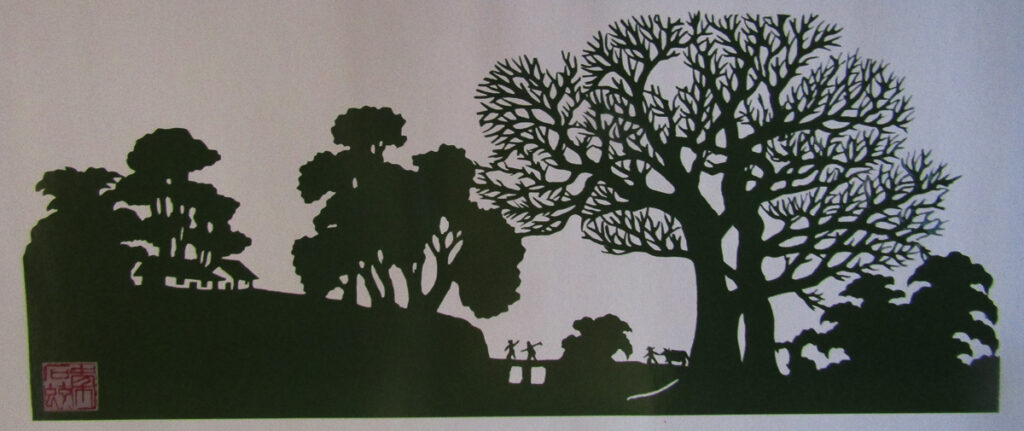

- Ning Yaxiao (2020) Xiaojing Qiaokou, Fishing Capital. Handcut paper. 108×50cm. Image supplied by the Huxia Papercutting Museum.

- An example of Qing Shijiao’s landscapes. Supplied by the artist.

Pamela See charts the evolution of Chinese papercutting from its Daoist roots to the influence of Western landscape.

From Poverty to Prosperity: Landmark Landscape Exhibition at the Huaxia Papercutting Museum in Changsha, Hunan Province, Explores the Rise of a Proletariat and their Visual Language.

Over the past decade and a half, I have observed a transition in the papercuts that line the streets during the Spring Festival or Chinese New Year. Hand-cutting was supplanted by laser-cutting. Paper has been replaced with plastic. In addition to the methods of mechanical reproduction, I witnessed the position of papercutting evolve from folk to high art. Irrespective, they continue to play an integral role in this most significant of calendar observances.

Introduction: From Craft to Art

Xu Mingxing, The First Miao Village Targeted Poverty Alleviation, 2020, Handcut Paper. 60×65; supplied by the Huaxia Papercutting Museum

During the Year of the Rat, a digitally manufactured plastic cut out was fastened to a window in the renowned papermaking village of Shiqiao in Guizhou province. In Shaanxi province, from which both paper and papercutting originate, hand-cut and laser-cut versions of papercuts were sold by the same vendors. On 17 October 2020, for the seventh National Poverty Reduction Day, the Huaxia Papercutting Museum in Changsha, in Hunan province, opened an exhibition of landscape papercuts. Landscapes also took pride of place in the Guangling Papercutting Art Museum and Vocational School in Shanxi province. It opened with the support of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2007. This elevation of papercutters from artisans to artists by the PRC is reminiscent of the initiatives of Huizhong during the twelfth century. The Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 CE) emperor, opened the Imperial Painting Academy. Amongst the categories of painting, landscape was the most highly revered.

From the Background to Foreground

According to Professor Zhang Daoyi at the South-East University of Nanjing, papercutting artisans also emerged during the Song Dynasty. In his seminal The Art of Chinese Papercuts, published in 1989, he stated that a “majority of papercut artist are, of course, peasant women…”. The designs were classified by function such as “smoke vent” as opposed to themes such as “bird and flower” or “architectural”. Two decades onwards, in an article in The Chinese Journal of Art, Zhang categorised papercutting into the last of the “four virtues” or domestic work.

The Confucius principles of 三從四德 or “Three Obediences, Four Virtues” emerged during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). It was not until the late Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE) that the patriarchy relented, enabling a selection of women to paint. This minority included the descendants of painters, such as the daughter of a landscape painter Wen Shu. An exception was also made for concubines and prostitutes. They were specifically trained in the arts to entertain scholars and government officials. This was exemplified by the paintings of Ma Shouzhen, who was a prostitute of the scholar Wang Zhideng.

However, Dr Crystal Hui-Shu Yang from the University of North Dakota concurred with Zhang stating in her 2012 article in Notes in the History of Art,

While Chinese calligraphy reflects the intellectual culture, paternal tradition, and written history, papercutting represents the illiterate culture, the maternal tradition and oral history.

Although both Chinese landscape painting and papercutting were informed by Confucius and Taoist principles, landscape painters expressed a need for non-action or to yield to the power of nature and papercutters sought to evoke it. Silk manuscripts of both the 道德经 or the Tao te Ching and 已经 or the I Ching, were unearthed from the 马王堆 or Mawangdui Tombs in Changsha between 1972-74. These texts informed the development of Confucianism and Taoism during the Zhou Dynasty. Whereas “water” features heavily in the Tao de Ching, “mountains” are a significant symbol in the I Ching.

In the seventy-eight chapter of the Tao de Ching, Laozi wrote:

天下莫柔弱于水,而攻堅強者莫之能勝,以其無以易之。

弱之勝強,柔之勝剛,天下莫不知,莫能行。

Nothing under heaven is weaker than water.

Yet nothing however proficient in attacking the strong can win over water.

The reason is that nothing can lay a handle on water.

The weak overcomes the strong;

The soft overcomes the hard.

All under heaven know about this dictum

but few people can put it into practice.

In chapter sixty-six, he specifically references water in the landscape as a metaphor:

江海所以能為百谷王者,以其善下之,故能為百谷王。

The reason why the great rivers and the seas can claim

to be the kings of the hundred valleys

is that they lie low,

so the water in all valleys come to them.

Chinese landscape painting became eponymously referred to as 山水 or “mountain water” during the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE). However, that its origins are shared with the doctrine that informed it is a prevalent belief amongst art historians. An adjunct professor of the University of North Carolina, Sherman E Lee, cited the first examples of landscapes included a “thin-shelled bronze ewer reputedly from Cha’ng Sha in South China” from the “Late Chou period”. The British Art Historian Michael Sullivan concurred, specifying that “pre-Han” landscapes depicted on a square piece of cloth and on a bronze ladle had also been unearthed from Hunan province.

In the Birth of Chinese Landscape Painting in China, Sullivan wrote:

In this period Chinese artists and craftsmen were already strongly inclined towards representing landscape wherever there was the least excuse to do so. Indeed, while the craftsman of classical Europe or ancient India intuitively filled a space to be decorated with human figures, animals, or plant forms, his Chinese counterpart thought first of a landscape…

The oldest example of a cutout, hewn into gold foil dated between the late-Shang Dynasty and the early Spring-Autumn period of the Zhou Dynasty, loosely meets Sullivan’s description. The first historical record of a cutout, a portrait of Lady Li, fashioned from hemp parchment during the Han Dynasty (206BCE – 220CE) does not. However, both the Sun and Bird Foil and the portrait were created a significant distance from Hunan province, in Sichuan province and Shaanxi province respectively. Notably, the purported inventor of modern pulp strained paper, Cai Lun, was born in Hunan but worked and was subsequently buried in Shaanxi Province.

Emperor Wudi of the Western Han had been an avid follower of the Yellow Thearch, a cult of immortality which would also become incorporated in Taoism alongside shamanistic practices of his time. Papercuts, like Lady Li’s likeness, function like “fu” talismans. This aspect of Taoism is described by Claude Levi-Strauss in Totemism as magico-religious. The figures are deliberately devoid of ground. The illustrations or flora and fauna are intended to influence the landscapes into which they are inserted. For example, a papercut of a rooster is thought to bring protection to a dwelling.

From Bird and Flower to Landscape

It is difficult to discern when 窗花 window flowers, which are similar to bird and flower paintings, may have evolved from totemic arrangements into landscapes. However, this evolution was evident in the papercuts endorsed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It is apparent in the development of nationally acclaimed papercutter 蔡兰英 or Cai Lanying. Born in Hebei Province in 1918, Cai documented several decades of her life using scissors. She joined the CCP in 1944 and later became the head of the Women’s Federation in her village. She is best known for her depictions of rural life. Autobiographical, the compositions also documented her family life including a dispute with her husband. In 1996, Lanying was acknowledged by UNESCO as a “Master of Folk Arts.”

Between 1970 and 1971, a set of Chinese papercuts documenting the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s was produced by an art institution in Foshan, Guangdong Province. They included “complete” dioramas illustrating historical occurrences such as young people joining the “Red Guard” and the destruction of “The Four Olds: Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Customs”. The formal training of papercutters and the publishing of reproductions of their papercuts occurred during the 1980s Folk Art Revival. Manchurian papercut artist, Hou Yumei, was educated at the Lu Xun Academy of Arts between 1985 and 1987. Her papercut illustrations of traditions such as “searching for ginseng” included fully articulated landscapes.

Irrespective of the catalyst, landscapes were documented as an attribute of papercutting from Heilongjiang by Dr Yu-Chun Huang in her doctoral dissertation The Origin, Classification and Evolution of Chinese Papercutting. Published in 2012, it examined forty of the sixty-two categories of Chinese papercutting to be awarded the status of Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO and the PRC between 2006 and 2009. However, the papercuts from many other regions feature landscape conventions including Jiangsu province, Guangdong province and the autonomous region of Inner Mongolia.

From Song to Renaissance Realism

The founder of The Huaxia Papercutting Museum, master papercutter Qin Shixuan or 秦石蛟, is renowned for his landscapes. There is a tranquil simplicity in his compositions that reflect the “Three Teachings” or 三敎 of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism. The advocates of these “pillars” of Chinese philosophy shared a relatively harmonious coexistence between the Sui (581–618 CE) and Qing Dynasties (1644 – 1912 CE). In Qin’s landscapes, the longevity of humanity and its architecture is emphasised. Natural elements that have a sustained existence, such as large trees and mountains, dominate the compositions. This principle may be interpreted in the context of “impermanence” in Buddhism or “wu wei” in Confucianism and Taoism.

An example of landscape by Southern Song (1125-1279 CE) Master Painter, Ma Yuan, titled Walking in Path in Spring. Image sourced from Wikimedia Commons, “File:Ma Yuan Walking on Path in Spring.jpg”, accessed 15 February, 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ma_Yuan_Walking_on_Path_in_Spring.jpg.

The approach is also a signature of Southern Song Master Painter Ma Yuan, who is regarded as a bridge between Song Dynasty realism and the literati painting that would dominate the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 CE). According to the Metropolitan Museum, the fourth generation court painter and “leading artist” in the painting academy in Hangzhou:

…moves us from a keen awareness of our descriptive world into the contemplation of our place in the cos[mos]…

Like the literati, Qin also places emphasis on internal realities and this is reflected by favouring abstraction and expressiveness over accurate representation.

The Yuan Dynasty resulted from the invasion of China by the Mongols under the leadership of the grandson of Genghis Khan, Kublai. The occupiers endorsed the realist styles of court, bird and flower painting. Landscape painting became the primary vehicle for the literati who were barred from public service. The brushwork became increasingly abstract and expressionistic as they sought to cultivate “mindscape[s]”. Literati painting would become what is broadly recognised as traditional Chinese landscape. It emerged as an extension of neo-Confucianism during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). It took a foreign incursion to meld the cultural practice to the psyche of the Chinese people.

Literati “write” their pictures as opposed to “draw” or “paint” them.

“Literati” is a plural for the social strata. A singular scholar is regarded as a “literatus”. A majority of literati painters, from the Tang to Yuan dynasties, were scholars without formal art training. The compositions were monochromatic as colour delighted the eye and distracted the mind. For all intents and purposes, the images were considered an extension to calligraphic text. Literati “write” their pictures as opposed to “draw” or “paint” them. Although Qin does employ a limited colour palette, applied using layers, not unlike registered woodblock prints, a majority of papercuts produced in China remain monochromatic. Papercutting skills are still shared between generations of families. Papercutters are now also trained in both vocational schools and universities. The coverage in the Chinese media of the papercutting landscape exhibition at the Huaxia Papercutting Museum indicates that papercutters are given as much reverence as their painting counterparts by the CCP.

The other artists in 金山银山,美丽家乡, which translates into “Gold Mountain, Silver Mountain, Beautiful Hometown”, drew inspiration from a myriad of painting traditions. The title refers to a geographic belt in Western Hunan province. During the lead-up to the exhibition, a group of around a dozen papercutters were given a tour of the region’s villages, mountains and farmland. Some made preliminary sketches using pencils and paper. However, they did not participate in the plein air styled of art production which rose to prominence in nineteenth-century Europe.

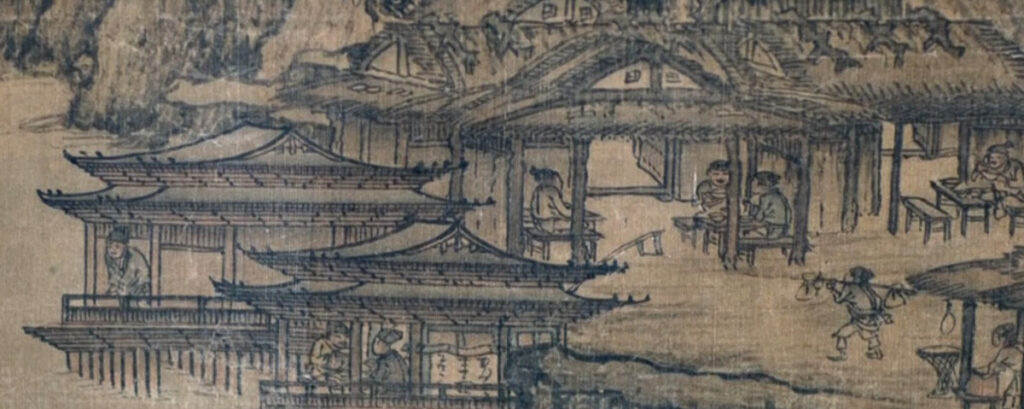

Some of the artists represented villages in a 界画 or “jiehua” style reminiscent of late Tang Dynasty painter Wei Xian, Northern Song Dynasty painter Li Cheng and the Ming Dynasty painter Qiu Ying. Emphasis was placed on the accuracy of the representation of “boundaries” or “architecture”. In some of the papercut landscapes 高遠 or “height distance” was observed. Height distance is one of the three devices propositioned Northern Song Master Guo Xi. The other two are 深遠 or “depth distance” and平遠 or “level distance”. The principle of three distances revolved around the vantage point of the viewer.

A detail from a 界画or “jiehua” by Southern Song Dynasty Master Painter Li Cheng. Image sourced from Plinius, “Picturing Paradise,” some Landscape, 21 April, 2018, accessed 15 February, 2021, https://some-landscapes.blogspot.com/2018/04/picturing-paradise.html.

The painters of the time also communicated depth using atmospheric perspective, which entails dimming the colour of forms in the distance. Perspective, by way of changing the scale of objects and figures, was also prevalent during the Tang and Song Dynasties. However, European linear perspective was introduced to China alongside chiaroscuro during the early nineteenth century. In 1715, the Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione arrived in Beijing at the age of 27. He became a court painter for Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty known by the Chinese name of 郎世寧.

During the 1950s, the painting style of social realism was introduced to China at the behest of the CCP through cultural exchange with the Soviet Union. Chinese artists were sent for “retraining” and academics were received to teach in Chinese art academies. The visiting academics included the award-winning Soviet painter Konstantin Maksimov, who arrived in Beijing in 1955.

One of the papercutters in the exhibition carefully a constructed landscape within a window, which is a distinct characteristic of fifteenth-century Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck. The fish drying in the windowsill of Ning Yaxiao’s papercut, symbolising fiscal prosperity, is comparable to the lavish interiors of its European counterpart. Each plane, the interior and exterior, has its own vanishing point. Whereas optics developed in the early Renaissance to service god, the exhibition was designed to celebrate the achievements of the CCP.

In this exhibition, which celebrates the elevation of peasants out of poverty, there is also a series of papercut tableaux. The artist Xu Mingxing has embraced two other European rhetorics to give the figures authority. The framing with text is reminiscent of Christian illuminated manuscripts, which were prevalent in Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The positioning of the portraits as figures in the foreground of a landscape, over which they have dominion, is a troupe that similarly flourished during the Renaissance.

- Jan Van Eyck, The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (1433-34) Wood, 66x62cm. Image sourced from Wikipedia, “Nicholas Rolin,” 15 February, 2020, accessed 15 February, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolas_Rolin.

- Manuscript page made from The Book of Hours c. 1440. Image sourced from University of Dayton, “Mary in Miniature: Books of Hours in the Marian Library Collection,” accessed 16 February, 2021. https://udayton.edu/imri/mary/b/books-of-hours-exhibit.php

- Examples of papercut portraits with landscapes in their backgrounds from the exhibition 金山银山,美丽家乡。Image sourced from 掌上长沙, “剪纸艺术描绘脱贫攻“, 长沙晚报网, 17 October, 2020, accessed 20 December, 2020, https://www.icswb.com/h/153/20201017/680614.html?fbclid=IwAR207zRZA9GjHG-CP0OYl_PmrHZ7EjfJAqn_PmX-GI6U1o2Wvau1zwLH1sM.

- Example of some of the landscapes in Gold Mountain, Silver Mountain, Beautiful Hometown. Photograph supplied by the Huaxia Papercutting Museum

Conclusion: From Adaptability to Self-Reliance

According to Chinese folklore, as interpreted by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, The Year of the Rat is associated with “adaptivity” and “problem-solving”. The 2020 iteration was characterised by these attributions. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, “reliab[ility]” and “fair[ness]” affiliated with the Year of the Ox is highly anticipated.

It is through binary opposition, which is prevalent in “Three Teachings” or 三敎 principles, that the strength and self-reliance of the Chinese people are celebrated. 金山银山,美丽家乡 or “Gold Mountain, Silver Mountain, Beautiful Home Town” brings together the cornerstone of imperial Chinese culture, landscape, with a favoured medium of the proletariat, and subsequently government of modern China, papercutting.

This twenty-first-century iteration of an ancient craft has been infused with a diversity of rhetorics to explore the theme of the elevation of peasants out of poverty. Authority is given to the people who populate the papercut compositions through references to European Renaissance landscapes, portraiture and illuminate manuscripts. However, the most powerful artworks in the exhibition draw their inspiration from Chinese landscape painting which predates its European counterpart. This includes both the eponymous 山水or “mountain water” and 界画 or architectural styles.

“From Poverty to Prosperity: Landmark Landscape Exhibition” was at the Huaxia Papercutting Museum in Changsha, Hunan Province

Further reading

Artsy. “Piero Della Francesca.” Accessed 20 December, 2020.

“The Art of Qiu Ying.” Asian Art Newspaper, 28 February, 2020. Accessed 20 December, 2020.

Büttner, N., and R. Stockman. Landscape Painting: A History. Abbeville Press, 2006.

Cahill, James. “ Lecture 4B – Tang Dynasty Landscape Painting.” In A Pure and Remote View: Visualizing Early Chinese Landscape Painting.” UC Berkeley Events. Youtube. 1:11:19. Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Cahill, James. “Lecture 8a: Nobelmen Painters of Late Song Dynasty.” A Pure and Remote View: Visualizing Early Chinese Landscape Painting. UC Berkley Events. Youtube. 1:04. Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Cahill, James. “11a – Great Masters of Southern Song: Ma Yuan.” In A Pure and Remote View: Visualizing Early Chinese Landscape Painting.” UC Berkeley Events. Youtube. 1:36. Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Casey, Edward S. Representing Place : Landscape Painting and Maps. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Chen, Y. Women in Chinese Martial Arts Films of the New Millennium: Narrative Analyses and Gender Politics. Lexington Books, 2012.

Chengdu Jinsha Yi Zhi Bo Wu Guan. The Jinsha Site. 1st ed. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, 2006.

CGTN. “Guangling Paper-Cutting Wins Worldwide Recognition.”24 November, 2017. Accessed 20 December, 2020.

Cohn-Sherbok, P.D., and V.R.C. Lewis. Sensible Religion. Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014.

Department of Asian Art. “Landscape Painting in Chinese Art.” The Metropolitan Museum. October, 2004. Accessed 22 October, 2020.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Cai Lun.” Accessed 22 December, 2020.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Illuminated Manuscript,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 21 August, 2019, accessed 20 December, 2020,

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Jinbi Shanshui” Encyclopaedia Britannica. 6 September, 2002. Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Ehret-Kump, Matthew. “The Passion of Giuseppe Castiglione.” Los Angeles Review of Books. 17 January, 2019. 20 December, 2020.

Flitsch, Mareile. “Papercut Stories of the Manchu Woman Artist Hou Yumei.” Asian Folklore Studies 58 (2000): 353 – 375.

Geus, Martijn. “China Projections.” ArchDaily. 9 March, 2019. Accessed 20 December, 2020.

Ho, Lok Sang. The Living Dao: The Art and Way of Living a Rich and Truthful Life . Lingnan University, 2002.

Huang, Yu-Chun. “The Origin, Classification and Evolution of Chinese Paper Cutting.” University of Leeds, 2014.

Jiang, C. Poetry-Painting Affinity as Intersemiotic Translation: A Cognitive Stylistic Study of Landscape Representation in Wang Wei’s Poetry and Its Translation. Springer Singapore, 2020.

Lee, Lily Xiao Hong. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women the Twentieth Century 1912–2000 (Chinese Edition). edited by 蕭 虹. Revised, Chinese language edition ed.: Sydney University Press, 2016.

Lee, S.E. Chinese Landscape Painting. Icon, 1977.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Totemism. Penguin, 1969.

Mathematical Institute of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. “The Yang-Yin Symbol Surrounded by Eight I Ching Trigrams.” Accessed 20 December, 2020.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Scholar Viewing a Waterfall.” Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Nadeau, R.L. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Chinese Religions. Wiley, 2012.

Plinius. “Picturing Paradise.” some Landscape .21 April, 2018. Accessed 15 February 2021.

The Press Library, Library. “Stalin Is Like a Fairytale Sycamore Tree – Stalin as a Symbol.” The Personality Cult of Stalin in Soviet Posters, 1929–1953. The Australian National University. 21 December, 2020.

Sullivan, Michael. “Art in China since 1949.” The China Quarterly, no. 159 (1999): 712-22.

Sullivan, M. The Birth of Landscape Painting in China. University of California Press, 1962.

Sullivan, M. Symbols of Eternity: The Art of Landscape Painting in China. Stanford University Press, 1973.

Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. The Culture & Civilization of China. edited by Richard M. Barnhart New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Tseng, L.L. Picturing Heaven in Early China. Brill, 2020.

Redmond, G. The I Ching (Book of Changes): A Critical Translation of the Ancient Text. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

University of Dayton. “Mary in Miniature: Books of Hours in the Marian Library Collection.” Accessed 16 February, 2021.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Chinese Zodiac: The Year of the Rat.” Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Chinese Zodiac: The Year of the Ox.” Accessed 21 December, 2020.

Waring, Luke. “Writing and Materiality in the Three Han Dynasty Tombs at Mawangdui.” PhD Dissertation, Princeton University, 2019.

Watt, J.C.Y., M.K. Hearn, Metropolitan Museum of Art, D.P. Leidy, Z.J. Sun, J. Guy, and J. Denney. The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010.

Weinberger, Eliot. “What Is the I Ching.” The New York Review of Books China Archive. 25 February, 2016. Accesed 20 December 2020.

Wen, B. The Tao of Craft: Fu Talismans and Casting Sigils in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition. North Atlantic Books, 2016.

Wikipedia. “Nicholas Rolin.” 15 February, 2020. Accessed 15 February, 2021.

Wikimedia Commons. “File:Ma Yuan Walking on Path in Spring.jpg.” Accessed 15 February, 2020.

Wikimedia Commons. “File:Piero della Francesca 044.jpg.” Accessed 15 February, 2021.

Yang, Crystal Hui-Shu. “Cross-Cultural Experiences through an Exhibition in China and Switzerland: “The Art of Paper-Cutting: East Meets West”.” Notes in the History of Art 31, no. 3 (2012): 29-35.

Zhang, Daoyi. The Art of Chinese Papercuts. Traditional Chinese Arts and Culture. 1st ed. Beijing, China: Foreign Languages Press, 1989.

Zhang, Daoyi. “Zhang Daoyi: I’m the Cornerstone of Chinese Art.” Chinese Journal of Art Studies. 6 September, 2019. Accessed 20 December, 2020.

Zheng, Wang. “New Discovery Sheds New Light on Chinese Cultural Revolution.” University of Michigan News Service. 1 November, 2011. Youtube Video, 5:22.

点购收藏网,.”中国剪纸(二)大版“. 3 March, 2020. Accessed 20 December, 2020.

掌上长沙, “剪纸艺术描绘脱贫攻“, 长沙晚报网, 17 October, 2020, accessed 20 December, 2020.

黄卓鹏, 胡琳 和. “华夏剪纸博物馆新馆试开馆 市民可免费参观.” 望城区融媒体中心.. 28 August, 2019. Accessed 20 December, 2020.

About Pamela See

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling) has a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) from Griffith University and a Master of Business, majoring in public relations, from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). In addition to regularly contributing to Garland Magazine, she has also written articles for M/C Journal, Art Education Australia and 716 Craft Design. Her research interests include: craft, post-digitalism, Asian art, public art and participatory art.

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling) has a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) from Griffith University and a Master of Business, majoring in public relations, from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). In addition to regularly contributing to Garland Magazine, she has also written articles for M/C Journal, Art Education Australia and 716 Craft Design. Her research interests include: craft, post-digitalism, Asian art, public art and participatory art.