Will Stubbs writes how Gunybi Ganambarr uses leftover building insulation to represent the cycle of life and death in salt and fresh water.

Bark paintings are usually applied on the flat surface of the bark. However, late 2006 saw the first incised bark painting come into Buku-Larrnggay. It was by Gunybi Ganambarr. During the course of 2007, he produced perhaps three more, one of real significance that was shown at Annandale’s Young Guns 2 exhibition. In 2008, he was chosen as a finalist to exhibit at the Xstrata Coal Emerging Indigenous Artist prize. His work consisted of two grand incised bark paintings and three incised hollow logs. He won that prize.

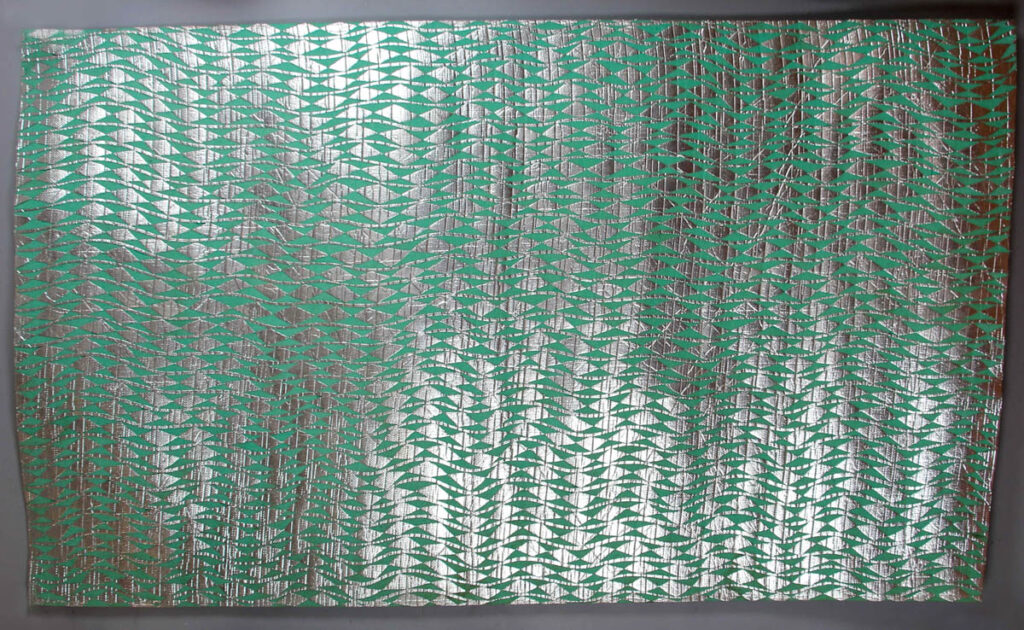

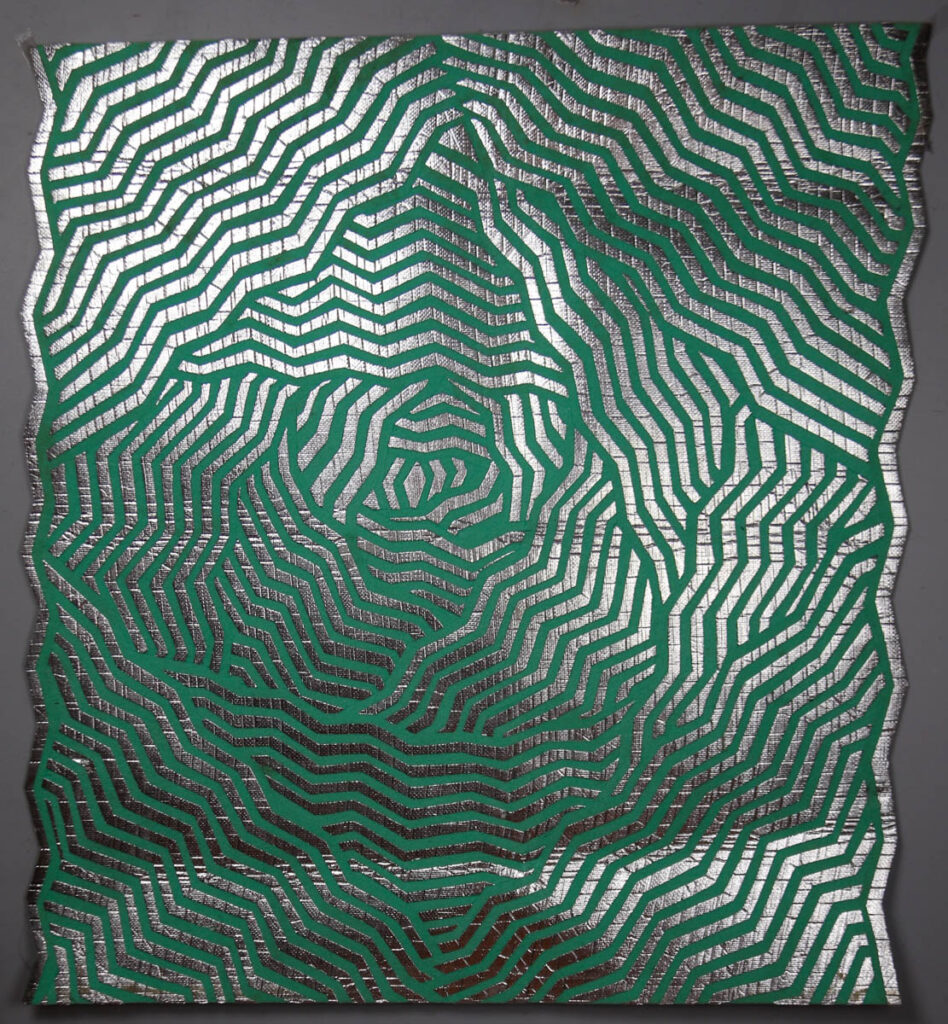

This work is another first for Buku-Larrnggay Mulka. It is part of a series of works made in late 2017 and early 2018 where he incised into foil building insulation which was left by builders at his remote homeland of Gäṉgän. It came about through Gunybi’s incessant desire to experiment with materials. He obeys the long-term stricture from Buku elders “If you are going to paint the land, use the land”, but stretches it to use items that he finds on the land.

“If you are going to paint the land, use the land.”

Artworks of this nature have multiple layers of metaphor and meaning which give lessons about the connections between an individual and specific pieces of country (both land and sea), as well as the connections between various clans, but also explain the forces that act upon and within the environment and the mechanics of a spirit’s path through existence.

Garrapara is a coastal headland and bay area within Blue Mud Bay. It is known on the maps in English as Djalma Bay. It marks the spot of a sacred burial area for the Dhalwangu clan and a site where dispute was formally settled by Makarrata (a trial of ordeal by spear which settled serious grievance and sealed the peace forever). At Garrapara, sacred Casuarina trees held these barbed spears whilst not in use.

During the creation times of the “first mornings” ancestral hunters left the shores of Garrapara in their canoe towards the horizon hunting for turtle. Sacred songs and dance narrate the heroic adventures of these two men as they passed sacred areas, rocks and saw ancestral totems on their way. Their hunting came to grief, with the canoe capsizing and the hunters being drowned. The bodies washed back to the shores of Garrapara with the currents and the tides, as the Wangupini (maternal Thunderhead cumulonimbus cloud) followed with its rain and wind. Their canoe with paddle and their totems Makani (Queenfish), Minyga (Long Tom) and Gärun (Loggerhead Turtle) are all referred to in the songs and landscape.

The Mungurru is deep water that has many states and connects with the sacred waters coming from the land estates by currents and tidal action.

Garrapara has been rendered by the wavy design for Yirritja saltwater in Blue Mud Bay called Mungurru. The Mungurru is deep water that has many states and connects with the sacred waters coming from the land estates by currents and tidal action. This sacred design shows the water of Djalma Bay chopped up by the blustery South Easterlies of the early Dry season.

The miny’tji (sacred clan design) on this piece identifies the Dhalwaŋu saltwater estate of Garrapara on Blue Mud Bay. Here is the sacred site for the Dhalwaŋu Yiŋapuŋapu, a mortuary based sand sculpture used for the initial rites of the dead. The deceased placed within the Yiŋapuŋapu’s elliptical confines has its own contamination kept at bay.

Yingapungapu is used in ritual by the Maŋgalili, Madarrpa and the Dhalwaŋu clans. The detail in its construction identifies particular clan ownership and thus tenure to its particular site, Dhalwaŋu saltwater country at Garrapara, a peninsula within Blue Mud Bay.

A giant tide that capsized the ancestral Hunter’s canoe called Yinikambu washed it back to shore from the waters there out deep, to cleanse the site of Yiŋapuŋapu. The waters then imbued with the deceased’s Dhalwaŋu life force washed back out to the sanctified salt waters of Garrapara.

In the songs, the hooked spears sit under the Mawurraki (Casuarina) trees at the place Bati’wuy and conjure the connections between the ancient mariners and the law of mortuary for Dhalwangu. At the conclusion of the ceremony, participants feast with Yambirrku (Parrot fish) on the ground. Gunyan the sand crab cleanses and renews. It is happening in the distant time before time and also in the present and the far future.

The songs include reference to the maternal Thunderhead cloud Waŋupini and suggest the presence of Nyapiliŋu, the ancestral female being who travelled from Groote Eylandt. The saltwater on the horizon has to metamorphose through a different dimension becoming vapour in order to overcome the obstacle of mortality to be absorbed as life-giving freshwater in the belly of the mother. These clouds then cross the coast and rain life into the hinterland behind the beach which flows down through the rivers to the sea again.

Thus the water traces the spiritual kinship connections of the artist’s identity and leaves a metaphor for the cycle of life. The painting records both of these aspects as well as the political and physical geography of this area. The Makarr or ceremonial spears make this site a centre for dispute resolution.

About Will Stubbs

Will Stubbs worked as a criminal defence advocate in Sydney and the Top End for ten years. In 1995 he married Yolŋu scholar Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr and began working at the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre. He has worked there ever since. In 2015 he was awarded the Australia Council Visual Arts Award for Advocacy. Visit Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, follow @bukuartnow and like Bukuart.