Kia ora, G’day,

Ko Dandenong te mauka,

Ko Yarra te awa,

Ko Port Phillip te whanga

Ko Melbourne te papa tūwhenua

Engari, kei te noho au kei Ōtepoti

The lines above form the beginning of my mihi, the Māori for greeting.

In English they read:

Dandenong is the mountain

Yarra is the river

Port Phillip is the harbour

Melbourne is the birthplace

However, I live in Dunedin

The mihi goes on to describe tribal and family affiliations and near the end you announce your name.

I am not a New Zealand citizen; I am Australian with permanent residency status. Although I look Pākehā (New Zealander of European origin), I choose not to hold this identity. The Māori word for guest is manuhiri. I consider myself a long-term manuhiri. As a craftsperson and an educator, I use this contrived identity to allow a liberty of engagement with Māori culture that is often more difficult for Pākehā.

In 2004, my workplace, Otago Polytechnic, enshrined the Treaty of Waitangi in its educational culture via a Memorandum of Understanding with the three local Māori councils. As part of staff development, all employees of Otago Polytechnic are compelled to attend Treaty of Waitangi Workshops. Initially, these workshops emphasised the sense of guilt for the injustices to Māori that burdens the descendants of the colonists of New Zealand. The net effect was to inhibit engagement with Māori. More recently such workshops focus much more on participation and partnership. Positioning myself as manuhiri (guest) allows me an identity defined by Māori (as is Pākehā), but more distant from that sense of Pākehā guilt or the common feeling of inadequate knowledge about Māori culture.

I have chosen to use this liberty of engagement with Māori as a strategy in my educational practice as well as a way to make sense of why I am an Australian living in New Zealand.

My point of entry into Māori culture was through a course in Te Reo Māori, Māori language. My partner Bron (also Aussie) had just taken on a post-doctoral research project dealing with harakeke (NZ flax). We did Wednesday evening night classes for two years.

Having learnt that I was a jeweller with some jade carving skills, my classmates commissioned me to make a pendant from pounamu (NZ jade) for our tutor Hoani who was a gifted singer and musician.

Part of the language course involved noho marae, an overnight stay on a marae (Māori meeting house) including pōwhiri, the ritual of welcoming guests onto a marae.

I have built this into the curriculum I teach and annually we take jewellery and textile students on a field trip to the Southern end of New Zealand including a noho at Takutai O Te Titi marae at Oraka (Colac Bay). Although my oratory skills are rudimentary at best, I have been able to do the speech-making (kaikorero) for our group of manuhiri.

This year I was commissioned to make a pendant by Rangimaria, who as mana whenua (people of the land) of Oraka, has hosted our group for the past six years. The pendant was for her son Glen. The stone is called Takiwai and is a treasured resource only available to the southernmost of the Māori tribe, Kai Tahu.

An important part of the ritual of welcoming guests onto the meeting house is for the people of that place to extend generous hospitality and care (manaaki) to the visitors. It was an honour for me to reciprocate Rangimaria’s manaaki with my gifted pendant. Rangimaria offered the remainder of the stone I carved to our jewellery department as a koha (gift or donation as an acknowledgement)

I often assume a role of Māori liaison for Dunedin School of Art. This role was supported by the first Kaitohutohu (Māori Adviser) of Otago Polytechnic, Professor Khyla Russell. Building a ten year relationship of trust and respect with Khyla over the past has allowed me access to greater depth of Māori cultural knowledge and with it a responsibility to share that knowledge in accordance with tikaka (the correct way to do things). This trust was manifest in a commission from Khyla to coordinate the making of a touchstone sculpture to be sited at the main entrance to the Polytech’s Dunedin campus.

The key element of the touchstone is a pounamu (New Zealand jade) boulder donated by local Māori elder Huata Holmes. Huata’s words bring together the purpose of the touchstone:

As artists, we perceived our Dunedin Otago Polytechnic and inland complexes as being geologically, educationally and spiritually placed within the influence of the Ocean, Alps and encased between the mouths of our two great rivers. Our stone was chosen to represent all those elements and our presentation was a collective task culminating in its present position to be left unnamed; to beckon passersby, to give or absorb energy latent within the stone.

The pounamu comes from the headwaters of the Dart River that meets the Clutha River & exits to the Pacific Ocean at the Southern edge of the region of Otago. The white stone base is from the limestone country through which the Waitaki River flows, Otago’s northern boundary. The basalt column on which the Pounamu boulder sits is from Blackhead, a volcanic outcrop on the coast very near to the city of Dunedin.

The pounamu comes from the headwaters of the Dart River that meets the Clutha River & exits to the Pacific Ocean at the Southern edge of the region of Otago. The white stone base is from the limestone country through which the Waitaki River flows, Otago’s northern boundary. The basalt column on which the Pounamu boulder sits is from Blackhead, a volcanic outcrop on the coast very near to the city of Dunedin.

The production of the touchstone was a collaboration between Huata, Khyla, myself & three graduate students from Dunedin School of Art (Left to Right); Jennifer Duff (descendent of early Māori tribes; Kati Mamoe, Waitaha & Te Atiawa), Brendon Monson (descendent of one of Dunedin’s first-ship colonists) & Pete Murphy (Kai Tahu). It was appropriate to the work’s purpose that all participants should be from the Polytech. The touchstone was a project that directly integrated both my educational & making practices

Through my recent jewellery work Tiwai Pendant I will trace an increasing material and conceptual responsiveness to locality, mana whenua (Māori people of a location) and the communities to which I now belong.

Scientist, dear friend and near neighbour Dr Barb Anderson (centre, back row) is currently working on a citizen science project Ahi Pepe, in which school children gather data relating to moths endemic to New Zealand. In July of 2017 Barb accompanied four children from Dunedin’s Māori language primary school, Te Kura Kaupapa O Ōtepoti to Toronto, to present the project at the World Indigenous Peoples Conference on Education. Part of the fundraising effort to support the trip included an art auction for which I pledged a jewellery work. The theme for the auctioned work was Kaitiakitanga (being a guardian or the act of stewardship). Kaitiakitanga is integrated with the spiritual, cultural and social life of Māori; is holistic across land and sea; includes people within the concept of environment; is locally defined and exercised; does not focus on ownership, but on authority and responsibility; and is concerned with both sustainability of the environment and the utilisation of its benefits. This word and concept has found a place in contemporary environmental management but its significance runs deep in a Māori worldview.

I have used aluminium extensively in my craft practice but less so as I emphasise principles of material sustainability. There is an aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point near Bluff on the bottom edge of the South Island of New Zealand.

The smelter’s viability is contentious, it uses the entire output from the Manapouri hydroelectric power scheme (13% of the total national electricity production), at an undisclosed (no doubt ridiculously undervalued) cost. The bauxite ore comes from Australia and the smelter is foreign owned by the Rio Tinto company. 800 local jobs are provided by the smelter, buoying the economy of Bluff and nearby Invercargill.

The smelter is sited on a headland that is in the midst of hugely significant archaeological sites where the early Māori found and worked stone for tools. We visit the area during our annual field-trip. The stone that is abundant in that area is argillite or Pakohe, a fine-grained, hard but easily worked material.

Stone from that area was typically used to make adzes (Toki) for working wood. The toki on the left of the following figure is made from argillite sourced nearby the smelter.

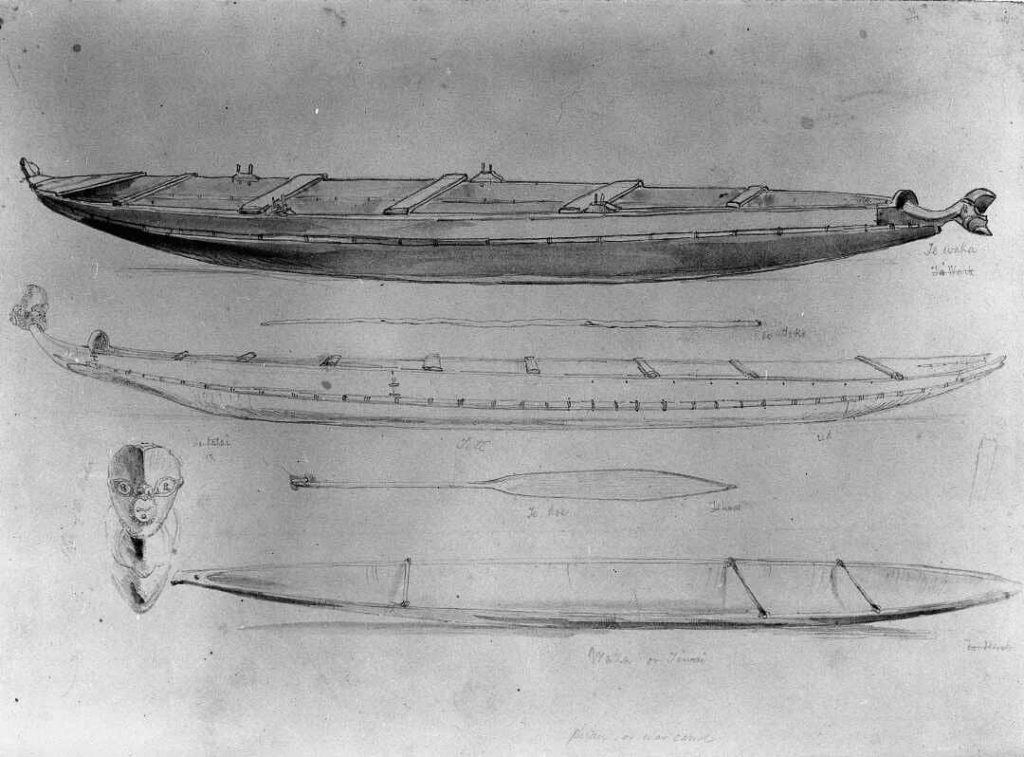

Adzes like these would have been used to build waka tiwai (dugout canoes) after which the smelter location is named.

The tools in this figure were excavated when the building in which the touchstone sculpture is sited was being constructed. Khyla followed on from the touchstone commission and asked me to make a display cabinet for these treasured artefacts (taonga).

In the statement describing my pendant for its presentation at the auction in Otago Museum I borrowed a Māori proverb, (whakatauki ) attributed to the Ngati Mamoe leader, Te Rakitauneke, whose burial place is located on Bluff Hill according to tradition; “Kia pai ai taku titiro ki Te Ara a Kiwa” (“Let me gaze upon Foveaux Strait”).

I can imagine the distress of the leader’s ghost looking toward Foveaux Strait with the industrial complex obscuring a site from which canoes were launched for travel across the Strait to Rakiura (Stewart Island)

Tiwai Pendant is made from aluminium and argillite, both sourced from Tiwai Point. It was purchased at the auction by another dear friend, Harry as a 40th birthday gift for his wife Ruth.

Eight years ago, Harry had asked Ruth’s father for her hand in marriage. Ruth’s folks were delighted and gave Harry a diamond engagement ring that had belonged to Ruth’s great Aunt. Harry asked me to remake the ring using the diamond, gold and adding some component of NZ jade. During a visit to Ruth’s family’s holiday house on Stewart Island Harry faked a stumble and while down on one knee pulled the ring out of his pocket and proposed.

Needless to say his proposal was accepted and my next commission was for a pair of wedding rings.

I had not anticipated that the pendant would end up belonging to Ruth, merely focusing on a material narrative relevant to the theme of stewardship. That the pendant represents layers of connection, meaning and community is a perfect outcome, indeed a fulfilment of what craft and perhaps jewellery does best of all the forms of visual art.

When I migrated to New Zealand in 2001, my colleague Johanna Zellmer (also a recent migrant) and I gave a talk at the NZ contemporary jewellery conference. We commented on the enduring legacy of the Stone, Bone and Shell exhibition from 1988, thirteen years before we presented our talk. The exhibition sought successfully to convey a sense of national identity to NZ contemporary jewellery primarily through the use of materials endemic to NZ. From an Australian and European point of view, it seemed parochial for NZ contemporary jewellers to remain faithful to this constructed national identity. Having now lived in NZ for close to two decades, I have made connections to people and place, I have engaged with Māori people and culture and I’ve made work for and in response to NZ people and place.

I am just now beginning to understand the value of located craft and art.

Building relationships, cultural knowledge and trust with Māori through my educational institution has allowed me to work with treasured cultural materials such as pounamu/NZ jade. As a maker, my work has given me an avenue to reciprocate the hospitality I’ve been extended as a guest and migrant. As an educator, my experience of Māori culture has allowed an insight to a worldview that is other than the dominant European/Western. A worldview that genealogically relates people, land, plants, animals and the spirit world offers a way of being that favours care and protection of the environment. Jewellery’s intimacy and capacity for fostering positive social connection make it an ideal art form for catalysing the change in worldview needed to move toward sustainability.

Perhaps in spite of my constructed identity as visitor or cultural guest my work manifests a sense of belonging, care and reciprocal relationships to the place and people of toku kainga noho—my adopted home.

Author

Andrew is from Melbourne but has lived in Dunedin since 2001. He is a jewellery lecturer in the Dunedin School of Art at Otago Polytechnic, the job that brought him to Aotearoa. Andrew’s art education was at RMIT’s Gold & Silversmithing department and he lectured at Charles Sturt Uni in Wagga for ten years prior to crossing the Tasman. Andrew is a maker of jewellery, sculpture, houses, boats, bikes, bass guitars, bits and bobs. Much of this work goes to friends, family and community, often in a gift economy, occasionally by commission. His recent work is characterised by the relationships between people, place and materials.

Andrew is from Melbourne but has lived in Dunedin since 2001. He is a jewellery lecturer in the Dunedin School of Art at Otago Polytechnic, the job that brought him to Aotearoa. Andrew’s art education was at RMIT’s Gold & Silversmithing department and he lectured at Charles Sturt Uni in Wagga for ten years prior to crossing the Tasman. Andrew is a maker of jewellery, sculpture, houses, boats, bikes, bass guitars, bits and bobs. Much of this work goes to friends, family and community, often in a gift economy, occasionally by commission. His recent work is characterised by the relationships between people, place and materials.