(A message to the reader in Assamese.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

I stepped into the narrow lanes of Kumartuli, to be greeted by a busyness that was hard to define. Small yet frequent workshops seemed to go on endlessly—veering off in many directions, a haphazard maze of mud, straw, and wood—while artisans stoically went about their work. The sculptures seemed to rise out of the earth, few painted with the likeness of the gods, hands and faces of clay baking in the sun.

Kumartuli is the abode of the sculptor. It is the place where life is breathed into deities of Hindu lore – Durga and her children, Ganesha, Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Kartikeya. And no occasion embodies this art better than the annual festival of Durga Puja, when the idols of the goddess are presented in all their glory in embellished pandals all through the city.

- A lane in the colony of Kumartuli, 2018

- An artist working on the embellishments for the deities, 2018

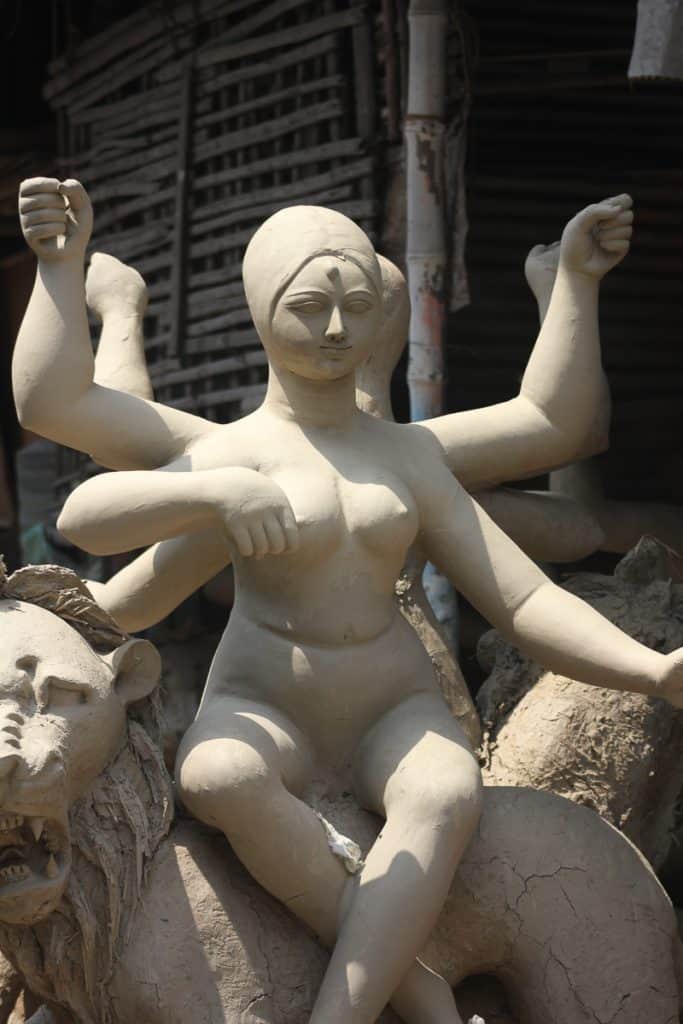

- Sculptures of deities awaiting completion, 2018, sculptures made of clay

- An artisan smoothening the surface of a sculpture of Durga, 2018, sculpture made of clay,

- An artisan painting the eyes of the goddess, 2018, painted sculpture made of clay

- The hands of an artisan shaping the feet of the goddess, 2018, sculpture made of clay

- Fine-tuning the details of a hand, 2018, sculpture made of clay

- A finished sculpture of Durga on her mount, the lion, 2018, sculptures made of clay

- A finished idol of the goddess, 2018, base of the idol made of clay

Walking down the narrow lanes, I came across idols in many different stages of creation. Some were just straw, whereas colour was making an appearance on the bodies of a few other. In one of the workshops, a relatively young artisan was gathering straw into the shape of bodies. I observed the nimble movements of his hands and deduced that this wasn’t the first time that he was doing this. Not wanting to disturb him, I looked around his small, dark workshop. There were some half-finished idols standing towards one side, and a heap of straw on another. Clay rested in large open containers while some partially formed sculptures collected dust in a corner. When the artisan finished making the structure of one idol, I took my chance to ask him about the process of creating these idols.

First, the artisan creates frames of wood, on which straw figures are formed in (the) distinct postures. They are then moulded over with clay. This stage happens in two parts; where first sticky clay and rice husk are spread over the straw structures/figures and left to dry. Once cracks begin to appear on the surface of the idols, a second layer of clay is added, this time with a fine-grained clay, gently and deftly (under the guidance of the practised sculptor) until the surface is smooth and flowing. The faces, hands, and feet of the deities are created separately, requiring more detail, and then attached to the body.

Using tamarind seed paste and water-soluble paints, the bodies are adorned with colour and expression, with each stage demanding adequate time and attention. The utmost care is reserved for the expression on the face of Durga. Only the master craftsman undertakes the task of painting her eyes, the most defining feature of the goddess.

After a thorough coat of varnish, the deities are bedecked with clothes, ornaments, and hair fashioned out of nylon, following which they are finally ready to meet the masses.

I realised what it was that seemed off here—time. It ran paradoxically here, you feel the hurry of the place, but no artisan compromises on the quality of his work. It is more than just sculpting for the occasion of Durga Puja. It is art for the love of it, a story of labour and love, of imagination and creation. Each stage requires care and attention, where every movement of the hand is precise, carried out with purpose, shaping the clay till hand and object are indistinguishable. I noticed how narratives are moulded into each pose, every expression—every movement of the sculptor heavy with purpose, yet free and flowing.

These are the god-makers, gods themselves. They step into the role of the creator, a powerful entity working under the influence of forces invisible to the human eye. Picking up bare, seemingly disparate elements from Nature, the creator brings them together to make something almost otherworldly—gods and goddesses from myth and legend in striking poses, re-enacting stories where they stand proud. The subject of their creation is largely known and much anticipated, but it is in the little nuances, the gestures of the hands, the grace in the faces of the deities, that the vision of the creator comes through.

The riotous celebrations of the Durga Puja, much-awaited, see the deities in their full glory, for that short while before they are given back to Nature. In an elaborate procession on the last day of the festival, the deities are carried to the river to be immersed. Their immersion too is celebrated for it signifies the cycle of life. Shaped from the earth, they are absorbed back by the earth—and then the process starts again.

Author

A nanya Hazarika has been obsessed with stories for as long as she can remember. While anything from her surroundings can pique her interest, she is inherently drawn to histories, creating and creation, and the element of magic. She has lived in different places in India, with Delhi being her latest sojourn. As a storyteller for Kamalan, she identifies and connects stories from various fields, finding ways to share them with the world.

nanya Hazarika has been obsessed with stories for as long as she can remember. While anything from her surroundings can pique her interest, she is inherently drawn to histories, creating and creation, and the element of magic. She has lived in different places in India, with Delhi being her latest sojourn. As a storyteller for Kamalan, she identifies and connects stories from various fields, finding ways to share them with the world.