On a warm April day, I arranged to meet a group of graduate museums and heritage students for lunch at, what had since the 1880s been called “Chinaman’s Dam”, a remnant landscape of alluvial gold mining. It was five kilometres from the rural New South Wales’ town of Young.

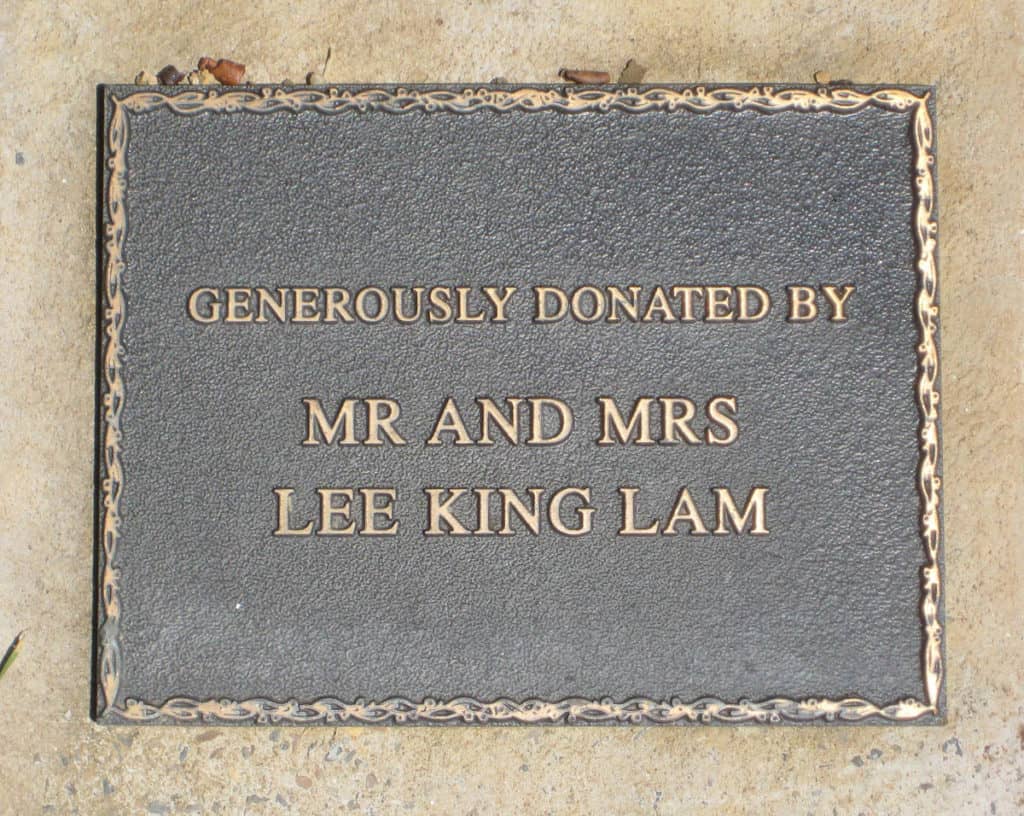

In 1992, the local Rotary Club began re-landscaping this spot, now known as the Chinese Tribute Gardens. At the entrance stood a pair of traditional Chinese Gates which had come from the old panda display at the Taronga Zoo in Sydney. New earthworks created a passive lake and stoneworks were crafted by a local stone mason. They re-fashioned the eroded gullies, mining shafts and water races, helping to construct a new cultural landscape, a peaceful aesthetic backdrop to the “Pool of Tranquillity” where we were to enjoy lunch. The international students were clearly excited to be out in the country for the day. However, other students were quite agitated. Before the food was unpacked, the conversation sharply turned to the morning’s visit to the Lambing Flat Folk Museum (LFFM), focussing on how the violent history of the region had been glanced over in the museum.

Previously I had taken groups of students to the LFFM and the reactions ranged from benign amusement to professional embarrassment at the inexpert displays and labelling. The museum had little external funding and most of their collection was out on display in the converted primary school. Like many other small rural Australian museums, the displays focus on the ordinary and everyday pastoral life and is heavily reliant on volunteers, local historians and donated objects for exhibition.

In bringing students out on the two-hour drive from Canberra, this time I was both a little uncomfortable yet curious. This was the first cohort of Chinese students in heritage and museums studies. While I was hoping to elicit a response to some of the objects and accompanying texts by the Chinese students, I hadn’t anticipated vigorous reaction by the domestic students.

Walking in from the bright sunshine into the dim and quiet building, visitors are confronted in the first gallery by a very large horizontal display case, holding a “destination” object. It is the only exhibit in the museum built to modern museum standards and accompanied by professional labelling. Within the case is a hand-painted banner with circus-like font proclaiming: ROLL UP, ROLL UP, NO CHINESE!

Sensing an uneasy feeling in the domestic students, many of them moved on quickly to other galleries. I anticipated their laughter, as previous students had done, as they walked through the subsequent galleries. In particular, the case displaying stereotypical twentieth-century objects such as dolls dressed in Chinese clothes, a panda, a small Buddha statue and blue and white ceramic teacups. Red Chinese lanterns were strung above in celebration of the Chinese New Year earlier in the year.

The lingering students in the first gallery, studied the banner and the text prepared by Museums New South Wales who funded the display case. They spent time reading the other very long text panels prepared by the museum volunteers. Known as the Lambing Flat Roll Up Banner, it was made in 1861 and was a clarion call for disgruntled Euro-American miners to arms. Yet, Chinese gold miners who arrived in great numbers in the second half of the nineteenth century, and who were violently evicted from the gold fields, have little representation or genuine voice in this institution.

Standing in this museum, it is easy to think of the gold-mining Chinese as, what historian Eric Rolls termed in 1992, “sojourners”: those who came to seek their fortunes subsequently returned to China. More recently historians, such as Keir Reeves, have overturned this simplistic notion. He notes that many did not return to China, or did so after spending the bulk of their lives in settler colonies on the Pacific Rim. The visual analysis of photographs by historian, Sophie Couchman, also points to a more enduring presence of the Chinese in Australia. She notes that we cannot always understand the meanings, functions and intentions of the photographers and the photos they take. Hidden histories can be uncovered, or perhaps recovered through photographs, making them rich resources for museums.

Those with a very keen and active interest in Australian history and politics, visit the LFFM to see this large sheet of canvas, used as a rallying point during the 1861 anti-immigration Lambing Flat Riots. These race riots led directly to the implementation of the New South Wales Chinese Immigration Act 1861 and led to the White Australia Policy (formally known as The Immigration Restriction Act 1901). It was an explicitly racist response towards Chinese immigrants.

The discovery of gold resulted in the trebling of the population of the small Australian colonies. Before the gold rushes, there were under 3,000 Chinese in Australia working as labourers. Once gold fever struck, the population of Chinese increased rapidly and most of the Chinese absconded from their employers.

On the harbourside at Guangdong or Fujian, would the outbound Chinese stepping onto the boats have been aware of how they were to negotiate their own ethnic identities at their destination of the New Gold Mountain? Looking at my own students I wondered about their negotiation of identity as students in Australia.

Initially, as the Chinese men passed through towns along the way, their unusual appearances were “seen as interesting and picturesque.”1.Anne Curthoys (2001) ‘Men of All Nations, Except Chinamen’ in Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook and Andrew Reeves, eds., Europeans and the Chinese on the Goldfields of New South Wales Gold; Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001) :103 The constantly rising numbers caused concern. In the first half of 1857, 14,000 Chinese gold seekers passed through the small seaside town of Robe, South Australia. At the time, an historian of Robe, Kathleen Birmingham, noted that the new arrivals were dressed in “very full jeans, cotton socks and a wool lined blue jumper; wooden sole shoes with uppers of embroidered silk, heavily embroidered, with a round pork-pie hat or in the sun a broad-brimmed one of bamboo fibre with a small crown.” Birmingham noted that it was common, but not a universal practice, that as clothing wore out, the Chinese would change to “moleskins and blue or red shirt of the European diggers.”

One of the key roles that dress plays is to demarcate gender. Here in Australia, Chinese masculinity was expressed markedly different from the white gold diggers. It was not just the appearance of their pigtails, straw hats and embroidered shoes, but also their pole-carrying and their ways of cooking that contrasted starkly with European males on the goldfields. Their lack of women among the population also attracted attention. According to historian Barry McGowan, in 1861, there were only two Chinese women and 12,968 Chinese men in NSW.

There was a lack of government administrators at Lambing Flat: a recipe for disaster. By June of 1860, the first violent anti-Chinese riot erupted. It was the culmination of eight months of growing conflict between Euro-American and the Chinese miners. A long list of causes ranged from racial prejudice to wasteful mining methods, water shortages, fear of economic competition, homosexuality, their practice of taking up abandoned mining claims, to the covert export of gold back to China.

From the Euro-American perspective, the Chinese had very different and very unfamiliar, very complex embodied, social and spatial practices, or what Pierre Bourdieu termed habitus. The bodies of the newly arrived Chinese spoke of their pasts: embodied in ways of walking in wooden shoes, their utterances, carrying their possessions on bamboo poles, their dress practices, their diet, their tangible expressions of beliefs and their ways of working the land and water for gold. Their skin, their eyes, their hair prevented their acceptance as Australians. The Chinese lived and worked in tight socially cohesive groups of between 30 and 100 men, tied by kinship and locality of origin. Their ways of being and inhabiting social spaces did not align with that of the Euro-Americans on the goldfields.

In November of that year in Lambing Flat, a group of disgruntled white miners marched behind a German brass band, chasing off 500 Chinese from the field destroying their tents. By the following January the population of miners had swollen to 9,000. Historians have noted how Europeans tended to rush from one site to another as wild rumours of fabulous wealth lured them from payable claims. Historians suggests that the well-equipped and meticulous Chinese would move in and work the abandoned diggings, yet, were condemned for this practice. This is what occurred at Chinaman’s Dam, our picnic spot.

In the 1860s, two German brothers, the Tiedemanns, sold their land and dam to a group of Chinese who continued working the site for gold. However, here the sale of land to the Chinese was never officially documented and records only show that the area was Crown Land, despite the site having long associations with Chinese market gardening.

Back at Lambing Flat, tensions rose and fell until the following June 1861, when the large banner was paraded, drumming up supporters. Terrified, over 1,200 Chinese took refuge 20 kilometres away on Robert James’s Currawong property. Not all reached safety.2.See Karen Schamberger (2015) “An Inconvenient Myth The Lambing Flat Riots and the Birth of White Australia’ “Foundational Histories,” Australian Historical Association Conference University of Sydney.

It was reported on 10 July 1861 in the Melbourne newspaper The Argus that “… one man … returned with eight pigtails attached to a flag, glorifying in the work that had been done”. One can only imagine the horror for some in viewing this trophy and the sense of demasculinization it must have caused for the Chinese. Two years after the riots, the process of an “amnesia” towards the Chinese began intentional forgetting: indeed, the town of Lambing Flat changed its name to Young.

In the 1860s there were 38,000 “full” Chinese immigrants. By 1901, there were just under 30,000, and in 1947 the number dropped to 9,000. The Chinese disappeared from official Australian history once the full impact of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 came into effect. This was long-lasting.

The voice of the Chinese from the gold rush era in Australia is almost non-existent. There is no extant record of how the Chinese from the Lambing Flat goldfields felt about the violence inflicted on them.

The Chinese are central to the story of the Lambing Flat Riots yet, their narrative and their representation are poor, to say the least at the LFFM. Hints of the Chinese presence can be found within many small country towns by the fading and long-established Chinese restaurants. In Young, very faded signwriting indicated a Chinese restaurant, now a fast food outlet.

Unlike previous excursions, the domestic students were quite agitated in a discussion about the museum displays. Although some students did not appear to me to study the riot material, they nonetheless verbalised their embarrassment of the racist banner in the presence of Chinese students. We had a robust discussion on the role of museums and social inclusion, yet, noting the lack of control over who we visit with and its effect (and affect in this case).

It was apparent how quiet the Chinese students were. Trying to draw them into the discussion was a little difficult. I put it down to the fast pace of conversation and getting up to speed with English.

Eventually, it was revealed that they knew very little about the presence of and Chinese migration in nineteenth-century Australia. Despite the lack of objects in the museums and the horrors that they had read about on the walls, what they appreciated more were the Gardens, the design and the very peaceful atmosphere. “Very peaceful for the ancestors”, one student murmured. The Chinese students spent a long time inspecting the gardens, while other students talked in small groups about the weekend ahead.

The excursion ended up being a touchstone throughout the semester for all students. This museum was used as a prod towards thinking critically about museums. The issues raised were very direct. While some have argued that the Roll Up Banner should be in the National Museum of Australia or the Museum of Democracy, here in its original context it could be incredibly powerful with the Gardens as an adjunct to the visit, and the voice of Chinese people.

Admittedly I had been very dubious about the Gardens being so far out of town, relegating the Chinese again to the margins of local history. This time I had taken in the aesthetics of the landscape as a resting place and valued the response by the Chinese students.

Author

Sharon Peoples is a former lecturer in museum studies and has returned to her roots working as an embroiderer. She lives in Canberra and preparing for a solo exhibition ‘Still Waters’ at the Tuggeranong Arts Centre where she was artist in residence earlier in 2019.

Sharon Peoples is a former lecturer in museum studies and has returned to her roots working as an embroiderer. She lives in Canberra and preparing for a solo exhibition ‘Still Waters’ at the Tuggeranong Arts Centre where she was artist in residence earlier in 2019.

Related stories

References

| ↑1 | Anne Curthoys (2001) ‘Men of All Nations, Except Chinamen’ in Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook and Andrew Reeves, eds., Europeans and the Chinese on the Goldfields of New South Wales Gold; Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001) :103 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Karen Schamberger (2015) “An Inconvenient Myth The Lambing Flat Riots and the Birth of White Australia’ “Foundational Histories,” Australian Historical Association Conference University of Sydney. |