- Elizabeth’s knitting needles, photo: Boaz Nothman

- Elizabeth and her Knitting Needles. Repaired by Kyoko Hashimoto and Guy Keulemans. Photo: Lee Grant. Courtesy Hotel Hotel.

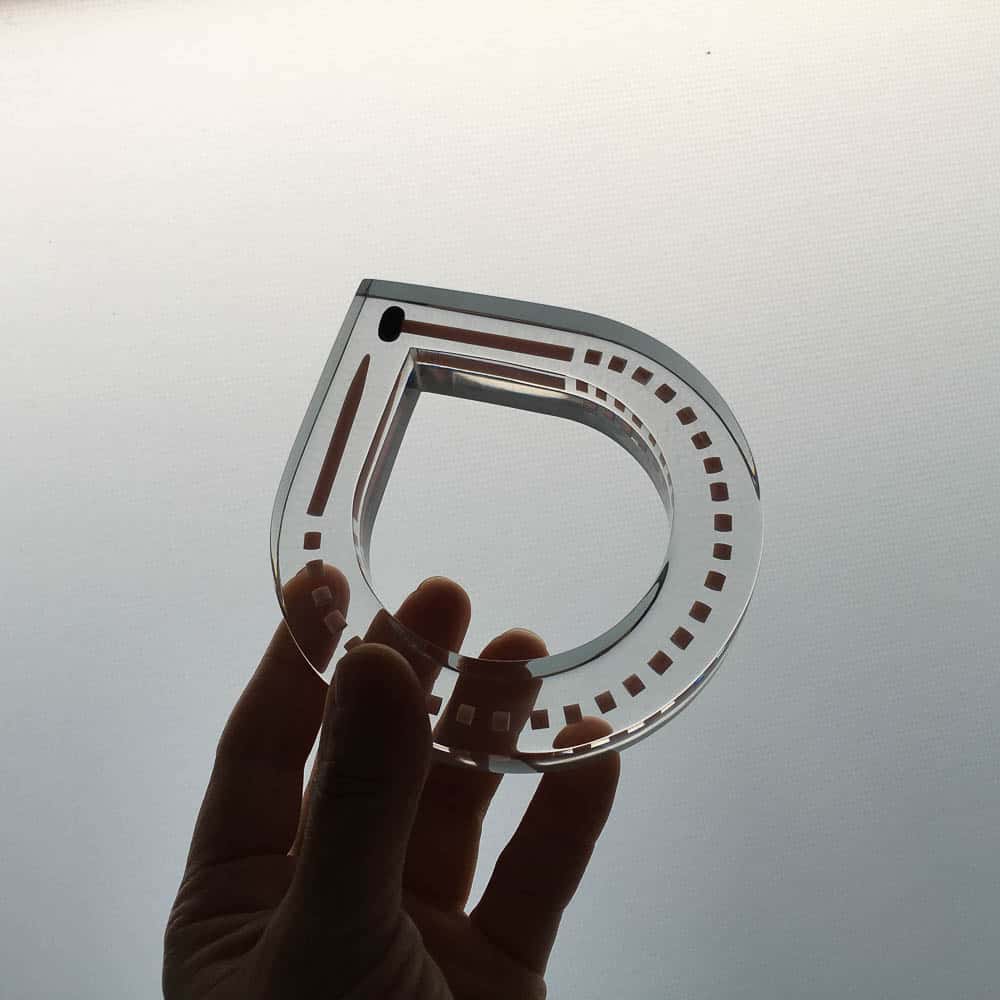

- Knitting Needle Bangle on Yellow-Blue

- Guy Keulemans, photo by Dean McCartney

- Kyoko Hashimoto, who designed the piece with Guy

As part of Object Therapy, an exhibition currently on display at the Australian Design Centre, Elizabeth Macky’s broken knitting needle was creatively transformed by designers Guy Keulemans and Kyoko Hashimoto in a project exploring memory, meaning, repair and waste.

When Elizabeth Macky first snapped one of the knitting needles her grandmother had bought for her as a child, the first thing she did was put them in the bin. “I threw them out for about 20 minutes and then thought, ‘I can’t do that, I’m going to have to do something with them.’ So I went and got them back out of the bin and cleaned them off. They were sitting on my desk for quite some time while I worked out what to do with them next.”

After seeing a call for expressions of interest, Elizabeth was one of 29 members of the public selected to submit broken objects for transformative repair as part of Object Therapy. For Elizabeth, the knitting needles were special—her grandmother had bought them for her at around the age of six or eight, and over the intervening 35+ years she had used them, on and off, for special projects, like the ANZAC Day poppies she was knitting the day she broke them. “I’d taken them with me to have lunch with a friend,” she explains. “To eat, I shoved everything into the bag and underneath, and I felt resistance and thought, ‘I’ve just snapped them’.”

In pink plastic with black knobs, one needle remained intact, while the other was broken into four pieces, making them unusable. But they still had meaning for Elizabeth. “They were from Gran and it’s a link back to her. She’s gone and I wanted to preserve that link,” she explains. “I’ve got… more precious things from her. This was just an everyday thing between a grandmother and a granddaughter, passing on that thing that Gran loved—the knitting.”

As part of Object Therapy, Elizabeth’s knitting needles were assigned to Guy Keulemans and Kyoko Hashimoto for transformative repair. Keulemans, a designer and repair researcher at UNSW Art and Design, and Hashimoto, a jewellery designer, set to work on a solution. “It was that emotional attachment that was significant for us. We picked up on the story of Elizabeth’s grandmother and the idea of years going by,” says Keulemans. Hashimoto continues: “Originally I thought we’ll cut it into pieces and put it together like a mosaic and make it into a brooch, but then if you do that, you lose that it was a knitting needle.”

Instead, the pair came up with the idea of a bangle, with the needle set in clear resin as a wearable piece of jewellery. By further slicing the needle into smaller pieces, the visual language reads as an ellipsis (…) referring to the generations, yet because of the way it is set in a loop, it also still reads as a knitting needle. “I felt when we first got it, that we have to turn it into some kind of an heirloom,” says Hashimoto. “I wanted the object to live on as something she could hold onto.”

The finished result combines the talents of Hashimoto, who had some experience casting precious items in resin from her earlier jewellery work, with Keuleman’s research into transformative repair. Keuleman sees the exhibition as a design methodology that connects one community with another, relating to his research into ‘constructing publics’, a concept developed from John Dewey by Carl DiSalvo and new materialism theorist Jane Bennet. “I always saw this as a design methodology for an exhibition,” Keuleman says. “In some ways, it’s related to critical design, which is about critiquing the modes of practice of the industry and production. It’s also a participatory design model because it’s getting the public involved and lastly it brings in the demographic model, which is taken from social science.”

Object Therapy was developed as a series of events within the Fix and Make cultural program of Canberra’s Hotel Hotel, tapping into a burgeoning interest in making and repair that counters the fast consumerism of society, which today sees objects more likely to end up in landfill after just a couple of years. While advanced industrial production methods have lowered prices to allow lower-income individuals to enjoy a better standard of living, these low prices also lead to an increasingly wasteful throw-away society.

In reaction to this, repair is fast gaining popularity. Keulemans has dedicated his research career to the topic and sees functional repair, but also more creative solutions, as the way forward: “I think it’s really amazing what artists and designers can bring to the practice of repair. It’s really different from functional repair,” he says. He points to Sweden as global leaders in recycling and repair policies, where, significantly, you only pay half the goods and services tax on anything that’s repair related. “It could happen in Australia. I don’t even think it’s not happening because there’s resistance, I think it’s not happening because it hasn’t been in the policy domain. It really does come down to people pushing it and saying ‘let’s make some changes here’.”

As for Elizabeth, she is very happy with her new knitting needle bangle. And the whole process has also inspired her to think more about repair: “I’ve thought about other stuff at home that was otherwise broken or not as pretty or attractive, and I’ve already fixed… a washing basket, which I’d repaired with a piece of string so it didn’t break, but it’s much prettier now.”

Author

Penny Craswell is a writer, editor and curator with a specialisation in design and architecture. She is Creative Strategy Associate at the Australian Design Centre and is currently working on a new self-initiated print publication called The Milan Report 2017, which is a review of this year’s Milan Furniture Fair. A former Editor of Artichoke magazine, Penny contributes to design magazines worldwide, including Frame, Mark and Azure. Her blog is The Design Writer.

Penny Craswell is a writer, editor and curator with a specialisation in design and architecture. She is Creative Strategy Associate at the Australian Design Centre and is currently working on a new self-initiated print publication called The Milan Report 2017, which is a review of this year’s Milan Furniture Fair. A former Editor of Artichoke magazine, Penny contributes to design magazines worldwide, including Frame, Mark and Azure. Her blog is The Design Writer.

Object Therapy is showing at the Australian Design Centre (ADC) in Sydney until 7 June and is part of ADC On Tour, the Australian Design Centre’s national touring program. ADC is partnering with Hotel Hotel for the first time to develop and deliver an eight-venue national tour supported by the Australian Government’s, Visions of Australia (Visions) program.