Patrick Webb explores the mythologies of craft in classical Egyptian and Greek civilisations.

“Take advice from the ignorant as well as from the wise, since there is no single person who embodies perfection nor any craftsman who has reached the limits of excellence.”

Ptahhotep, 25th century BC

Relief of Ptah, Tomb of Nefertari (Illustration) – World History Encyclopedia, Manna Nader Gabana Studios Cairo

In the culture of every great civilisation there is certain to be found a cosmology, that is to say, a story or an account of the physical creation. For ancient Egypt, this cosmology surrounds the god Ptah. The name “Egypt” derives from “was hwt ka Ptah (the temple of the Ka of Ptah).” This alludes to the primacy within the Egyptian pantheon of, “Ptah, who gave life to all the gods and their kas (souls) through his heart and through his tongue.” Essentially, Ptah spoke the world into existence from out of his heart which for the ancient Egyptians was considered the centre of intellect and reason. This clearly is analogous to the ancient Greek and early Christian concepts of the Logos or Word that was instrumental in material creation.

So what kind of god was he? Well, the name “Ptah” is thought to mean “to sculpt” and in one ancient invocation the supplicant begins by hailing him as “great Ptaḥ, creator of crafts, sculptor of earth.” Furthermore, Ptah is described in the Book of the Dead as “a master architect, and framer of everything in the universe.” So although Ptah was considered a supreme deity, he was likewise regarded in ancient Egypt as having quite particular attributes as a god of the arts, crafts, and architecture. His very first creation was the god Atum, associated with the sun, illumination, and out of which everything else came into being. Atum was “self-engendered” that is to say he came out of Ptah, being a mode or manifestation of him. The Ka of Atum/Ptah is metaphorically described as semen, seeds that permeate and animate all of creation. Once again, analogies with the “logos spermatikos” of the Stoics and early Christians are readily apparent. Atum fashioned everything out of chaos represented as primeval waters or alternatively as the world serpent both being just further manifestations of Atum, making him at once creator and creation.

The City of Makers

There naturally arose a huge cult surrounding Ptah in Lower Egypt, centred at Memphis where numerous temples were erected and dedicated to his worship. Imhotep was a commoner that entered temple service as a priest of Ptah who displayed exceptional ability and rose to prominence as vizier and chief architect of the Pharaoh Djoser. Under his reign the first great pyramid was erected at nearby Saqqara, just outside the city; the step pyramid was part of a larger mortuary complex. Constructed in the 27th century B.C., it is the oldest such stone masonry complex known to exist. The pharaohs claimed their authority as descendants of Atum. Upon death their hope was to have the divine seed, the Ka within them reunite with Atum/Ptah. Eventually, Imhotep rose to the position of high priest of Ptah. As such he was bestowed the title “wer-kherep- hemutiu” translated as, “the great director of the craftsmen” thus earthly representative of Ptah. After his death Imhotep was deified as a demi-god, a literal son of Ptah.

Interestingly, another cult centre surrounding Ptah arose hundreds of years later near Luxor in Upper Egypt during the sixteenth century B.C. Deir el Medina was a small city of craftsmen that had been founded for the construction of royal and aristocratic tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings. The ancient name of the city was Set Maat meaning “place of truth.” The craftsmen living there were highly skilled freemen who were largely literate. Much of what we know concerning the daily life of common Egyptian people living at that time comes from archaeological discoveries of written accounts by craftsmen discovered at Deir el Medina. During this period another priest-architect arose to great prominence, Amenhotep, son of Hapu. Like Imhotep, he too was deified as a demi-god son of Ptah after his death. So revered was Amenhotep by the craftsmen of Deir el Medina that he had chapels constructed and dedicated to him at the local Temple of Hathor as well as the nearby Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari.

“Chaos was first of all, but next appeared broad-bosomed Earth, sure standing-place for all the Gods who live on snowy Olympus peak, and misty Tartarus, in a recess of broad-pathed earth and Love, most beautiful of all the deathless gods.”

Hesiod, Theogony

Quite different from the Christian conception of a God who creates the physical universe ex-nihilo (out of nothing) or the strikingly similar (some might say compatible) scientific theory of a Big Bang, the ancient Greek view held that matter is eternal, that it always existed. The primal state of matter was personified as Chaos, literally a chasm or abyss to indicate something infinite, shadowy, alive, and perhaps even conscious. A number of primal entities, powerful yet primitive deities were said to emerge from her into independent being. There was an initial bringing into an orderly arrangement of the unformed matter originating in Chaos by these primal entities. Notable among these figures are the Moirai or Fates, depicted as weavers who through their craft set limits thereby imposing a natural law and order that formalises a “cosmos” to which even the Titan and Olympian gods were subject.

The Demiurge

Constantin Hansen, Prometheus Creating Man in Clay, Sketch for the left half of the fresco in Copenhagen University’s vestibule, circa 1845; WikiCommons

It is into this existing cosmos that the Olympian gods make their debut. Chief among them is Zeus (Jupiter), also known as “Zeu pater” exalting his role as both father and pattern maker. Zeus was not a creator of things ex-nihilo, instead he was depicted as an artificer of existing material that continued the project of increasing physical order in the cosmos as well as in human activity through law and justice. Plato in the Timaeus describes this activity as the work of the “demiurge”, literally meaning a working man or craftsman. The later neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus directly identifies this demiurge fashioner of the world with Zeus. At times Zeus’ interventions were direct; however, more commonly he would command other gods and titans to do his bidding. A preeminent example of this is the creation or fashioning of men and women.

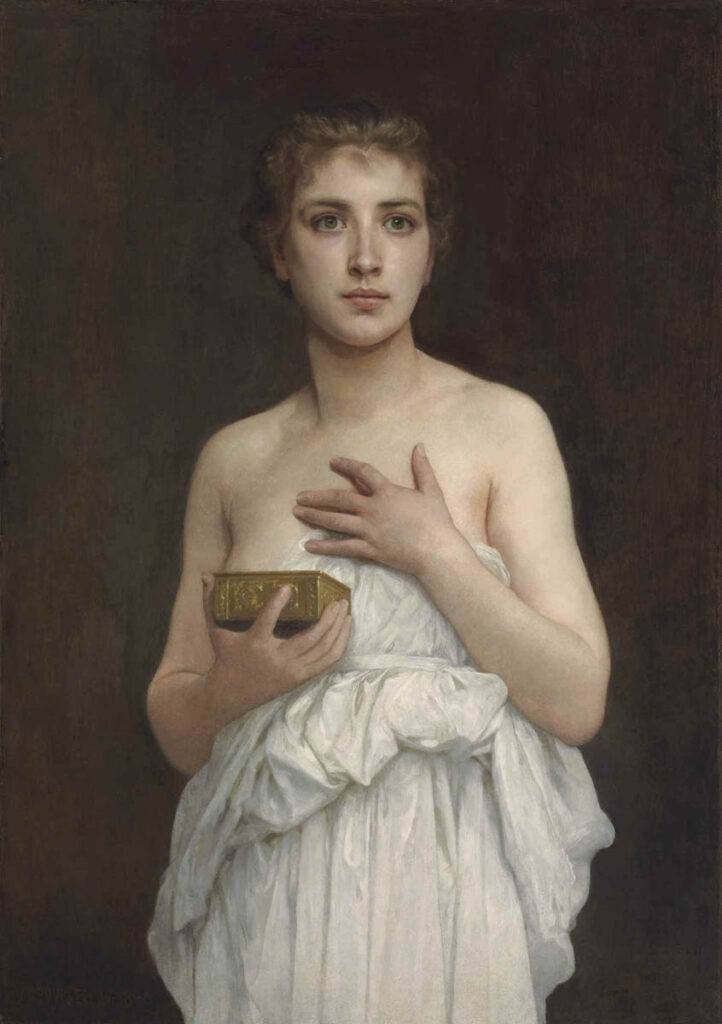

Zeus had commanded the titan brothers Prometheus and Epimethus to fashion mortal creatures to fill the earth. Epimethus took the lead with the animals whereas Prometheus held a particular interest in man whom he sculpted in his own image out of a mixture of elements of the very earth, smoothing the contours with his own tears. His handiwork complete, Prometheus called upon Athena to animate the clay so that it became a living man. Prometheus was very proud of and jealous for mankind, famously stealing the divine fire from Zeus on their behalf. Furthermore, he raided the workshops of Hephaistos and Athena to supply man with all the tools for craftsmanship. Displeased with Prometheus’ actions, Zeus subsequently commanded Hephaistos to fashion a woman which he sculpted from the earth following Promethus’ example. Once again, Athena breathed life into her; the Olympians in turn all provided her with a parting gift, hence her name “Pandora” meaning many gifts. Thus both man and woman are presented in Greek myth as artefacts, crafted objects made by and separate from the divine.

Gods of Craft

“As when a man adds gold to a silver vessel, a craftsman taught by Hephaistos and Athena to master his art through all its range, so that everything that he makes is beautiful.”

Homer, The Odyssey

All of the Olympians at one time or another are shown to be capable craftsmen and artists, reflective of the value placed on craft and the respect accorded the craftsman in ancient Greece. Nevertheless, Hephaistos and Athena are particularly renowned for both their skill as well as their generosity with mankind. Hephaistos was considered primarily a metalsmith of bronze; his eternal forge was located within Mount Etna. Additionally, the arts of carpentry and stonework are likewise credited to him. Hephaistos was a lover of philosophy and the arts that helped to civilise mankind by bringing him forth from the cave, equipping him for a societal life in houses of his own construction.

Athena was likewise known by the title “Ergane”, meaning “worker” thereby highlighting her role as mistress and patron of architecture, the arts and crafts. She was particularly skilled in weaving, an echo of the Moirai who weave the very cosmos. Likewise she held great expertise in carpentry, instructing a number of men in shipbuilding and famously in the building of the wooden horse that led to Greek victory in the Trojan war. Athena was quite generous with her skills and had the reputation of being the most personal of the gods with mankind, always seeking their enculturation and betterment. Though a virgin goddess, she was the one to endow life to the first man and woman and thus has been rightly construed as a mother figure who perhaps elides the sharp distinction between god and man. Naturally, she was the patron goddess of ancient Athens and the Parthenon dedicated to her was the centrepiece and crowning jewel of the acropolis temple complex.

The Heroic Craftsman

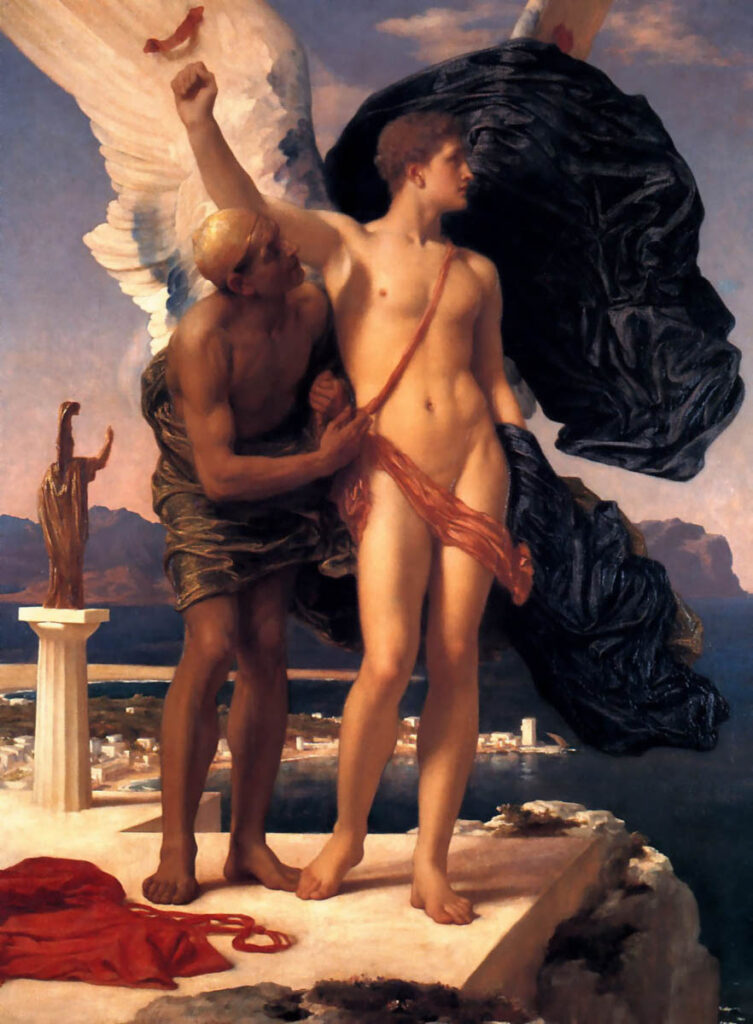

The Parthenon is widely acknowledged as among the most finely crafted buildings in human history as contemporary restoration attempts are bearing out. It was constructed under the direction of Iktinos and Callicrates, two architects each of whom quite literally was an arch (master) tektōn (craftsman) that is to say, master masons. They were assisted by significant contributions of the great sculptor Phidias placed in charge of the carved decorations. The Athenian philosopher Socrates would have witnessed the erection of the Parthenon from start to finish in his lifetime. Socrates’ father was a stone carver and he proudly claimed descent from the hero craftsman Daidalos so ultimately Hephaestus himself! Daidalos was by far the greatest craftsman of mythical antiquity credited with initiating the tradition of humanistic lifelike statuary. He was commissioned by King Minos of Crete to design the labyrinth containing the Minotaur who subsequently locked him up within so its secrets could not be revealed. Undaunted, Daidalos proceeded to fashion wings for he and his son Ikaros by which they make their escape, tragically so for Ikaros. Burying his grief, Daidalos continued on to Sicily where he constructed a temple to Apollo.

Unfortunately, this crowning zenith of admiration for the craftsman ensconced in religion, myth, and culture was not to endure in waning Classical Greek or for that matter Western civilisation. The craftsman possessing skills such as the tektōn or ergos were initially distinguished from the thetes (foreign day labourers) or dmoes (slaves and serfs). Yet, the distinction collapses a mere two generations later as Aristotle makes his case for why banausoi (a derogatory term for so-called vulgar artisans) should never be allowed citizenship: “Now we speak of several forms of slave; for the sorts of work are several. One sort is that done by menials: as the term indicates, these are persons who live by their hands; the vulgar artisan is among them…those who provide necessaries for an individual are slaves, and those who provide them for society are handicraftsmen.” Aristotle further expounds on why craftsmen should be considered the very lowest form of subhuman, even below slaves as he offers his justification: “For a slave shares his master’s life, whereas a vulgar craftsman is at a greater remove.”

About Patrick Webb

Raised squarely in the Arts & Crafts tradition, Patrick Webb was formally trained as an architectural stone carver and has worked primarily as a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of historically utilised plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime, and natural cement in contemporary architectural specification. Visit Real Finishes.

Raised squarely in the Arts & Crafts tradition, Patrick Webb was formally trained as an architectural stone carver and has worked primarily as a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of historically utilised plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime, and natural cement in contemporary architectural specification. Visit Real Finishes.