- Wattle repeat asemic writing, spring 2018, direct exposure from material collected at the site, photo: Emma Byrne

- Penleigh Boyd, The breath of spring, 1919, oil on canvas, 122.0 × 154.0 cm, Warrandyte, Victoria

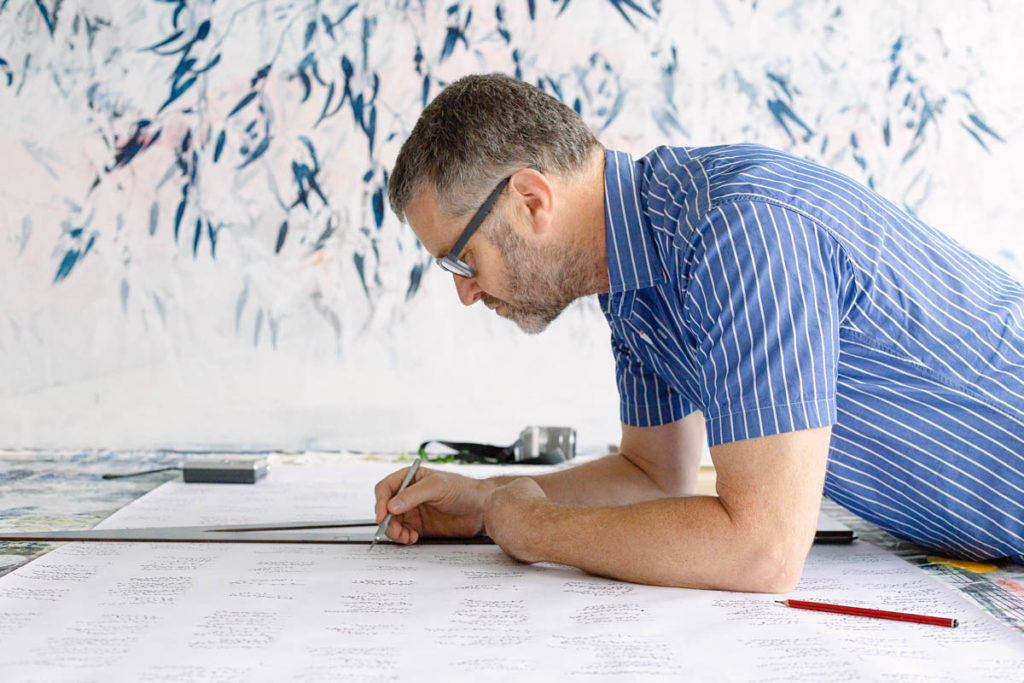

- Field trip, Warrandyte, 2018

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

- photo: Emma Byrne

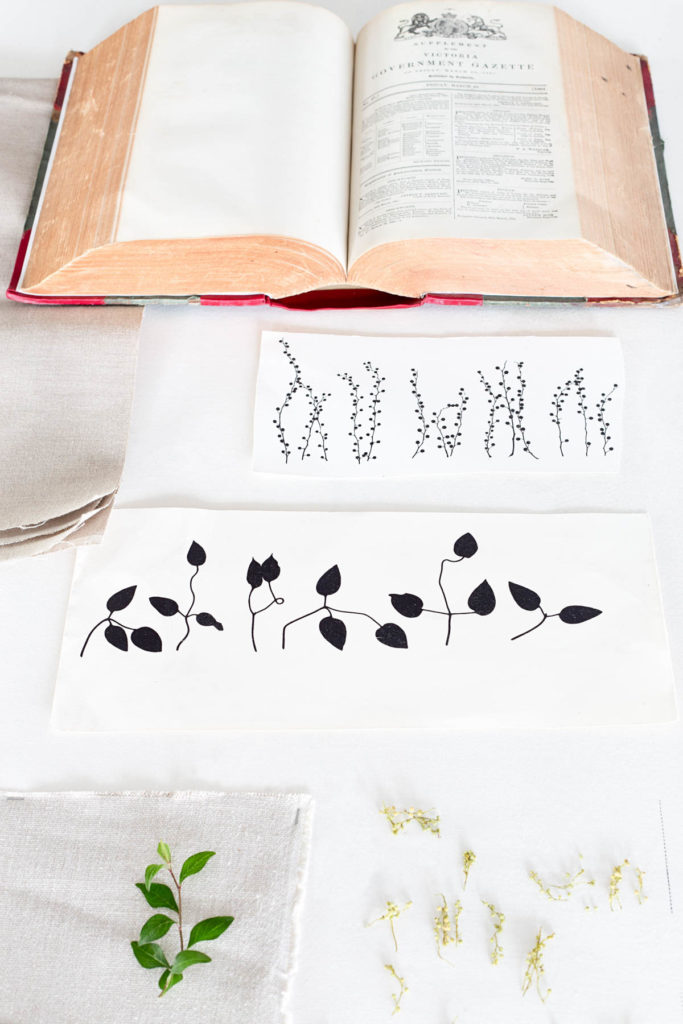

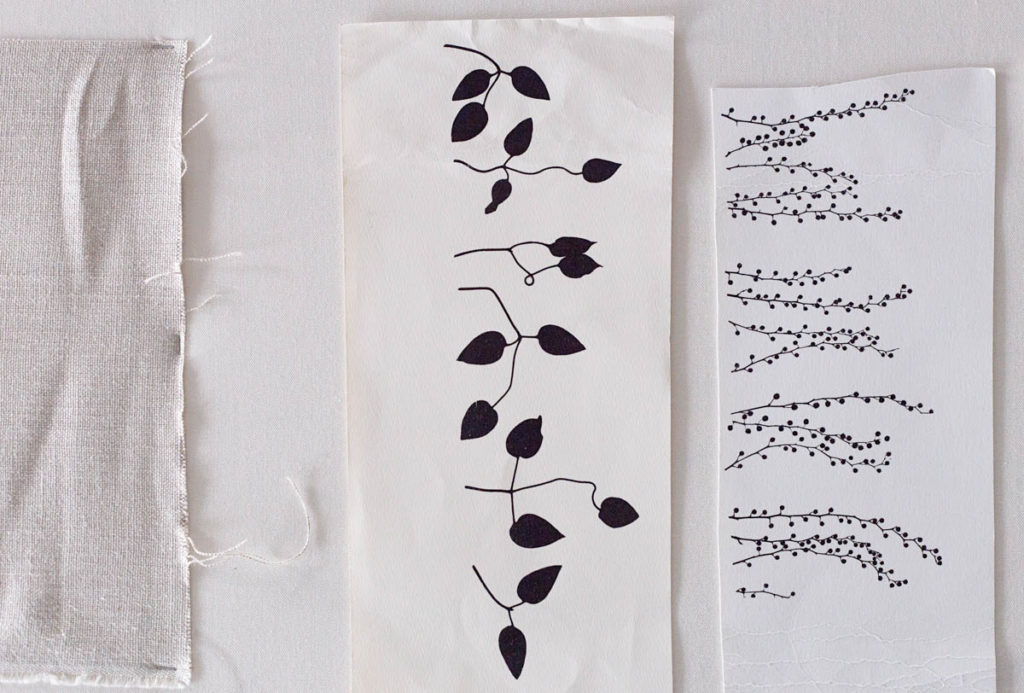

In Spacecraft’s series of commissioned prints for KFive + Kinnarps’ Boyd Collection furniture, site, history, language, art and architecture intermingle under the guise of soft-furnishings. On face value, these textile designs are simple botanical prints that take the specificity of trees as a motif. The silhouettes of leaves, vines and flowers are assembled, repeated and mirrored onto linen.

But deeper, beyond the “upholstery” of surface, these designs speak of a skilled, curious studio who bring craft, research and experimentation to their work across commercial, artistic and architectural projects. In one of their Boyd Collection textile designs, the silver wattle ( Acacia dealbata) is inverted and digitally edited to form a spindly asemic (or wordless) page layout, complete with open-ended “punctuation”, “footnotes” and “text”. For this commission, Spacecraft took inspiration from the writing and architecture of Australian architect Robin Boyd (KFive + Kinnarps’ posthumous collection is based on Boyd’s own furniture which he designed for his Walsh Street family home and the nearby Domain Park flats project in South Yarra), a prolific writer and public advocate across news media, books, television, radio and exhibitions. Boyd was a born communicator of modernist ideals and the value of integrating architecture with the everyday. So too this series of botanic symbols can be seen as ciphers through which to consider how we live with nature; can our cities be places of coexistence with, not the eradication of, our environment? What is present before we build and design? How can process and product come together to tell the story of an ongoing practice in which art, craft, design and science converge while giving a nod to a modernist architect-intellectual?

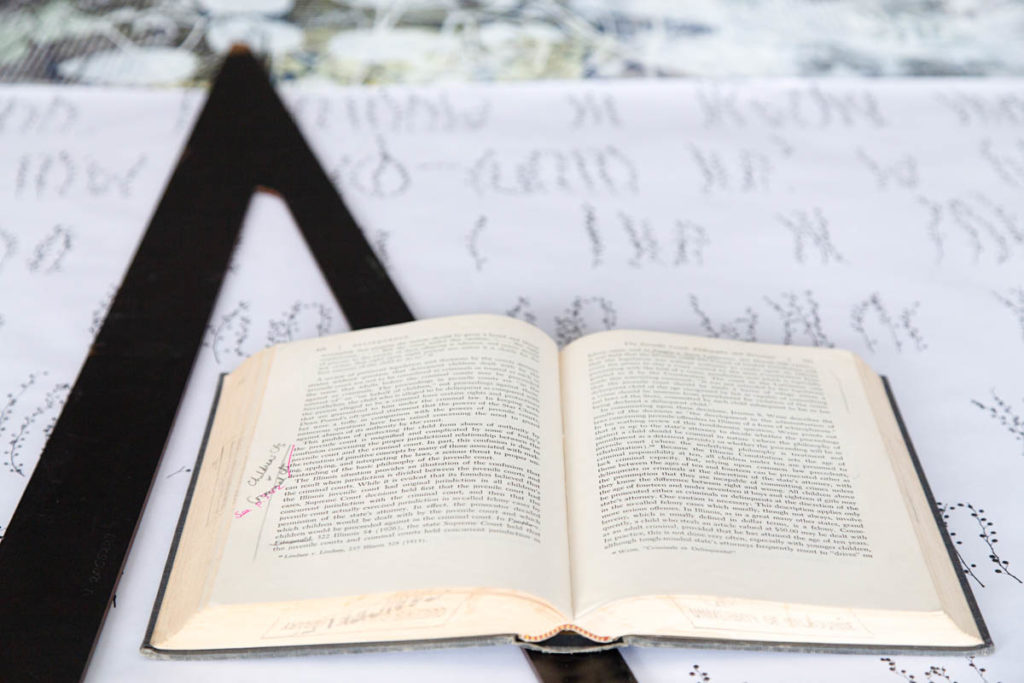

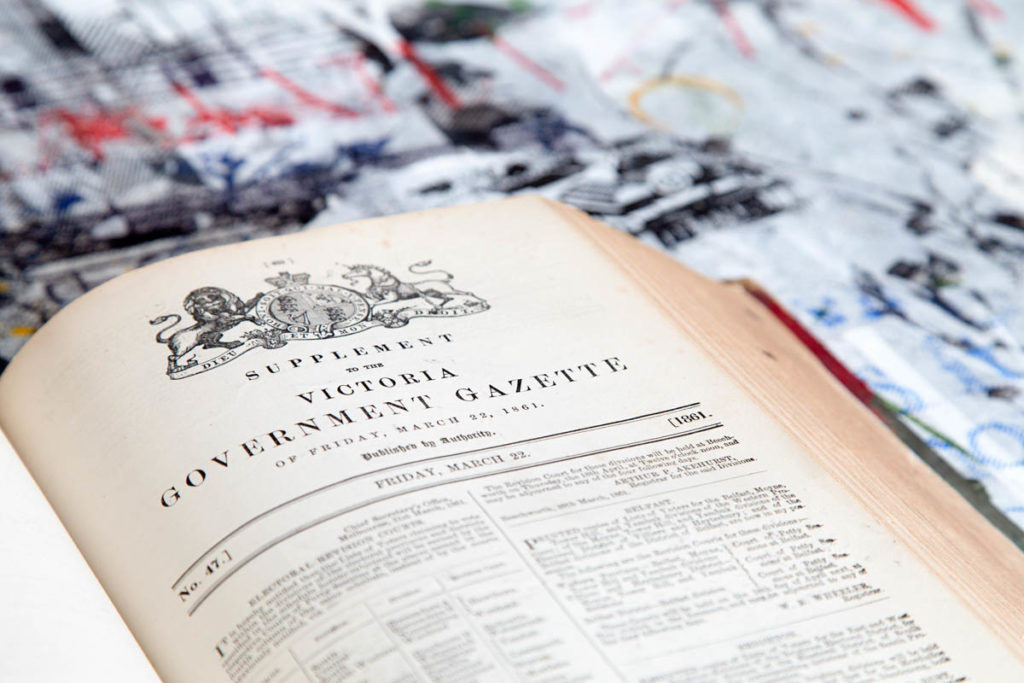

I’m in the Spacecraft studio in Collingwood on a baking-hot day in November, here to learn more about the process behind the series while the small studio team works in symbiosis. Stewart Russell (Spacecraft co-founder and artist) and Clara Gladstone (artist) tell me about The breath of Spring (1919), a dreamy Impressionist-style oil painting (in the NGV’s collection) of the silver wattle which Penleigh Boyd painted en plein air near the Robins in Warrandyte (north-east of Melbourne), a one-of-a-kind Edwardian-meets-Arts-and-Crafts home he designed and built—and the birthplace of his son Robin in 1919. Russell and Gladstone identified the silver wattle through several visits to the house and surrounding area and allowed the site’s history and plant life to imbue the studio’s iterative and generative approach to the commission. I’m shown silkscreens that have been exposed to a UV light source; plant forms imprinted as negative space in a sea of blue exposed photo emulsion. And as we talk, I see evidence of the studio’s seamless workflow between the handmade and the digital. On screen, Danica Miller (designer and studio manager) shows me the digital file for the aforementioned asemic wattle print, painstakingly layered and edited to suggest a botanical language. The original wattle fronds were “souvenired” by Gladstone and Russell from the banks of the Yarra, as close as they could estimate to the site of the original painting in Warrandyte. Here, they also made “direct exposures” of the heart-shaped leaves from an old gum tree in the garden, vacuum-sealed to create true contact with the photo emulsion. Usually, silkscreen exposure to UV light is a highly controlled process indoors in the studio, but here, sun, atmosphere and the history of the site become the source of form, light and shadow.

Spacecraft’s work is born from conversation, enthusiastic research into artistic, literary and design precedents, and the interplay between handcraft, materiality and digital production. The story behind this commission continues that ethos and collaborative spirit, and comes from a kind of three-way conversation between the Spacecraft team, Erna Walsh (CEO of KFive + Kinnarps, a Melbourne-based furniture design wholesaler and retailer founded in 2001) and the Robin Boyd Foundation (established in 2005 by architect Tony Lee) which continues Boyd’s design advocacy through onsite talks, workshops, screenings and exhibitions from Boyd’s own Walsh Street residence, a still-active time capsule, relatively unchanged since the 1960s. Boyd’s pared back furniture, made from Australian hardwoods and wool, have been reissued according to the same specifications as the original designs by KFive + Kinnarps, but with a new range of fabrics and palettes for a contemporary era. Each year, a new designer is invited to design textiles for the Boyd Collection, with the proceeds from each sale donated back to the work of the Foundation. Spacecraft’s designs will grace the three-legged “Walsh Street” sofa and “Domain Park” chair, to be printed on Belgian linen or wool.

The first design in the series pays homage to the silver veined creeper that grows across sandstone walls of Heide II, the modernist home-now-gallery designed by McGlashan Everist in 1963 for the artists John and Sunday Reed. Stewart Russell has long been inspired by English botanist and photographer Anna Atkins (1799 – 1871), whose works and techniques he first started to analyse at London Printworks in the 1990s. Atkins is probably the first woman to take a lens-based photograph. Prior to that, her arresting blue and white cyanotypes and “photogenic drawings” of ghostly seaweed were self-published alongside handwritten annotations in her 1843 book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, the first-ever published book of photographic images. Atkins’s direct exposure sun prints of sea and terrestrial botanical species are as beautiful as they are groundbreaking—made by a nineteenth-century woman who had received an “unusually scientific education” for the time, an artist interested in biodiversity who was also unafraid of scientific and technological innovation. Nothing is made in a vacuum: the art and science of today is built on the experiments and breakthroughs of the past. In Spacecraft’s textile design, the silver vein creeper is layered in an Atkins-esque assemblage of gossamer leaves and vines, keeping her pioneering history alive for a new generation.

In the 1980s, Stewart and his partner Donna O’Brien (co-founder of Spacecraft) relocated to Sri Lanka from the UK. They worked with local textile designer and artist Barbara Sansoni, setting up a textile printing studio three hours by motorbike out of Colombo. Stewart and Donna’s print studio and house were designed by Barbara’s close friend and collaborator Geoffrey Bawa, the influential Sri Lankan architect. Living and working in Bawa’s tropical modernism, Russell and O’Brien observed a context-sensitive approach to design—an architecture in which the edges between interior and exterior worlds were porous, where trees, boulders and plants took precedence, and internal courtyards could transform from spaces to eat and entertain into a space for sleeping under the stars. Bawa’s architecture brought the functionality and social practice of Brutalism to the tropical climate and culture of Sri Lanka, with its blend of east and western influences, colonial and vernacular design. For Russell and O’Brien, Bawa’s lessons—on how we can live smaller, more compact, and make architecture fit around nature—were formative.

In his chapter on ‘Pioneers and Aboraphobes’ in The Australian Ugliness, Robin Boyd writes that “Modern Australians have no especially psychopathic fear of the gum or wattle, but no two trees could have been designed to be less sympathetic to the qualities of tidiness and conformist indecision which are desired in the artificial background.” Boyd was concerned with the tendency he saw in Australian cities, suburbs and homes to try to nullify, tame or eradicate nature; to replace the “already-existing” Indigenous plant life and bushland with the “it’s better because it’s old world” European flora. Biodiversity—the variety of life on earth in all its forms—is the most complex and vital aspect of our planet, and we are losing it at an alarming rate. Aside from the cold reality of scientific data that speaks of the growing extinction of our plant and animal life, if we look at biodiversity on a philosophical level, as a kind of shared and accumulated knowledge passed on over millions of years between species on how to survive through varied environmental and existential conditions, we are “burning the library of life”. Experts such as Oxford University’s Prof David Macdonald says: “Without biodiversity, there is no future for humanity.”

That clarion call—to wake up before it’s too late—to relearn how to coexist with nature and non-human life in our cities and suburbs (knowledge Indigenous Australians have never forgotten) runs through the quiet and conscientious work of Spacecraft, engaged as it is with the elemental, the material, the botanical, the artistic, the political and the social.

Film of Spacecraft studio by Mark Newbound

Author

I am an Australian artist of Chinese–Singaporean descent who works across video, performance and installation. In my work, I transform myself into invented fictional personas to traverse through time and cultures to explore how national identities and stereotypes cut, divide and bond our globalised world. Recent projects include The Australian Ugliness (2018), a multi-channel video installation that pays homage to modernist architect Robin Boyd’s book of the same name, while exploring the ethics and aesthetics of our nation today. The work will be presented at The National 2019 and as part of The Ambassador, a tour initiated by 4A Centre for Contemporary Art and Museums and Galleries NSW that kicks off at Samstag Museum (SA) in February 2019. If in Melbourne, Eugenia’s work is currently on show as part of Gertrude Studios exhibition and Lucky? at Bundoora Homestead. In 2019, Eugenia is incoming co-director (with Lara Thoms and Mish Grigor) of Aphids.

I am an Australian artist of Chinese–Singaporean descent who works across video, performance and installation. In my work, I transform myself into invented fictional personas to traverse through time and cultures to explore how national identities and stereotypes cut, divide and bond our globalised world. Recent projects include The Australian Ugliness (2018), a multi-channel video installation that pays homage to modernist architect Robin Boyd’s book of the same name, while exploring the ethics and aesthetics of our nation today. The work will be presented at The National 2019 and as part of The Ambassador, a tour initiated by 4A Centre for Contemporary Art and Museums and Galleries NSW that kicks off at Samstag Museum (SA) in February 2019. If in Melbourne, Eugenia’s work is currently on show as part of Gertrude Studios exhibition and Lucky? at Bundoora Homestead. In 2019, Eugenia is incoming co-director (with Lara Thoms and Mish Grigor) of Aphids.