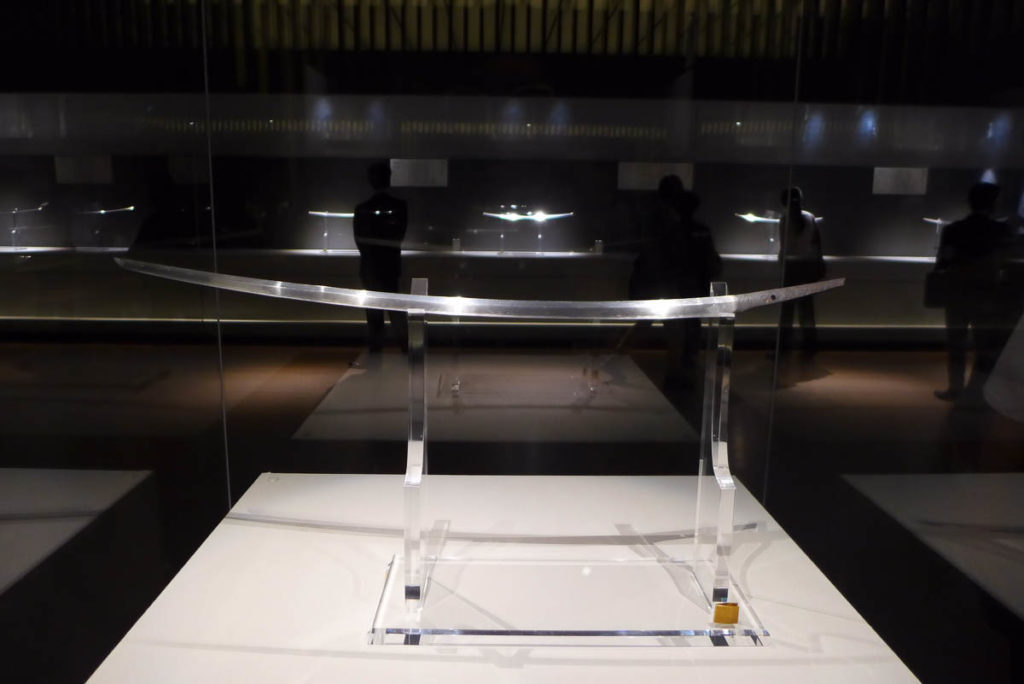

- 国宝 太刀 銘 三条宗近/Sanjo Munechika—National Treasure/The origin of Japanese Style swords by Sanjyomunechika

- Important Cultural Property. Okuni Kabuki. Kyoto National Museum

- National Treasure. Long Sword (Tachi), Inscription: “Norikuni.” Kyoto National Museum

- The exhibition board

- 刀剣乱舞展と刀剣女子—the additional exhibition of Online Game /personified sword character, photo by Sachiko Tamashige

Series of events commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration are being held throughout Japan this year. The present Emperor plans to pass the throne to the current Crown Prince on 30 April 2019, ending the era name of Heisei which was proclaimed the day after the death of the Emperor Showa 30 years ago. With the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo approaching and international attention increasing, publications and exhibitions have been produced one after another, providing opportunities for Japanese people to reaffirm their identity.

Against this backdrop, Swords of Kyoto-Master Craftmanship from an elegant culture, a large-scale special exhibition on Japanese swords held at Kyoto National Museum from 29 September until 25 November, provides abundant inspirations that help explore Japanese identity, closely links with their way of monozukuri, or attitude of making things with belief that gods or a good dwell in ultimate things.

Since Japanese swords were perfected with peculiar curved form about 1000 years ago. They have been through many changes throughout the history of the country with the transformation of the political and social systems. They have been considered as a sacred treasure since ancient times. What swordsmiths craftsmen have achieved through Japanese swords as strong weapons are three points: they do not break, nor bend, and cut well. But the craftsmanship also transcended them as a piece of art with three points to appreciate: sugata (the shape), jigane (the steel patterns) and hamon (the temper patterns). In addition to their function as a weapon, people have worshipped their gleaming, beautiful forms for their sacredness and symbolism and appreciated them as artworks, associating them with various folktales and legends since ancient times. Many of the Japanese idioms have derived from the words related to swords such as “Aizuchi wo utsu (to chime in)” which came from the scene of two people alternately pounding on a blade with a tsuchi (or zuchi) as if responding to each other, and “Shinken shobu (serious battle)” with shinken meaning “real sword” and shobu meaning “battle.”

As represented by The Imperial Regalia of Japan, the Three Sacred Treasures—a mirror, a jewel and a sword—swords have also been regarded as the proof of a sovereignty that is endowed by the gods as well as sacred offerings to the gods. Craft masters poured their souls into making such treasured swords of high perfection. This reflects the Japanese way of thinking, based on Shintoism, or animistic cosmology where a good dwells in things which are made perfectly with the whole-hearted dedication of craftsmen. Although swords are weapons originally, Japanese swords, with perfect clarity and beauty, became to be treated as talismans to ward off evil spirits. Japanese swords are a quintessential example to explain the national characteristics of Japan, including its aesthetics, mentality and skills and attitude that support the manufacturing of sophisticated fine arts and crafts.

The Meiji Restoration brought about modernisation that caused drastic changes in the society, ending the samurai era in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After Haitorei, a decree banning the wearing of swords, was issued in 1876, samurai carrying swords disappeared from the streets and many craftsmen who had engaged in the process of making swords were forced to go out of business. Yet a small number of sword craftsmen have kept the tradition of swordsmithing alive until today.

“This special exhibition sums up the history of ‘Yamashiro-kaji (sword smiths of Kyoto)’ from the Heian period to the present day. The characteristic of swords made in Kyoto is the gracefulness in the curvature of the shape and the steel patterns. It is not just a type of weapon, it is also the extract of the exquisite sensibility and aesthetic sense of the Japanese people. I hope you activate the DNA in your body that you inherited from your ancestors to appreciate the exhibition,” said Johei SASAKI, the director of the Kyoto National Museum in his greeting to mark the opening of the exhibition.

“It is the biggest exhibition of Japanese swords of all time in Japan. As many as 177 works are exhibited, including the 19 that have been designated as national treasures: the oldest spear in Japan, halberds owned by the Naginata-hoko Hozonkai (an organization that preserves floats decorated with halberds) of the Gion Matsuri festival, and other works that were found and reported some time ago but have never been open to public with their background information. It really is a special exhibition showing many works that are exhibited for the first time,” said Toshihiko SUEKANE, the curator of the museum who planned the exhibition.

Swords originally came to Japan from China and the Korean Peninsula. Then, since before the Kofun period (tumulus period) from the end of third to the seventh century, straight swords of the Chinese continental style had been made in Japan. The curved Shinogi-zukuri (ridged style,) the origin of the Japanese-style swords is said to have been made for the first time by Amakuni, a swordsmith in Uda-gun, Yamato Province (Uda City in Nara Prefecture today) in the middle of Heian period (late tenth century,) though it has not been proven. One can say that Japanese swords took its form about 1,000 years ago.

“It is impossible to define exactly when the Japanese-style swords were invented, but it is closely related to the rise of samurai warriors in the late Heian period. In Kyoto, the school of Munechika SANJO, the ancestor of Yamashiro swordsmiths, was formed around that time. From there, the history of Yamashiro swordsmiths that expanded for 800 years started,” said Suekane.

Since the capital was transferred to Kyoto in 794, it has been home to the workshops of many swordsmiths, producing a number of noted swords from the Heian period until today. Yamashiro swords produced in Kyoto have always been the most prestigious swords in Japan, appreciated by both court nobles and samurai families. They were also used as gifts as well as tea utensils exchanged between feudal lords and samurai families.

Among the five locations famous for swordsmithing, Yamashiro (Kyoto,) Yamato (Nara,) Bizen (Okayama,) Mino (Gifu,) and Sagami (Kanagawa) that are grouped as “Gokaden,” this exhibition features Kyoto—Yamashiro—swords and explores the swords’ history, technological progress, culture and impact on the society.

In the centre of the second hall of the exhibition, Long Sword (Tachi )(Meibutsu: Mikazuki Munechika, Heian period/Tokyo National Museum), which is a national treasure shows a strong presence as one of the early works of Japanese-style swords and the origin of Yamashiro swords. Takaki KOSAKA also known as a producer Digitarou was drawn into this sword. He is the producer of “Touken Ranbu –Online–,” a simulation game to develop swords, which has become an inspiration for the sword boom. “In the game, many noted swords are personalized. All of them are the main characters, but Mikazuki Munechika is special. It is illustrious and iconic as it is the origin of Japanese swords,” said Kosaka. The belief that spirits live in tools and goods is rooted in the Japanese culture since ancient times. The personalisation of swords may be modern expression of such belief. There are even Tokenjoshi or Swords Girls, female fans of swords many of whom became attracted to swords through the online game. They flock to sword exhibitions as if to go to idols’ concerts.

In Kamakura period (1185–1333), the demand for swords soared with the rise of samurai. Emperor Go-Toba established Goban Kaji system to secure imperial swordsmiths and promoted swordsmithing, creating the golden age of Japanese swords. The Heian period ended when the Heike clan was defeated by an army of the Genji clan in the naval battle of Dannoura. It is said that Emperor Antoku, related to the Heike Family by blood, and who was still a child at the time, drowned himself at the battlefield holding the sword which was one of the Three Sacred Treasures.

His younger half-brother who took over the throne from him was Emperor Go-Toba. It is said that the loss of the sword that had been succeeded within the Imperial Family motivated Emperor Go-Toba to invite a different swordsmith monthly to work in the workshop inside the imperial palace while the emperor himself also made swords.

The truth is unknown, but the story about Emperor Go-Toba and the imperial swordsmiths raised the social status of swordsmiths who used to be just a type of skilled workers. Those swords made by the imperial swordsmiths are referred to as Kiku Gosaku because they have a kiku (chrysanthemum) engraving, the imperial crest, on their tangs. They reflect the special position of Japanese swordsmiths connected with the ruling classes of the country.

Japanese swords have continued to develop pursuing the achievements of three factors at the same time: not break, not bend, and cut well. Many swordsmiths have devised ways to manufacture raw steel, select and forge the steel since ancient times. The legitimate Japanese sword is made from Japanese steel “Tamahagane”. As a Japanese sword is composed of two parts, shingane (a soft inner core) and kawagane (a hard outer jacket), which are fold-and-forged individually and then combined so that the combination of soft and hard steels enables the sword to absorb the shock of impact of fighting without breaking. After the blade with clay applied on the surface is heated and quenched in water, the hamon, the temper patterns, appear in the hardened edge. Then a sword is polished with different grades of polishing stones by a professional polisher. The methods of sword making differ by the school of swordsmiths in different areas. A connoisseur of Japanese swords can tell an area of production, period and name of swordsmiths when he appreciates the sword.

“The characteristics of Yamashiro swords are the quality of steel and the traditional elegance of tempered blades. Swords made in Kyoto are unrivalled in terms of gracefulness and artistry,” Suekane stressed. The group of swordsmiths who settled in the district of Awataguchi in Kyoto (south of Okazaki on the south side of Sanjō-dōri today), since the beginning of the thirteenth century, is called the Awataguchi school. Six artisans from this school are said to have served Emperor Go-Toba as the imperial swordsmiths. An outstanding craftsman, Yoshimitsu, who consummated the study of steels, is also from this school. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the ruler of the country during the sixteenth century, who had a passion for swords, is said to have referred to Yoshimitsu as the head of the top three swordsmiths in the country.

The disciple who studied under one of Yoshimitsu’s disciples was Masamune from Soshu (Kanagawa), whose swords were also craved for along with Yoshimitsu’s by many of the feudal lords. Ownership of such noted swords helped raise the status of a family, and the fact that historically important people and families owned the swords further added value to the swords in return. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who established the Edo shogunate which lasted over 260 years since 1603, was also an owner of many noted swords.

The Honami family that monopolised the sword appraisement business since the Momoyama period (1573-1603), also polished swords and produced fittings with craftsman with various skills. During the era under the rule of the eighth Shogun, Yoshimune TOKUGAWA, the Honami family is said to have written Kyoho Meibutsu-cho, a record of noted swords, which had an impact on the selection of national treasures in later years. Koetsu HONAMI, born in the Honami family, had interests in calligraphy and pottery and collaborated with Sotatsu TAWARAYA, a renowned painter and designer in establishing the Rinpa school, one of the major historical schools of Japanese painting. This is an example of how swords and arts were closely related: those who have an eye for swords have an eye for arts and crafts.

During the peaceful and stable Edo period, in which there were few battles where swords were actually used, artistic swords with more emphasis on decorations were made. This is how the swordsmiths who had lost their jobs when Haitorei (decree banning the wearing of swords) was issued, managed to make a living in the field of crafts such as making Japanese kitchen knives and metalworking. Metalsmiths who attracted global attention with their sophisticated techniques at world expositions during the Meiji period were originally craftsmen related to swordsmiths as well. Edged tools including kitchen knives and scissors made in Sakai in Osaka Prefecture and Seki in Gifu Prefecture are highly evaluated internationally. The DNA of the swordsmiths who dealt with materials earnestly and poured their spirits into forging and polishing swords is still alive in the manufacturing scenes of the present day.

The way of using Japanese swords in contemporary days:

The Three Sacred Treasures will play an important role in the series of ceremonies that will take place when the present Emperor transfers the throne to the new Emperor next year.

Swords are still the symbol of sovereignty. Although they are not used weapons anymore, top players of Kendo (art of fencing) and Iaido (art of drawing a sword) still use real swords from time to time with utmost care not to hurt the opponents. There are sword lovers and collectors in Japan and abroad whose occupations vary from martial artists and wrestlers to designers. There is no rule as to how to store swords; some people place them on stands or hang them on the walls, and others keep them in scabbards and bags. It is the elegant curve of a Japanese sword that many people are attracted to.

On the other hand, the deep shine of Japanese swords is achieved by skilful polishing. Therefore, polishing techniques have been highly developed together with the techniques in making swords. The styles of swords reflect the times and the finely polished steel and various blade patterns represent the origins and schools of the swordsmiths. Not only the glow of perfection but also the history and background story of each sword continues to mesmerise sword lovers. When one encounters the breathtaking beauty and clarity of the gleaming surface of Japanese swords, one cannot help feeling clear, up-lifted and sublime.

The special exhibition “Swords of Kyoto-Master Craftmanship from an elegant culture” was at Kyoto National Museum 29 September to 25 November

Author

Sachiko Tamashige is a Japanese freelance journalist based in Kyoto, she has been working for various media such as broadcasting companies such as BBC, NHK, as well as the newspapers such as Japan Times, Asahi Shinbun and female magazines etc. specialising in culture such as architecture, design and art. The style of writing is to put any kind of theme of culture in social-historical context. If you would like to read any of Tamashige’s article in English, google Sachiko Tamashige, Japan Times, such as Seeing where Shinto and Buddhism cross.

Sachiko Tamashige is a Japanese freelance journalist based in Kyoto, she has been working for various media such as broadcasting companies such as BBC, NHK, as well as the newspapers such as Japan Times, Asahi Shinbun and female magazines etc. specialising in culture such as architecture, design and art. The style of writing is to put any kind of theme of culture in social-historical context. If you would like to read any of Tamashige’s article in English, google Sachiko Tamashige, Japan Times, such as Seeing where Shinto and Buddhism cross.