Ningyo-Joruri is a form of theatrical performance that is more than 500 years old. It is a combination of a puppet show and Joruri, a musical narrative in a style called Gidayu-bushi that focuses more on storytelling than singing – with the accompaniment of shamisen, a three-stringed musical instrument. Ningyo-Joruri was designated a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008 together with Bunraku, a similar kind of traditional puppet theatre, and Nohgaku and Kabuki, the two major forms of Japanese drama. It has become one of the most well-known Japanese traditional performing arts.

However, in reality, most Japanese people today are unfamiliar with Ningyo-Joruri. My parents, who are in their late 70s, grew up in the central part of Tottori Prefecture in western Japan from childhood until they finished high school, but they say they have never seen a Ningyo-Joruri performance. My grandparents on my father’s side taught Noh chants, and Kabuki was aired on radio at the time. Still, they did not even know that there were a few Ningyo-Joruri companies in Tottori City.

To be honest, I am not naturally acquainted with Ningyo-Joruri. I lived in Osaka for 20 years, home to Bunraku, but I have never had a desire to go and watch it. The vocalisation of Gidayu-bushi that continuously rises and falls between high and low pitches was unfamiliar to me. The stories based on the sense of ethics bound by loyalty and empathy often sounded unreasonable. It is also quite odd that stony-faced puppets play human dramas. I think it requires a certain amount of discipline to appreciate Ningyo-Joruri.

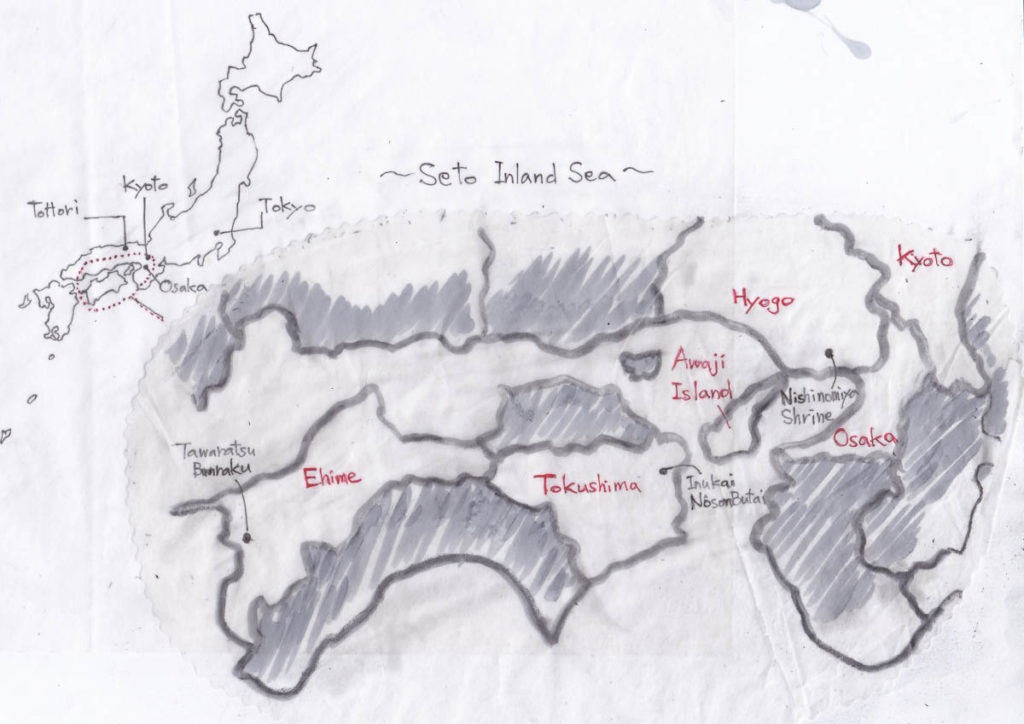

I have lived in Kyoto for more than 20 years, researching dyed fabric works and clothing ornaments. For the last six years, I have focused particularly on costumes in Ningyo-Joruri across the Seto Inland Sea in Awaji Island in Hyogo Prefecture, Tokushima Prefecture (formerly known as Awa) and Ehime Prefecture. The reason why I picked up this theatrical art is not that I understand it fully, but because I feel the passion of the people who lived 70 to 100 years ago is woven into its costumes. Those costumes are from the time when troupes of Ningyo-Joruri travelled all over Japan, even occasionally to some of the former Japanese settlements abroad, and became successful as mass entertainment.

Today few people know about that time. My knowledge of Ningyo-Joruri comes from books written by those who feared that it was on the verge of extinction, and stories told by some elderly people to the current members of remaining troupes.

It all began with Shinto rituals in the Seto Inland Sea. Ningyo-Joruri has its roots in puppet performance as a tribute to Ebisu, the god of fishery and business. It was brought to Awaji Island, the largest island in the Seto Inland Sea from Nishinomiya Shrine in Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture in the mid-sixteenth century. The techniques became refined among the islanders. During the Edo period (1603-1867), Ningyo-Joruri received patronage from the feudal lord of Tokushima (Awa) domain who ruled the island. The troupes were able to tour around the nation.

The repertoire emerged from a kind of dancing in Shinto rituals. At that time it included Gidayu-bushi, a form of storytelling and singing that was popular in Kamigata (Kyoto and Osaka area), and featured tales of historically important warlords or the trials and pathos of townspeople. Over time a technique of manipulating the puppet with three puppeteers instead of just one was developed, and gradually this turned into today’s Ningyo-Joruri.

Awaji Island was incorporated into Hyogo Prefecture, in northern Honshu, during the Meiji period (1868-1912), but some of the troupes moved to Tokushima Prefecture. Blessed with the natural resources of the Seto Inland Sea and the Yoshino River, there were rich merchants and village leaders who made fortunes through the production of indigo and salt. There were also stages that they used to invite Ningyo-Joruri performers to reward their employees and villagers.

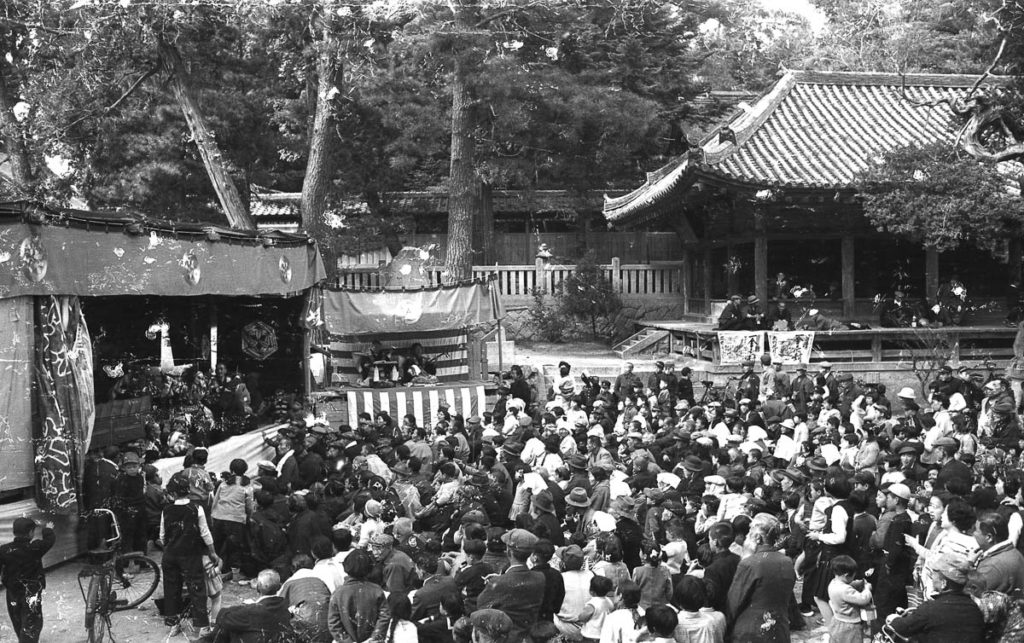

The stages were called nogake (also known as koyagake or kakegoya), which were mobile outdoor stages set up on unused fields, the premises of shrines and public spaces, or in large gardens of prosperous merchants. Performances were held from morning until night, when oil lamps were lit after sunset. It is said that audiences brought lunch boxes and sake, called out to the performers and chimed in with the lines and songs. They enjoyed the shows to their heart’s content, being freed from their daily hard work.

On the other hand, Ningyo-Joruri performances in other cities declined as new types of theatrical play and entertainment started to gain popularity. Among these, the arrival of cinema during the Taisho period (1912-1926) was particularly damaging. To make matters worse, the Pacific War (1941-1945) deprived people of any form of entertainment and performers of their jobs. Even though many troupes managed to come back after the war, professional ones ceased to exist during the period of rapid economic growth between 1954 and 1973 as the waves of changes in people’s lives and cultures reached every corner of rural areas in Japan.

By contrast, the local troupes in the villages of Tokushima and Ehime prefectures had patiently continued their activities to preserve the long-lived artistry and the enjoyment of local people. As a result, Ningyo-Joruri has been designated as an intangible cultural property by the national and prefectural governments since around 1960s (in 1959 Ehime, in 1976 Awaji, in 1999 Tokushima), and is still alive as a local traditional performing art.

Costumes of the past

Ningyo-Joruri’s costumes of early times are made so they stand out even on a dimly-lit stage. For example, a kimono with an appliqué motif cut from muslin material dyed with synthetic dyes of colours like bright red or purple.

A dragon embroidered with golden-coloured threads is a symbol of a warlord or brute. Every troupe had one of these intricately crafted costumes and used it in highlights of stories. Golden-coloured threads were lavishly used to create a reflective effect; cotton was stuffed into embroidered embellishments to make them swell. The dragon’s eyes were glass balls that glared at the audience in every direction.

The costumes with embroidery works that were especially worth viewing were hung on bamboo poles and displayed in front of the stage. This stage decoration was called Isho-yama (mountain of costume).

At the same time, the Japanese people’s way of taking good care of things and not wasting them can be observed in how the costumes were handled. Some costumes were made from secondhand kimono materials or scraps from old costumes stitched together. Old curtains and banners were used as a liner. These works still carry the warmth of the makers’ hands.

Such old costumes are kept in local museums or the storage of troupes that are still active. However, most of them are in poor condition. Costumes are consumables to begin with. Contemporary dyes can easily become faded or stained, and fabrics can get eaten by worms during long-term storage. Some of them are in really bad shape.

Keiko, a costume maker of today’s Ningyo-Joruri

In Tokushima, there are fifteen or sixteen Ningyo-Joruri organizations (registered with the Promotion Association). It is said that many women are involved, often starting Ningyo-Joruri after their children have grown up and they have less housework to do. In some troupes, women make up 80% of the members. It is encouraging that they are supporting the regional performing art, however their expertise in stage set-up or costumes can often be minimal because the purpose of the troupes is not to make profits or attract more spectators.

Lighter materials and ornaments are used for today’s costumes to make it easier for puppeteers to manipulate the puppets. Some of those that are especially luxurious are ordered and made in Kyoto, where I live, using techniques of Nishijin-ori (a kind of brocade made in Kyoto) and embroidery. Nowadays, golden threads are made of aluminium that doesn’t rust easily and can be used on embroidery sewing machines. Thick and heavy embroidered works have become products of the past. Today’s dyed costumes tend to have colours that look flat and designs that are very derivative.

Yet, I met a woman who has pride in her way of making costumes in Tokushima. Keiko Yabe had originally been a hobby painter of Japanese-style paintings. When she was planning to draw a picture of Ningyo-Joruri, she was asked to join the performance. There were openings for puppeteers of Ningyo-Joruri to participate in the National Cultural Festival that Tokushima hosted in 2007. She made a costume for her puppet for the first time by following the examples of others. Later, she went to a school that taught how to carve the heads of the puppets, where she met Yoneko Bando who was in her 80s then. She was the first female puppet maker in Tokushima and was teaching at the school. She started to teach Keiko how to make costumes. Keiko has a good sense for costume making because she knows the structure of a puppet’s head and she can manipulate the puppet. Keiko makes everything from hair accessories to tabi (Japanese socks with parted toes). She has been improving her skills and creativity while receiving orders from Kanroku (formerly known as Kanroku Yoshida), who moved from the Bungaku-za Theater in Osaka to Tokushima to teach a troupe there.

Keiko says that soft textures and deep colours are suitable for Japanese traditional hairstyles and dressing especially because the tales of Ningyo-Joruri are set in historical times. Therefore, she chooses old kimono materials made of silk or cotton and sews the costumes by hand. She uses old kimonos that she used to wear, and buys antique kimonos and materials online, washes and prepare them, and makes them into costumes making sure that they are durable.

In one instance, Keiko received a piece of material that was stained badly. She guessed that it was part of a banner from 100 years ago that was put up to celebrate the birth of a child. When she washed the dirt away, the deep colour of indigo came back to life. It was patched together with other pieces of fabric to be made into a costume, which elegantly shone under the stage lighting. Indigo, one of Tokushima’s local products, used to be the colour that Japanese common people wore. Among more than 40 costumes she made in the last eleven years, with few remaining at her place, she says that this costume is her most memorable work. I was deeply impressed by her passion for the colour of indigo.

A device called nogake

I think that the slight strangeness I feel about Ningyo-Joruri may disappear if I could see costumes crafted by makers like Keiko who are particular about the nuances of colours and materials on an outdoor stage—the nogake.

Ehime Prefecture is where Ningyo-Joruri troupes of Awaji Island and Tokushima toured often. As such, the seeds of this art form were sown a long time ago in Ehime Prefecture, which also grew through exchanges with Bunraku in Osaka. The southern part of Ehime has as many as five troupes that have been supported by the local people until today. Tawarazu Bunraku in Seiyo City, Ehime Prefecture, has more than 100 years of history. They built their own theatre on the quiet coast, where about 30 members give performances in spring and autumn every year.

Kazuo Shinokawa with his member and a female shamisen player from Tokyo, Sansuzu Tsuruzawa in the theatre

The leader of the troupe is Kazuo Shinokawa, 90 years old, who is a Gidayu narrator. He has been teaching the members in a strict manner to improve their skills. When I visited him, he shared some interesting episodes from the time when he was younger. He said that it was fun to discuss who had the luck of staying at the house offering the best hospitality when the troupe toured and stayed overnight at different residences of the local people. He was also amused that the audience was always cheerful and enjoyed their show even when the members had been drinking the night before and performed poorly. According to him, the building materials of the nogake stage that they carried and used at the time should still remain somewhere in the warehouse. He is the only person left who knows how to construct a nogake.

The members of his troupe were teaching sixth graders to prepare for their school performance while I was there. I imagine that the children would be proud if they learned the history of this troupe that has travelled across Japan.

Inukai Noson Butai or Inukai farming village stage provided by Tokushima Prefecture Awajurobeyashiki

There are still about ten permanently installed outdoor theatres that have old-style small structures in Tokushima Prefecture. Props and tools are brought into these places to set up puppet shows. One such theatre is named Inukai Noson Butai (Inukai farming village stage) whose grand device to change the stage setting is a reminder of how powerful the culture of Ningyo-Joruri used to be in the past.

These theatres are located far from the centre of Tokushima Prefecture, but people from in and out of the prefecture visit them to see the events conducted under the operation of the preservation association. During the cherry blossom and autumn leaves seasons, crowds cheer at the shows while seated on the ground.

Still, the real power of performing arts lies in the festive enjoyment it can bring for both performers and viewers – taking place in a small structure, suddenly set up in the everyday scenery, with banners and grand drapery. The inside is lit up, the music plays loudly, puppets move around as if they are alive, and people are laughing.

I sincerely hope that nogake start to travel again and are restored in various places across Japan, as they provide opportunities for people outside the Tokushima Prefecture to experience the kind of excitement that audiences must have shared a long time ago.

This article was translated from Japanese by Maiko Muraoka

Special thanks and resources

Keiko Yabe

Garland Magazine

Eloise Rapp

Tawaratsu Bunraku

Kenji Sato and Sachi Komada, Tokushima Prefecture Awajurobeyashiki

Katsutoshi Nakamura, Minamiawaji City Awaji Ningyo-Joruri shiryokan

Kitajima Town Library and Sosei-Hall

Minamiawaji City Office

Masaaki Nomizu

Yasuhei Miki

Hideo Nakanishi

Soshichi Kume “Awa No Ningyo-Shi”, “Awa To Awaji No Ningyo-Shibai”

Mune Torataka “Awaji Nogake Joruri Shibai”

Author

I have lived in Kyoto city over for twenty years. I studied Japanese textile history in Kyoto University graduate school, which is associated with the Kyoto National Museum. I’ve worked on research with collections of temples, including exhibitions and conservation. I encountered the costumes of Ningyo-Joruri through an assignment for Tottori Prefecture. The current conservation activity is at a historic but small-scale Zen temple in Kyoto city. I hope to use my skill for private collectors and temples outside Kyoto city who find it difficult to maintain their collections.

I have lived in Kyoto city over for twenty years. I studied Japanese textile history in Kyoto University graduate school, which is associated with the Kyoto National Museum. I’ve worked on research with collections of temples, including exhibitions and conservation. I encountered the costumes of Ningyo-Joruri through an assignment for Tottori Prefecture. The current conservation activity is at a historic but small-scale Zen temple in Kyoto city. I hope to use my skill for private collectors and temples outside Kyoto city who find it difficult to maintain their collections.

Comments

I thought bunraku and ningyou joruri is the same. So it is different? What and how is the difference?