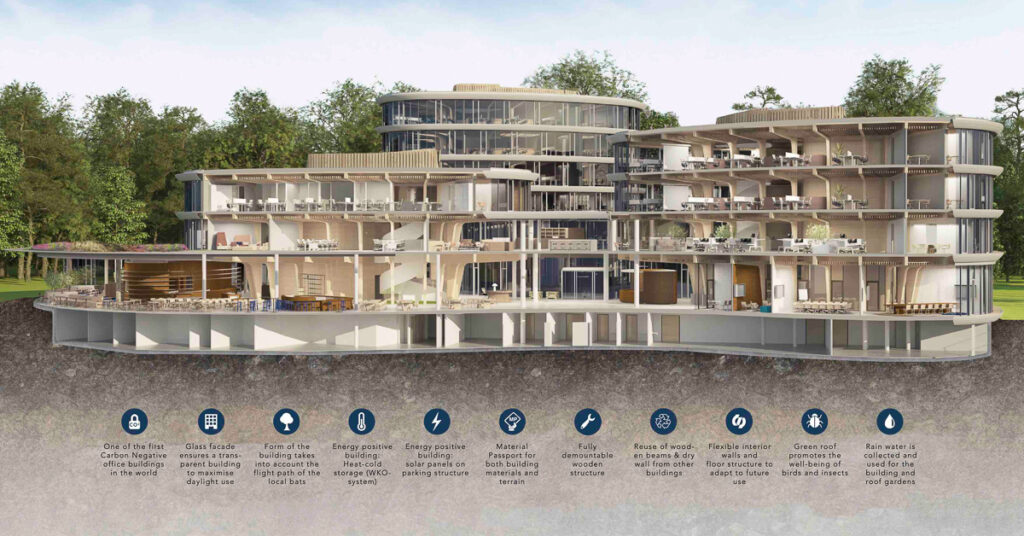

Buildings as Material Depots

- Triodos Bank Project by RAU Architects, photo: RAU Architects

- Triodos Bank Project by RAU Architects, photo: Ossip Duivenbode

A second way of using material passports follows a principle we refer to as the Buildings as Material Depots principle. When a building is designed in a way that materials can be taken out again, it automatically turns into a kind of depot for materials: a storage of resources, kept safe for future use. As we explained above, every building is in essence a material depot, however unorganised—unless we knock it down the minute it stops fulfilling our temporary need. However, the difference between mine and depot is determined by the amount of thinking ahead: buildings that were built for disassembly and equipped with material passport in hand are depots, buildings that were built without these qualities are mines.

Obviously, material depots are many times more efficient than material mines— even beside the fact that we know what’s in them, and where everything is located and how to retrieve it. After all, if we register the materials and resources that will go into a building before it has been built, we can use this information to influence the design and construction process, thus ensuring that all materials can easily and safely be taken out of the building at some point—without losing any of their value. This will give rise to a whole new market of reusable products, components, and materials that make building, renovating, and dismantling buildings as easy as possible.

Buildings as material banks

As soon as we see that buildings are in essence material depots, we can take things even further: we can stop depreciating buildings to zero, as is dictated by the logic of our current economic model. In the Turntoo model, the value of buildings will be written down, rather than written off.

If we not only register the location of specific materials, but also estimate and register their value, we can turn a building into a kind of ‘material bank’. The conserved material value of a building (the sum of the value of all resources temporarily stored inside it) can amount to up to fifteen to twenty percent of the total cost invested in constructing the building. Its real economic value may end up being much higher than that, of course—time will tell. The rest (labour, energy) is lost, but those are unlimited resources, meaning we will always be able to replace them. Our limited resources, on the other hand, should be treated with utmost care.

An important condition with regards to conserving value is, again, that buildings must be designed and constructed in ways that make it easy, and therefore economically worthwhile, to dismantle them and reuse the materials and resources stored in them. This will translate into a financial incentive for developers, producers, and builders to anticipate temporality right from the start.

Buildings as Material Depots or Banks is the guiding principle for projects we realise with our studio RAU architects. In 2012 RAU Architects was asked to design the headquarter of Triodos Bank the most sustainable bank in the world according to the Financial Times. With this project, the most advanced application of a building as a materials bank has been put into practice for the first time. Every resource and material used for its construction was registered in a material passport, and its design allows for every component to be “harvested” at all times—without losing any of its value. The financial value of all material is known to the bank and a team of accountants is working to make these materials “bankable”.

This is a slightly adapted extract from the book Material Matters, by Thomas Rau & Sabine Oberhuber, which has been published in the Netherlands in 2016 by Betram en de Leeuw. The book was published in Dutch, German and Italian and will be published in English language in 2021.

A light at the end of the cave

Ted van den Bergh, former director of Triodos Foundation (the bank’s charity department) shares a diary entry about working in the Triodos Bank building:

“It was a cold rainy morning and quite early that day, when I entered the building for the first time. In the middle of construction work, my first impression was that of entering a cave: dark, wet, chilly. On the naked floor, tools and pools of water. But when we walked on, we were surrounded by huge wooden structures, the core of the building. It was like being a tiny creature looking up to an enormous toadstool. We had a wonderful view of what was once going to be a field of green again. Construction workers told us how astonished they were at first about what they were supposed to build, and how proud it made them now this revolution was unfolding. The part we were in now was overwhelming, the spacious room, the curves, the light. I started to love this place.

“Months later we started to work in this amazing office. I felt like coming home. The initial cave turned into a sea of light, warm colours, wooden and woollen floors. We got lost in a world of different spaces, small, big, open, closed, never ever the same. In the beginning, it was impossible not to get lost. The natural warm and silent atmosphere made me feel relaxed. Only problem was: this was not my home, I was supposed to work here! After a short while the office was a home-like workplace, a superb place to focus, but in a relaxed way, or to have fruitful conversations with colleagues or customers, enjoying the view and the inspiring meeting rooms. This building is a showcase for sustainable development and a heavenly place to work. It made me proud and happy to host visitors.”

About Thomas Rau and Sabine Oberhuber

Thomas Rau is an architect, entrepreneur, innovator and recognised thought leader on sustainability and circular economy. His office RAU has been recognised for being at the forefront of producing innovative CO2 neutral, energy positive and circular buildings as a norm. Thomas was elected as Dutch Architect of the Year 2013 and awarded with the ARC13 Oeuvre Award for his widespread contribution in both promoting and realizing sustainable architecture and bringing awareness of the circular economy through international delivered lectures, TV documentaries, Ted talks and Publications. In 2016 he was nominated for the Circular Economy leadership Award of the World Economic Forum.

Thomas Rau is an architect, entrepreneur, innovator and recognised thought leader on sustainability and circular economy. His office RAU has been recognised for being at the forefront of producing innovative CO2 neutral, energy positive and circular buildings as a norm. Thomas was elected as Dutch Architect of the Year 2013 and awarded with the ARC13 Oeuvre Award for his widespread contribution in both promoting and realizing sustainable architecture and bringing awareness of the circular economy through international delivered lectures, TV documentaries, Ted talks and Publications. In 2016 he was nominated for the Circular Economy leadership Award of the World Economic Forum.

Sabine Rau-Oberhuber, is an economist, together with Thomas Rau she co-founded Turntoo, one of the first companies in the world focusing on the transition to a circular economy. Together with her team at Turntoo she assists companies and institutions in the development and implementation of circular business models and management strategies and facilitates the transition to a circular economy. She studied economics at the Freie Wilhelms University in Münster (Germany) and received her Master of Management from the ESCP (EAP) European School of Management in Paris, Oxford and Berlin. Previously she worked as Corporate Strategist and Manager Internet Strategy in the strategic planning for Reed Business Information.

Sabine Rau-Oberhuber, is an economist, together with Thomas Rau she co-founded Turntoo, one of the first companies in the world focusing on the transition to a circular economy. Together with her team at Turntoo she assists companies and institutions in the development and implementation of circular business models and management strategies and facilitates the transition to a circular economy. She studied economics at the Freie Wilhelms University in Münster (Germany) and received her Master of Management from the ESCP (EAP) European School of Management in Paris, Oxford and Berlin. Previously she worked as Corporate Strategist and Manager Internet Strategy in the strategic planning for Reed Business Information.