The challenge is to reproduce a belt woven in 1863 that belongs to the Church of San Francisco Tutla. This mission is fulfilled by Eustacia Antonio Mendoza, a Zapotec woman who is native of Santo Tomás Jalieza, at the end of 2017. In the process, what is recovered is not only the design of a forgotten pattern, but also the memories of two Oaxacan towns. This is an account of the El Señor de Lázaro belt, a strip woven in a backstrap loom that recounts lives of the weavers of Jalieza and the devotees of Tutla. It is an object, among many, with a wonderful story to tell.

Abigail Mendoza tied my waist for the first time to a loom and from there, to one of the columns of the Textile Museum in the city of Oaxaca. Since then, my navel was linked with magenta threads to the earth and she became my teacher. The ability to weave other possible worlds on small canvases is the confirmation of the existence of diverse ways of being that coexist, with each other, in a pluricultural country like Mexico. Years later, Abigail would tell me briefly that her mother had replicated an old sash, thus recovering a graphic pattern that, in Jalieza, had been forgotten. Her approach, with the hope of documenting the event and giving an account of the textile identity that her people have maintained for hundreds of years, is the motive of the small ethnographic research that I present here.

Undoubtedly, textiles protect knowledge, some of it familiar and so much of it hidden in the depth of intertwined wefts and warps. This space allows us to approach, through those who create them, a story that begins to weave. For this, I will talk about the Mendoza women, the town where they live, their workshop and work as artisans. In a second part, I will briefly introduce some references to the Christ of Lazarus in Tutla, and then tie them both in a third scenario that introduces our cultural object: the girdle. Later, I will discover an engraved stone that opens questions about materiality, memory, and cultural identities.

From my job as an anthropologist interested in the expressions and textile dynamics of the Oaxacan people, it is an obligatory task to point out the influences and confluences that sociocultural events like this one give us, since they constitute reflections of cultural memories that are written today as evidence of ongoing relationships between tradition and modernity.

Las Mendoza: Artisans of Jalieza

It is midday, the sun falls on the patio of the Mendoza family. Eustacia or Doña Tacha, as she is called affectionately, weaves a ribbon that will be applied to the shirt of her grandson. Between the play of comb, yoke, shuttle, machete and threads, she advances with the skill that only someone who has been weaving since the age of six, can have. Meanwhile, Veronica, her youngest daughter, does not let the sewing machine pedal stop and Abigail approaches a wooden bench to join the conversation while her long black hair continues to dry in the cool air. All these Mendoza, daughters of Doña Tacha, weave. Each one has a specialty and they all take family work out of the workshop. The father also wove and the paternal aunt named Maria, who lives with them, is an authentic authority of the loom. María and Tacha, as the most experienced, are the stalwarts who stick more to the traditional, following the well-known count of 21 threads in their creations. Abigail, who is also a celebrated woman in her craft, weaves very thin pieces that are legendary. Noemí and Eva do it in the same way and Verónica also knows how to weave, design and sew. They have all mastered the traditional counts of 5, 11, 21, 25 and 45 threads, but they also innovate in their creations.

They all live in Santo Tomás Jalieza, a town 25 km away from the capital of the state, belonging to the district of Ocotlán, region of Valles Centrales in Oaxaca. Although recognised as a town of weavers, its name, Jalieza, seems to derive from the Zapotec xana (below) and lieza (church) meaning “under the church” or also, according to other versions could mean “extract the earth.” Regardless of this, the truth is that the current life of the people takes place in courtyards and corridors where women and men of different ages tie their waists to looms and columns to create delicate pieces full of colour and charm that make up a textile craft that distinguishes them from other towns.

Doña Tacha recalls with laughter, the smacks her mother gave her if she could not get the fabric right. She stresses that, when someone starts knitting, the important thing is to make a very simple design while paying special attention that the edge is very straight. There one begins to master the art and technique known as labrado de urdimbre, wrought warp.

Thus, from a very early age, lying on the floor, with no mathematics to guide her designs, without drawing on paper, just counting threads and experimenting, Tacha weaves threads making thoughtful images emerge and preserving stories. All her daughters learned the trade very early and Veronica, the youngest, began at age four copying her sisters. Therefore, the way in which these women relate to the loom is vital and immediate.

In the words of Abigail: “The loom is part of you. You stay with it and there live your feelings. It shapes how you are at a certain moment. You also release your sight, your lungs, your muscles. We can notice the spirit that the person who made a textile because of the way it is made and the colours used.”

It is evident that, in the loom, memories are captured. When it is not by commission, weaving becomes a creative, personal and unique act. The Mendoza say that it is something that relaxes them when it is done for pleasure, when it is theirs. Weaving is by far Tacha’s favourite activity. She prefers it before anything else. She spends much time weaving in the same position and can at the same time, be aware of everything that happens in the family yard. With Abigail, we see the opposite. She prefers weaving while sitting on a chair and it is much better working when under pressure. Each “artisan”, as they prefer to call themselves, is different, as are the relationships they establish with their looms.

Sometimes, Tacha dreams that she weaves beautiful things and this makes her want to create them. She says that when she weaves she does not copy other artisans, but she does take ideas. Her daughters annoy her, saying that she likes to always do the same kind of things, but she argues that each piece is different, even though she prefers certain colours and figures. The range of colours includes cherry, black and beige and, although they encourage it to change from time to time, she always returns to the same tones, always including beige.

The Mendoza have been weaving with fine threads for a long time, since Aunt Maria in the seventies visited the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico and saw some strips woven with thinner threads than those normally used in the town. That is why thereafter they were perfected in the fine wire technique. They make bags, small and large girdles, backpacks, purses and other pieces that respond not only to the pursuit of a tradition but to the demands of the current market. They have learned to combine their textiles with other materials such as leather bags and later they started making the famous loom backpacks that became an artisanal boom.

Although it seems a structured and well thought-out trade, it provides great freedom. Many times they do not know what they are going to do until they sit down to do it. On occasion, they can weave amidst the surrounding of great activity and noise and others not. The bracelets are, for example, more automatic, because as Abigail says, they do them with extreme skill and cadence no matter what happens around. On the other hand, when it comes to a new design, they like to be alone, to concentrate. If someone gives opinions or ideas they are distracted and interrupt the process. Therefore, when necessary, the weaver is left alone with her loom to do what she wants.

A few months ago, Abigail wove something new for a contest. She started drawing and every time she tried to start knitting, she could not succeed. Time passed and it was up to a day before the delivery when she managed to realise the design. She did it all at once. As it was a new and complicated piece, she had to concentrate and be inspired very well to get it out. She was in a very bad mood, assured her relatives.

On the contrary, Doña Tacha never draws. She resorts to her imagination, visualises it and weaves it little by little. She prefers to do it slowly, because the time pressure worries her and makes her nervous.

Good mood is an important part of the fabric because the threads can feel. If they perceive otherwise, they can become entangled or refuse to fulfil a design. Hence, the emotion can affect the threads in the piece. If in the end, they feel proud of their work, judging it as beautiful and well made, there is no doubt that there was also love. On the other hand, if they feel bad, they know that the fabric will be difficult to weave. When this happens, it is better to stop everything and return once you find enough desire. With the commissions it happens differently. Then the emotion of both parties is involved, the good or bad connection is difficult to overcome. In each attempt, the loom and instruments are asked to work well together.

Cotton threads dyed naturally or not, and threads of other materials, have always been used. It is known that red and cherry are colours that prevailed in ancient textiles and this tonality was acquired with the use of cochineal. Previously the threads were made in the community. It is said that when people started weaving, they were few and they met in one place with subsequent trips to other places to sell their product. Mainly women ventured out and took three directions: Tlacolula, Oaxaca and Guatemala. When they walked towards the latter, they travelled with a row of donkeys and while they were leaving the town they rang the bells. Let’s say they left early in case something happened on the road and they could not get back alive. At that time, Maria points out that it was just muleteers and difficult roads.

We remain seated on the patio as the sun rises. Tacha unravels her work in order to re-weave it. The sun warms our heads and with it grows the doubt of whether the loom and the sashes came from elsewhere. Then Maria comments:

I believe that it originated in our lands and although they say that we come from Guatemala, it is better to presume we took it there. There is much argument, all will have something of the truth. It is part of how a reality is becoming and transforming. Unlike Teotitlán, where it is known that the loom came with the conquest, in Jalieza doubt remains. Before there was a market, the women gathered to knit and when the tourists arrived they hid because they did not speak Spanish and they felt awkward to talk. Now, on the contrary, almost nobody speaks Zapotec.

Weaving is the common denominator shared by being Jalieza’s people, so they say: “We all do it in the community, but not all of them do it outside of it.”

A scarred Christ: The Lord of Lazarus in Tutla

And he that was dead came forth, bound hand and foot with graveclothes: and his face was bound about with a napkin. Jesus saith unto them, Loose him, and let him go.

(John 11:44)

Oh, I thought; How many times the genie

thus sleeps in the depths of the soul,

and a voice like Lazarus waits

for him to say, “Get up and walk!”

Gustavo Adolfo Béquer

There is no doubt that Sunday is a good day when you want to visit a Church. It is assumed that the doors will be wide open and that someone will be there to answer any questions. However, it does not always happen that way. Due to the earthquakes that occurred in Mexico last September 2017, the church of Tutla, like many others in the state of Oaxaca, is closed waiting to be repaired. The damage is not so alarming, but in any case, they are not allowed to perform mass inside, which is why a chapel has been improvised where the liturgical offices are carried out. Therefore, the image of the Christ that carried the girdle was not visible to us. However, I went with the authorities from the municipality who very kindly opened the temple, allowing me to contemplate the image for a few minutes.

The town of San Francisco Tutla is just twenty minutes from the capital of the state and its political-social organisation, like that of Santo Tomás Jalieza, is based on “internal normative systems” previously called “uses and customs” and therefore the political authorities interfere in religious matters and vice versa.

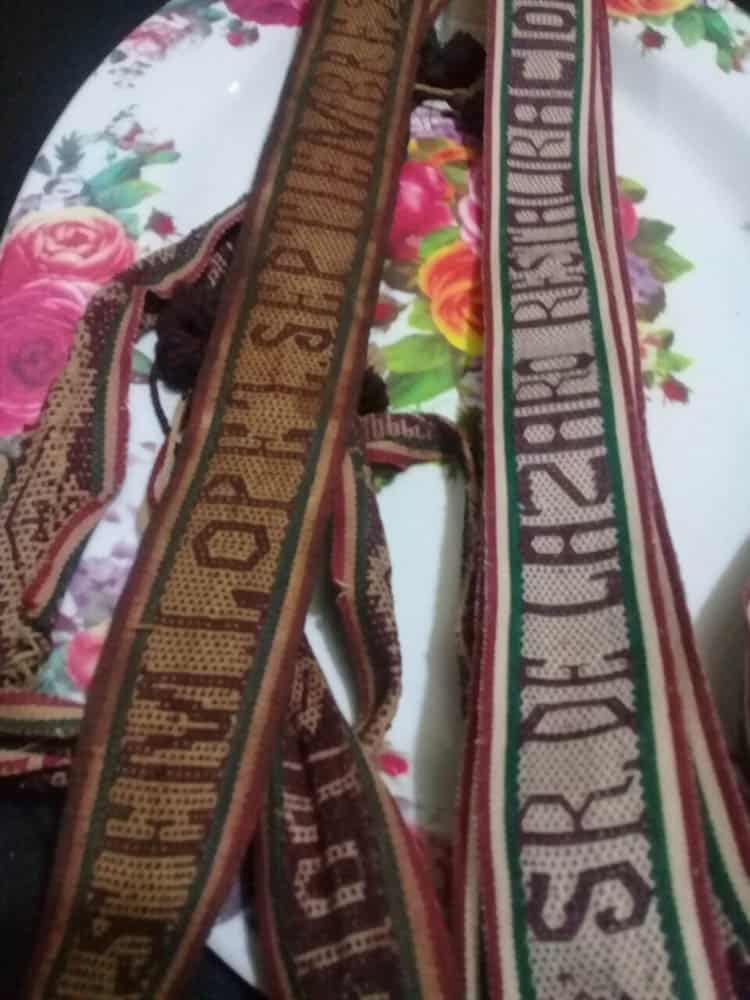

A crucified Jesus Christ with the title of the Señor de Lázaro is venerated in that locality. Well hung in the largest niche on the left side of the nave of the church and behind a glass, it rests (if you could say so) hanging accompanied by flowers, ornaments and a white cloth hanging from the cross drawn with various motifs. There is the surprising presence of a thin woven strip that surrounds the torso at chest height where followed by a fret interspersed with tiny stars, it reads head-on: SR. DE LAZARO RESTAURACION 2017, a legend carved with a combination of cherry, beige and green colours.

Without being the patron saint of the people, the El Cristo de Lázaro or Señor de Lázaro, as he is sometimes called, is extremely helpful. He is solicited for healing by both sick and well people. The Resurrection of Lazaro de Betania is represented in two annual celebrations in Tutla. One takes place the first days of January around the celebration of the “Sweet Name”, when the image is transferred to the main altar and, the other, on the Sunday after the celebration of the fifth Friday of Lent, where he goes to visit the people accompanying the Nazarene and the Virgen de la Soledad.

The miraculous image is followed by faithful devotees from other parts of Oaxaca, led each year by a steward in charge of the aforementioned festivities. In the same way, they count on a custodian of personal effects who protects the original belt. The image of the Christ who is venerated corresponds, as in many churches, to that of the crucified one. However, although he is prostrate on the cross, he represents the Jesus who during his public life made the miracle of resurrection to Lazarus. That moment when, after several days, Jesus calls him from the tomb and when leaving unties his bandages and shrouds in order to resume life. It is ironic then that Christ himself is bound with a single object: the girdle.

Replicating a traditional fabric more than 150 years old

JOSÉ M. LÓPEZ 22 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 1863 read the belt that, one afternoon in December, Tacha held in her hands agreeing to replicate. She did not know what she was getting into, but seeing the indecipherable pattern contained on the sash prompted the “yes” that she gave in response to the people from Tutla.

It turns out that, in the year of 2017, the Señor de Lázaro’s steward wanted to give a new belt to the Christ as a sign of his commitment. The image had recently been restored and, therefore, it was thought that the sash could also be replaced by a new one in order to preserve the original in a good condition. So, the then mayor of Tutla entrusted Gabriela Antonio Alonso, an inhabitant of the agency, who had family in the town of Jalieza, to help contact the right craftswomen to do the work that the steward wanted to commission. It was known that that old belt came from that town and that today they were still weaving strips of that style. In mid-December, the people of Tutla visited Jalieza in search of the best weaver to replicate the piece and that is how they found the Mendoza workshop.

From the first moment, there was something that all the Mendoza noticed: they had never embroidered that pattern in their workshop and they had not seen it woven in other workshops of the town as far as their memory went. From the outset, they found it very difficult to achieve that task for two great reasons. Firstly, they had been given only a week to do the work and second that it was a design they did not know and had to learn afresh.

But this did not deter them. When they were asked who could make the piece, they all agreed that it would undoubtedly be Tacha as a great repository of traditional weaving; while Vero and the other daughters would support with the count of threads, possible drawings, finishes and other necessities that the work implied. Tacha, as if swallowing large skeins, paused a moment and then agreed to comply with the assignment, accepting loudly the commitment to the majordomos in a timely manner. Today she confesses that the challenge, while it excited her, entailed a daunting effort on her part. Seeing the girdle caused her mixed feelings: a fear of not being able to achieve the task and determination to attempt it. She asked the Señor de Lázaro for strength and devoted herself fully to the task. She spent the first hours fixated on that ancient sash made of thin, shiny threads.

It is believed that the man who made the original belt was from Jalieza and that his name was José María López as recorded by the piece. His name is there and, although it may also be that he has donated it and that is why his name was put, it is an unlikely hypothesis because it is known that only whoever weaves something includes their name. It seems that some of the descendants of the late José María lived in Tutla and that is why the belt arrived there as a gift, but unquestionably the strip was made in Jalieza with the technique used in the town since always, as the pattern is similar to the ones they currently weave. The date inscribed is striking because it is not customary to include any date except the date when something is drawn up. This reveals two interesting aspects: both the antiquity of more than 150 years of the piece and the presence of a design then used and whose use was discontinued or replaced without leaving any apparent record.

In terms of the raw material used, Abigail ensures that the yarn is very fine, a blend of silk and cotton. The thread is difficult to weave because it is slippery, which makes the belt soft and light at the same time. Something that caught her attention was the brightness and the absence of fading in the colour. The shades of cherry, beige and green are still perfect.

Doña Tacha recalls having rescued a few years ago the design of a woman who went to the countryside carrying her baby with an old textile and she recorded the pattern. Proud of her designs, she developed a large sample book in shades of pale pink and blue, where she has almost all the figures she weaves in her textiles as a woven memory. In it there are all kinds of figures, such as insects, flowers and representations of people. Some of the anthropomorphic figures make or carry something, such as the woman who goes to the countryside to give water to men, or who is carrying a baby. There are differences between how they dress one another. One wears an elaborate costume while the other has a simpler dress, which speaks of different moments and activities of the everyday life of Jalieza.

Many designs recall myths such as the siren, which was brought by the Spaniards and is frequently included in many strips. Others include double-headed eagles or pomegranates that are also found within the iconography of the town church. The strips contain references of past and present; traditional iconographies and recent creations. Although sometimes, some of the meanings are forgotten and you can only say that they are part of the tradition, it is still relevant that they continue to play a role in Jalieza’s textile culture.

Replicating that belt entailed, from the beginning, great interest for the Mendoza in terms of history, the type of threads used and the design of a forgotten pattern. Without a doubt, the challenge was great if we add that the original weaving was perfect. The skill of José María provided an inspiration and opportunity for Doña Tacha to show her great skill as an artisan of the threads.

The authorities of Tutla granted special permission for the belt to stay in the workshop of the Mendoza while the replica was woven and a week later, after the agreed deadline for delivery, the steward returned for his order. Tacha worked tirelessly as she remained focused on fulfilling the mission. Deep inside she knew that it was a good thing to do in spite of the required expertise and limited time. After an arduous week of work, she delivered it. A few months after the mission was completed, Tacha notes that making the piece made her feel very good. They said that work touches the heart because the loom can feel. The week after the delivery, Tacha could not walk. Her body was crippled, but she had succeeded.

Carving memories in stones and warps

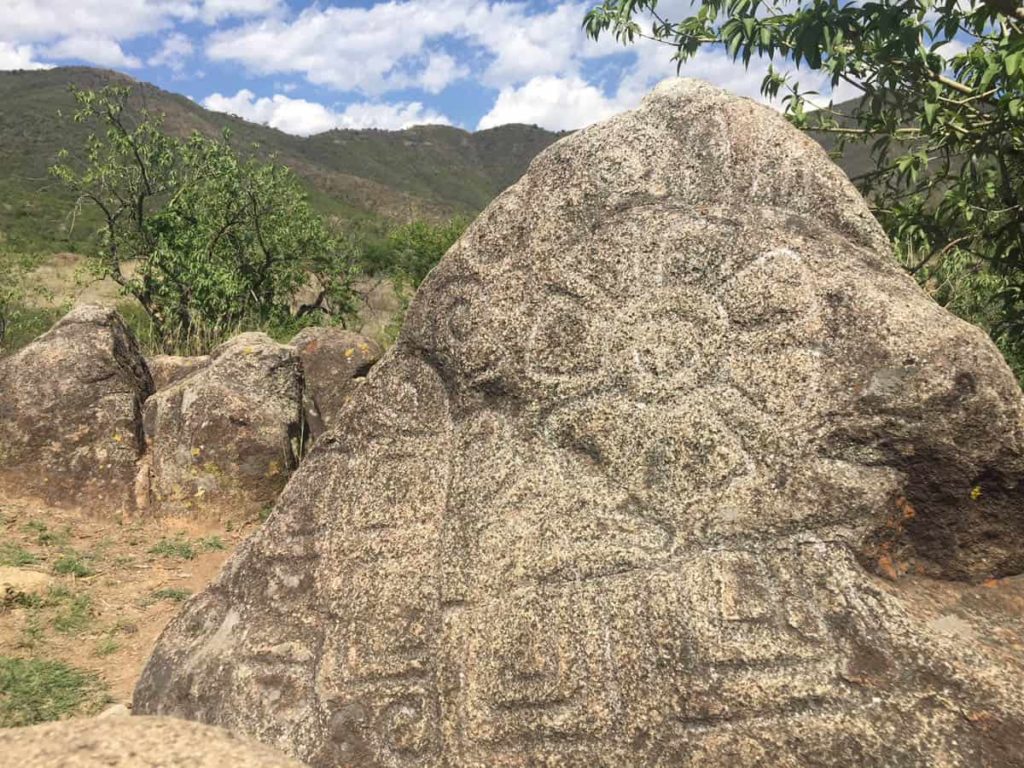

While we talk, the threads Tacha gathers with rhythmic movements quickly become woven designs. She has been absent because now she is tying the threads of her thought. She drops the comb and says that, now you think about it, the fringe of the belt is very similar to the design that can be found on one of three petroglyphs that belong to the community.

If we think of the second possible meaning of Jalieza “to extract the earth”, it seems that something must have happened for its inhabitants to take the earth, in a metaphorical sense, and move to the part of the valley where the current community is located. It is known that before, they lived at the foot of the mountain near a basin where two rivers flowed, in the place known as the Mangalito. There, among green grass, dwells an engraved stone surrounded by hills. As we walk to get closer to it, Abigail tells me that the stone has always been there, sheltered by the intense blue of the sky that protects arid lands. She used to go to school with her classmates and mark the figures they saw in relief while they were told stories of charms and places of wealth hidden beneath them. He tells us that on several occasions they have tried to remove the stone to take it to the village. But far from achieving it, the stone became more entrenched. Next to it there are two others where you can see rough simpler engravings that seem to represent the Orion constellation.

“The stone of the letter” as it is named, shows engravings on three surfaces and according to surveys carried out by archaeologists of the INAH-Oaxaca in 2015. It is a carved stone dating from the Post Classic period (1200-1521 dC), final period of the city-states that are distinguished by the presence of cacicazgos (chiefdoms) just before the Spanish conquest. One of the three faces of the stone reveals a kind of serpent or eel with fins in ascending form and another, a flower or star; both, reasons that could be related to the design present in the 1863 strip.

Without the data that allows me to delve into the cultural context of that stone, it should be understood as a multivocal object related to different sociocultural fields. The reason for attributing the embroidery design to it is the manner in which a people legitimises, through an object, the authenticity and textile identity of which they are carriers. In terms of heritage, this stone serves as a resource that, accompanied by orality, supports the identity of a town of weavers.

Ethnography as a method for finer spinning

A belt contains, ties, supports, binds. It is usually placed in the middle of the body, marking a kind of equator around the waist, sometimes with one or several turns. It is usually worn over other garments and basically serves as an ornament. The strips are part of the traditional clothing of both men and women in many indigenous peoples of Mexico and, in the case presented, constitutes a textile that surrounds the image of a crucified Christ.

It is, in both cases, a garment that envelops. In the cultures of Mexico, “the act of wrapping” is not only manifest in clothing, but also in the culinary, the ritual and events that are an important part of a culture. By this I mean the variety of techniques used to make and wrap tamales, the ways in which food is distributed in a celebration, the ways of wrapping a newborn, the labour of childbirth or in death, or the turns of a rooster in the air during a healing ritual.

It is evident that culture manifests itself in many ways and a very important one is through the ways of dressing and what we decide is worthy of being dressed. Added to this are the various techniques, materials and other resources used to create a garment. To dress is to wrap the body and forms a fundamental part of daily and festive rituals. Therefore, the Jalieza belt is part of a material culture that demonstrates the use, creation and production of a piece that involves not only waists and Christs, but the ideology of being and belonging to a community of weavers over the different generations. It activates, at its own rhythm, the objects of its culture.

As I mentioned at the beginning, the text presented is a first approach to address and document a fact of relevance for two Oaxacan localities. In the case of Jalieza, the recovery of a pattern from the replica of the belt and its possible relationship with the engraved stone and with it the link to a shared worldview and ritualism among the Zapotecs of the Valles Centrales evokes interesting symbolic contents that sustain and legitimise an enduring textile tradition for this town of weavers. For its part, for the residents of Tutla, the long-standing presence of a woven object that is part of the most important image within its church, also expresses the continuity of a cult that, through generations, remains dynamic between its inhabitants.

Having said that, this embryonic account seeks to establish a useful background for an upcoming in-depth study that considers the importance of restoring the original piece, thereby allowing other culturally relevant elements to come to light and nurture the history of localities involved

Anthropology is a discipline responsible for detailing, through ethnography, the multiplicity of relationships that the human being engages during the process of making a culture. This allows, as with textile artisans, step by step weaving threads in the careful path of knowledge creation. Ethnographic work requires thinking the threads and patiently plotting them up to imagine different ways of understanding social realities that form the unfinished stories of a country as diverse culturally as Mexico.

This work makes anthropologists artisans. We carve meticulously, giving room to the multiple voices that exist to achieve a historical fabric that reflects the most comprehensive memory. Our research is at the service of those who give the image a reality.

Author

María del Carmen Castillo Cisneros, PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Barcelona and research professor at the National Institute of Anthropology and History. Since 2001 she has worked with indigenous peoples in the state of Oaxaca, highlighting her ethnographic work with Tacuate, Mixe, Mixtec and Zapotec peoples. Her PhD thesis on Mixe ritualism received the Fray Bernardino de Sahagún Award in 2015. Currently, she coordinates the Oaxaca team of the National Ethnography Program of the Indigenous Regions of Mexico, directs Cuadernos del Sur, a social science journal and presides over the Advisory Council of the School of Social Sciences of the UDLAP. Amazed by the manifestations of a cultural diversity that surpasses and tries to know, since 2003, she has been living in the city of Oaxaca, where she intersperses the days between anthropology, writing and cooking, three muses that become more interwoven each day in her life. She follows closely the issue of textile plagiarism and is developing an anthropological perspective on the blouse of Tlahuitoltepec.

María del Carmen Castillo Cisneros, PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Barcelona and research professor at the National Institute of Anthropology and History. Since 2001 she has worked with indigenous peoples in the state of Oaxaca, highlighting her ethnographic work with Tacuate, Mixe, Mixtec and Zapotec peoples. Her PhD thesis on Mixe ritualism received the Fray Bernardino de Sahagún Award in 2015. Currently, she coordinates the Oaxaca team of the National Ethnography Program of the Indigenous Regions of Mexico, directs Cuadernos del Sur, a social science journal and presides over the Advisory Council of the School of Social Sciences of the UDLAP. Amazed by the manifestations of a cultural diversity that surpasses and tries to know, since 2003, she has been living in the city of Oaxaca, where she intersperses the days between anthropology, writing and cooking, three muses that become more interwoven each day in her life. She follows closely the issue of textile plagiarism and is developing an anthropological perspective on the blouse of Tlahuitoltepec.