“Painters, embroiderers and other craftsmen and women leave behind artefacts which future generations can enjoy. But gardens are as fragile as a cloud-bolstered sunset.” T. R. Garnett

[robo-gallery id=”2216″]The garden appears in many cultures as an idyll of lost connection with nature. The Biblical Eden, the English Arcadia and the Persian

The garden appears in many cultures as an idyll of lost connection with nature. The Biblical Eden, the English Arcadia and the Persian charbagh (paradise) have inspired great works of literature, art and craft. While such gardens are necessarily of the past, their cultural representations offer us a path back to what they represent.

Each generation defines this lost garden as the antithesis of its own malaise. And today? If we look back one or two generations, what forms of life have been lost that we might seek to recover?

Instagram has just overtaken Twitter with 400 million users. According to recent statistics, the average user spends more than six hours a month on Instagram. However, the average number of followers who interact with any one person’s post is only 3%. And how much time is spent with each image? More than a second would be generous.

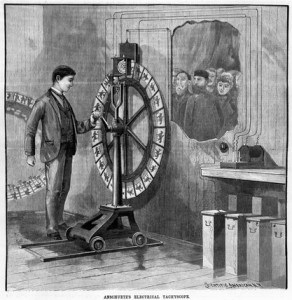

“More is less” seems to be the underlying principle of social media. The ability to scan increasingly large swathes of social activity is predicated on ever declining portions. Blog posts become 140 character tweets become Facebook LOLs become Instagram :-). We see the world through a tachyscope.

While an exhilarating horizontal swathe of information, it is harder to find vertical dimension of time. The august visual arts critic Robert Hughes was an advocate of the ‘long look’ when encountering a worthy painting.

With the Quarterly essay, Garland invests in a writer who has the skills and commitment to hold back time for us. In this issue, Gopika Nath provides a personal account of the Phulkari embroidery tradition from the Punjab. Her writing offers a taste of what craft means in India today. She covers textile traditions around which cultures have formed. Her essay features major historical shifts (Partition), personal journey and spirited contemporary craft revival. The connecting thread is the sublime work of embroidery.

Nath’s essay guides us as we journey to Adelaide, which despite its dryness is a fertile soil for objects of meaning and beauty. Melinda Rackham writes about the Traditional Crafts program by Guildhouse, which features embroidery. And from the other gender, artist Daniel Connell shares a project that explores the meaning of the turban for Punjabi men.

In this issue we introduce two new features to help “tell the stories behind what we make”. Our partnership with Workshops of the World introduces us to the “spaces behind what we make”—the collectives whose camaraderie inspires a history of great art, everyday products and commissions. And to reflect the way in which objects can connect people together, we look at the Craft Classic, including the chain of designer, maker and user that enables it to exist. These developments reflect the impact of the JamFactory as producer, exhibitor and teacher of generations. We hear some of its philosophy from head of the ceramics workshop, Damon Moon. Susan Luckman reflects on why South Australia has such a strong craft ecology.

This issue coincides with the Adelaide Biennial, which is the foremost regular survey of Australian art. As Garland tells the stories of objects in the world, the profiles of artists reflect the craft dimension of their practice. This involves the making process (Heather B. Swann and Jacqui Stockdale) and the traditions with which they engage (Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Louise Haselton). Given the broad readership of Garland, we also look at what’s being produced in the locations that have inspired artists, in this case South Sulawesi and Nagaland. This is also reflected in Tessa Laird’s plaintive letter to the Mexican artisan whose figurine inspired an art work. Jess Dare translates her hands on experience with the Thai garland into works of contemporary jewellery that have a place in Western culture.

You’ll also find Susan Cochrane’s essay about Pacific art in the Asia Pacific Triennial and Frances Potter’s account of basketry exchange between India and Ghana. Finally there’s the Second Home online exhibition, featuring work made from discarded shelters, like shells.

Enjoy travelling back up the garden path. Take your time.

Cover image by Jacqui Stockdale