The Santiago design workshop Great Things to People recover deep geology to make objects for life today.

Volcanoes, scars, caves, ferruginous snows, skinned titanic heights…

Pablo Neruda Ode to the Andean Cordillera

✿

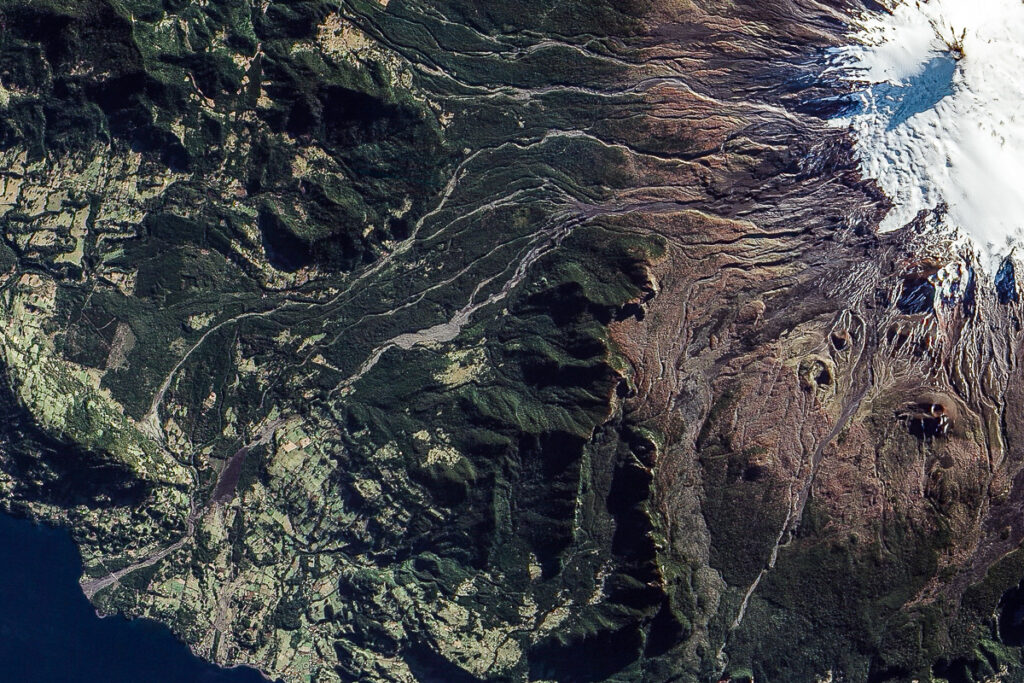

Chile is alive. Its territory stretches 4,000k north to south, from desert to glacier. Between mountain and ocean, it is never more than 200k wide. The geology was formed 200 million years ago, with the collision of the Nazca and South American tectonic plates, which caused the land to thrust up, creating the Cordillera, or Andes. Earthquakes still ripple through the land and volcanoes regularly erupt. There are 2,000 volcanoes in Chile, 80 of which are still active.

The Mapuche had many beliefs about the volcanoes, including their inhabitant, Pillan. But the Christian beliefs brought by Spanish settlers largely ignored the world they conquered. How would modern Chilean culture re-engage with this powerful force in its land?

Great Things to People is a design studio in Santiago that specialises in making Chilean stories out of objects. gt2P was founded in 2009 by Guillermo Parada, Tamara Pérez, and Sebestián Rozas. While producing high-end design objects for public spaces and museums, their program Made by Chile celebrates the local skills found in the country’s many artisan communities.

Their approach is a unique combination of analogue and digital. The studio integrates craft and design in a methodology called “para-crafting”. This method involves the manipulation of variables as you might find in algorithmic codes. But rather than computer code, it is expressed through material dimensions, such as temperature and shape. The aim is to create an object which emerges from the process, rather than controlled as in CAD or hand-carving.

Their work with volcanoes was inspired by a client who issued them with a challenge to make something using the volcanic stone in their garden. With their characteristic patience, over three years they gathered lava from across Chile to their studio and waited for an idea to emerge.

Guillermo Parada’s attraction to lava reflects the Chilean fascination for beauty in the lowly: “Lava is the garbage of the material world. Nobody studies it. Our knowledge is only related to disaster management.” One of their team, Victor Imperiali, was born in Puerto Varas, near the Orsono volcano and had spent his childhood wondering about lava.

In 2016, Tamara Pérez and Antonella went on a road trip to Orsono, Calbuco, Chaitén and Villarrica volcanoes. They drove for 15 hours from sweltering Santiago to the snow-capped south. Luckily, it was a rare sunny day when they collected the lava rocks from Orsono with hands and spade. Tamara recalls on the way back passing through Laguna el Maule with its remarkable obsidian deposits.

- Villacrica

In their second expedition in 2018, they visited Llaima which is Chile’s most active volcano. It was a much more disturbing experience. As Tamara recalls, “The sky and earth were both grey. I was terrified it would explode while we were there.”

Now there was a considerable heap of lava in the studio. What do to with it? The first process involved grounding the lava to a powder. To do this, they sought help from the geological facility of the Universidad de Chile.

The powder was then mixed with a molasses of sugar water, which burnt off in the kiln. In the kiln, the powder liquified and oozed over stools, planters, side and coffee tables. Temperature curves were varied in the kiln to allow for different material expressions of lava, including trapelco (smooth), mahuanco (dripped) and quitralco (rough). This was applied to The Remolten Monolita chairs reflected the transformation of the landscape by flowing lava.

Continuing their experimentation, Tamara discovered that the volcanic stone (Andesitas Basalticas) started to melt at 1260°C, which is around the same temperature for firing porcelain. In the studio, they were creating lamps by pouring porcelain slip into a cloth. Curves were manipulated by alternative folds in the muslin cloth with a series of weights. But there were problems: the anchor system was exposed and the hanging point was weak.

Here was the perfect solution. The lava melted slowly over the solid piece of porcelain, following gravity. It was cooled slowly so that it contracted gradually keeping the porcelain intact.

The resulting work was eventually exhibited as part of New Territories: Laboratories for Design, Craft and Art in Latin America at the Museum of Arts and Design of New York, which took place in November 2014. It was then acquired by the MET. The project as a whole is supported by Friedman Benda in New York.

Given the turbulence in recent times with the political protests in the streets of Santiago, Guillermo finds lava as a perfect symbol for his country. “Like a volcano, we put up with the government quietly for a long time, and then we suddenly explode.”

Despite its relevance, the work has never been exhibited in Chile. This is a common experience in the South. Argentineans looked down on tango until it started appearing in Paris clubs. Let’s hope that the northern exposure will help these works erupt into Chilean spaces.

See gt2p.com for more information.