- Sarah Tomasetti, Gauri Kund – The Lake of Compassion, fresco

- Sarah Tomasetti, Mist over Vajrapani, fresco

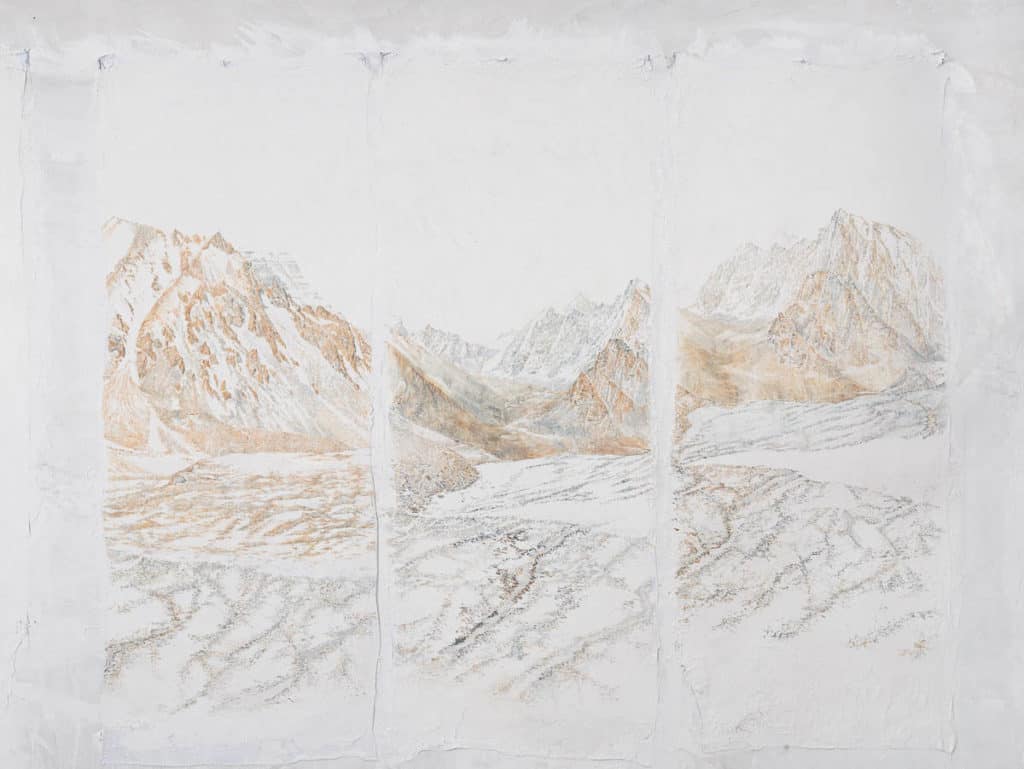

- Sarah Tomasetti, Sarah Tomasetti Dolma La, fresco

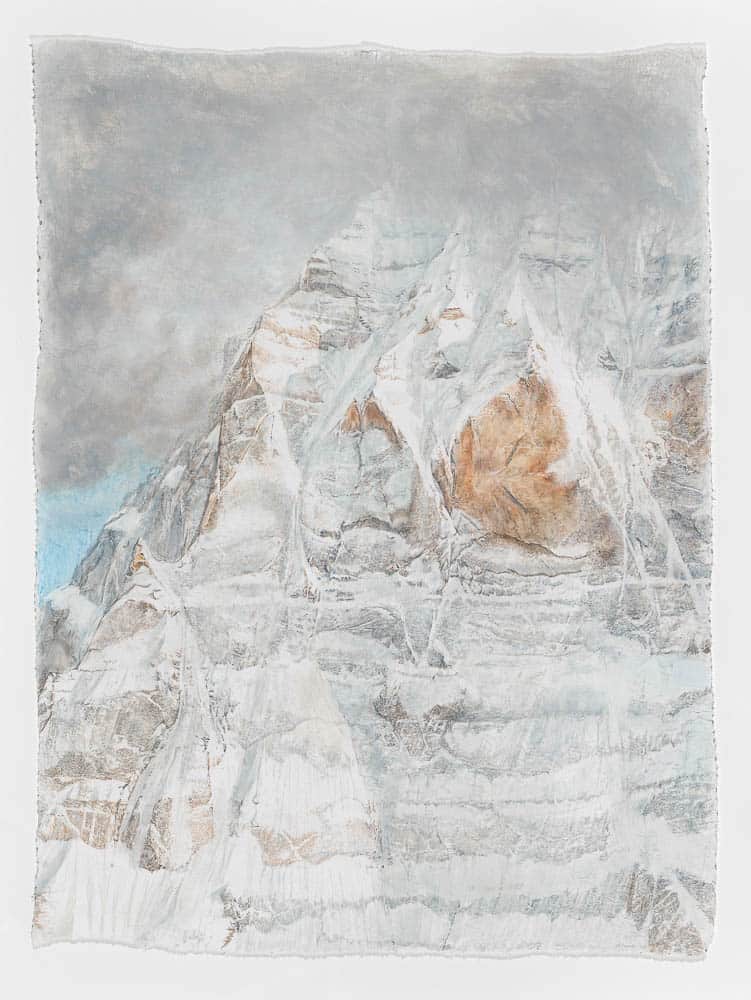

- Sarah Tomasetti, Kailash North Face IV, fresco

- Sarah Tomasetti, Silver mountain, fresco

- Sarah Tomasetti,

- Sarah Tomasetti, Kailash North Face

- Sarah Tomasetti

Sarah Tomasetti discovered fresco in Italy. At the age of 23, after finishing a BA in Fine Art, she went to study Italian in Perugia. Curious to follow the train line to Assisi, she walked into Giotto’s Basilica Papale di San Francesco. “There was something about the luminosity in that space. I had this sudden desire to learn how to do it”.

On returning to Melbourne, she completed a postgrad year at Philip Institute but also studied two years of Italian language. Returning to Italy, she found a fresco school in Prato created from the studios of restorer Leonetto Tintori. She stayed for seven months of in-depth study.

She learnt more than a simple technique. “Initially, coming from a mixed media approach, I walked into a setup where there were prescribed instructions for each stage. It was difficult and I felt homesick for the freedom of my studio. But when I came back, I imposed that restriction on my work, to see what will happen.”

Fresco is part of the architectural fabric, which makes it a magical art for conveying a special sense of place. It is not an image that moves around the world in travelling art exhibitions. But what about visiting artists? To cater for foreigners who wanted to take home samples of their work, a method evolved of placing washed hessian beneath the last layer of plaster. When this dried, you could lift it off and mount it on wood to make a portable sample.

Refining the technique back in Melbourne, Sarah used increasingly fine fabrics, eventually settling on muslin. The key substance was the lime putty, which is produced by an ancient alchemical process. She tries to minimise crude cracking by using increasingly fine aggregate, replacing sand with marble dust. When waxed, it brings out tiny intricate cracks that are internal to the skin of the fresco.

More traditional frescoes convey scenes from the Christian Bible. While Sarah brought back the traditional technique, she radically changed the subject matter. She traces the choice of mountain as a subject to several visits to New Zealand’s South Island, where she was impressed by the glacially formed landscape.

This led her to consider the sacred mountains of the world, eventually leading to Kailash on the western side of the Tibetan plateau. This mountain is treated as a living deity by Hindus. Rather than scaling it to the summit, pilgrims circumambulate it in an exacting ritual known as the kora, performed over weeks on the hands and knees. Though tempting to climbers, the respected mountaineer Reinhold Messner refused the offer to the summit: “If you scale this peak, you take something away from people’s souls.”

Sarah is interested in the way the snow-capped peak can represent something distant and longed for and how nostalgia forms in absentia. She is currently collecting stories about landscapes that people who have migrated to Australia have left behind to add to an archive of images entitled the Remembered Landscapes Project.

Though done with painstaking detail, Sarah’s method avoids photo-realism. She builds up the detail on the soft surface with fine hand processes like stippling and engraving. She constructs the rock face, scratch by scratch. “I’ve tried to take out the inflection of gesture usually associated with painting. It is an intense process of subtraction. There is no sky or base to the mountain. It is monumental but ephemeral.”

Sarah’s works parallel the kora as a kind of devotional response to the mountain. Her representation does not capture the image, but reflects the deep time processes that brought it into being.

In craft and ambition, it evokes the Tree Ring by Marian Hosking, which sought to evoke the monumentality of Australia’s largest tree, a mountain ash, by making a wax impression of its circumference. The tiny details of its bark were then revealed when cast in silver as a gigantic ring.

So even if Sarah has transplanted a tradition of religious iconography in fresco to a modern secular culture on the other side of the world, she has retained its power as an expression of the sacred. Along the way, she has revealed the third-dimension within the painted surface. Her work is not just about capturing an image of the world, it is a material echo of the geo-physical processes that brought it into being.