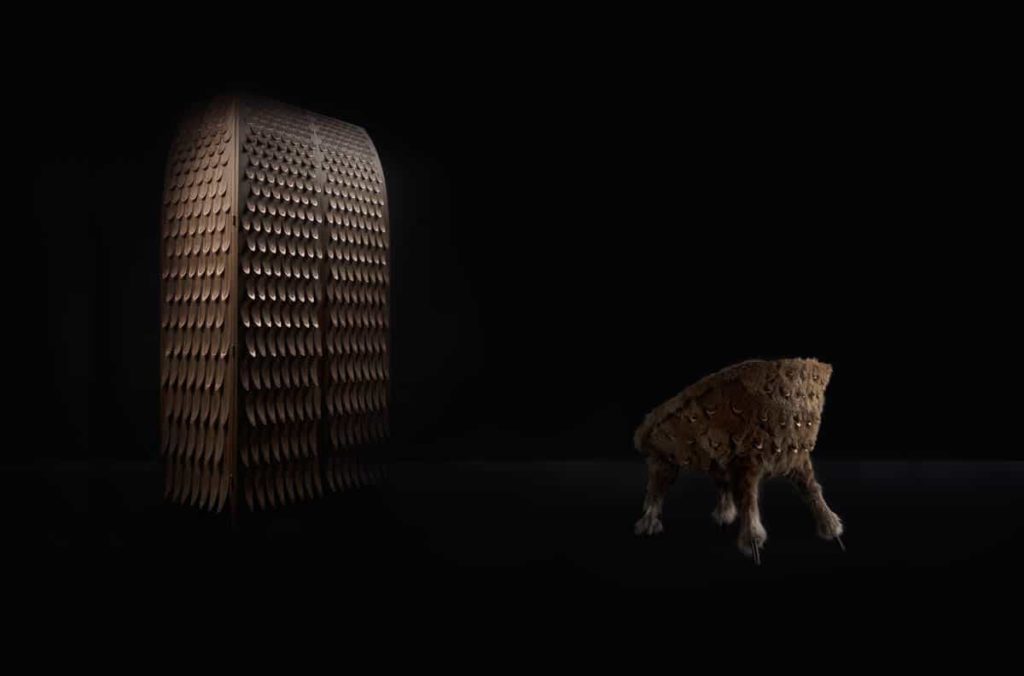

- Trent Jansen, Pankalangu wardrobe and chair

- Trent Jansen, Pankalangu wardrobe

- Dan Hocking and Trent Jansen at Criteria

- Dan Hocking and Trent Jansen

- Dan Hocking and Trent Jansen

Lou Weis has been a critical influence in the recent development of design as an art form. As creative director of Broached Commissions, he has orchestrated an original series of editioned designs that tell thoughtful stories of historical resonance. Garland finds Lou Weis at his new showcase, Criteria, where he narrates the vision that has guided this venture. This involves a precarious balance between creative integrity and the market that makes it all possible.

✿ What prompted Broached Commissions?

Broached emerged from a consultancy to the Australia Council in 2006-2007 for externalising a grant called Maker-Manufacturer-Market. I decided to call them “entrepreneurial makers”. They were object designers, usually designers by trade, but struggling to find manufacturers and took it upon themselves to produce. The grant was to find a pathway for making.

Australian Design Unit was set up and $400k was raised. And then, because I showed results, the Australian object design scene noticed that, and I got a call from Trent [Jansen] and Adam [Goodrum] when I returned to Melbourne asking would I help them organise an exhibition of their prototypes and exhibition pieces. There was no narrative to it. I said that sounds really boring [laughs] and could I help. I’m frank and friendly!

Then Geoffrey Nees, the artist, introduced me to the antique house Wally Johnsons Antiques & Collectables, who had the right to use of all timber that falls in the Melbourne Botanical Garden. I saw it immediately as a postcolonial narrative; that the timber should be utilised by the best artisans, designers and curators. The owners of the antique house disagreed with that view, and declined the offer to create a brand around it, then I realised that Trent and Adam’s desire for an exhibition and my creative direction of a post-colonial narrative didn’t need to be mutually exclusive. We didn’t need heritage timber. We just needed good research into the history of applied arts in this country. And [we needed to] to pick a moment, like the Botanical Gardens had created, and develop new work that told a story about how the applied arts flourished according to different periods in Australian history.

✿ So where did the name come from?

I had this really crappy name called Knotted and everyone hated it. It came out of that timber conversation. “Broached” came about because of the multilayered meaning of the word when applied phonetically. A brooch is a small object on a larger body—we were making a humble contribution to a much larger body of work. To “broach” is to push through the surface (meaning). And finally “to broach” a subject matter that had become taboo or long overlooked. For instance, colonial period applied arts had become encrusted in fallacious cliches—red cedar and make do furniture—which don’t bear out the enormous ingenuity and incredible wealth that was accumulated in that period or the extent of trade. So we pushed through the surface meaning of the colonial period and “broached” social issues of the period that people do not usually associate as being within the realm of furniture design.

This is where my scepticism towards the progressive nature of design becomes relevant to the project. Design sells itself as a panacea to the problems of society. It’s a problem-solving industry. My view is that design is a tool of industry, the best ideas of which are quickly commodified. Whatever good intentions may have been in the beginning are quickly stripped out by the marketplace, which is only interested in scalability. Modernism is the classic example of that.

✿ So you see commodification as a negative process?

Mostly. It’s privileging of modernity and speed over fidelity of our material culture. You can see it in music over the twentieth century, which has gone to the highest possible fidelity in a [vinyl] record to the lowest possible fidelity in MP3. When I was a kid, it was still normal to buy a record, just. Then we all started buying cassettes, CDs, then mini-discs. So we’ve bought potentially four different versions of our favourite record in the first 30 years of our lives. That’s the marketplace selling mobility over quality.

✿ So is editioning for an elite market something that retains fidelity?

One solution is products that have built-in obsolescence. When I lose my hardware, the phone is redundant. It is insured so I get another one for free. The data keeps me mobile and connected to more data. The idea was you would buy a stereo when you become an adult of means, and that stereo is probably not replaced for 10-20 years. Now it’s commodification combined with consumerism in league with fastness…

We automatically editioned all work in our first series. Over time, we simply started applying a simple rule: if the object is extremely painful to make, it will be an edition, in that no one wants to keep making them. The marketplace probably won’t bear the real cost, even if we keep raising the price as they sell, which rewards the early adopters. If it is relatively simple to make then it is an open or much larger editioned work.

✿ Editioned design seems to be something often found in the burgeoning scene of international design fairs. Who do you think is the primary audience for these?

[Design fairs are] the Bunnings of collecting. It’s everything under one roof. The collectors get to fly from wherever they are in the world and see everything in one hit. What gallerists tell me is that sometimes they sell really well, sometimes they don’t, but they get to see what other people are selling and buying, which is valuable to them. They get to price check their pieces against others. A lot of people leave feeling emptied out. It’s the opposite of what we set up these companies to do, which is to create intimacy between the individual and the object. And a lot of that is about how the work is shown, and you can’t do that in an aircraft hanger, where all your competitors are cheek by jowl next to each other. It’s about who’s got the biggest booth and the prettiest women and who’s got the champagne. It’s about commercialisation rather than a dialogue about the history and contemporary meaning of material culture.

✿ So broadly, what’s the spectrum of audience? Does it include institutions or curators?

A lot of specifiers, a lot of curators from the major museums and galleries, and collectors.

✿ Do they buy for investment?

If you have the pie chart of motivation, investment is 20-30% of motivation. High net worth individuals are turned on by good ideas, executed well.

✿ What’s the difference for you between someone who collects art and design?

They tend to be collectors of both. Art is more emotive. It is designed to stimulate a way of re-thinking reality or their emotional state. And this little world of object design is about how they relate to the functional objects in their daily life and their emotions in that. It can have a humorous element to it. There’s also a great appreciation of craft in contemporary edition design. I notice that objects which do well manage to clearly convey the difficulty of making. In conceptual art, the making has been removed.

For people like Ai Weiwei, the craft of making is still very strong in their practice. But there are many successful artists where that is not the case.

✿ The Parallels design conference at the National Gallery of Victoria (September 2015) set up to examine that world and put Melbourne in the circuit. Is there a reason for Australia to aim to be part of it?

It’s such a small world, even internationally, compared to the visual arts one. If you look at it broadly—not as broad as hardcore industrial design, like the traffic pedestrian buttons, which is a great achievement and has ideological elements of egalitarianism that is successfully integrated into manufacturing form. But if we limit the exhibition to intimate forms of design and craft fabrication, I would have thought that there is scope to have a very large Triennial of that work from all over the world. There wouldn’t be many other examples of it. But the objects we have around us [in Criteria] like the Monsters have a very small market. If the NGV gets behind that, and they are a little with the upcoming triennial, it might slowly grow a taste for that work. Ultimately you need a local gallery circuit supporting it, and there isn’t one in Melbourne or anywhere in Australia

✿ You’ve taken Broached into that circuit. How has it gone?

Mixed. We had two shows in Dubai. We’ve been well received locally and internationally. There’ve been two issues. First, the speed with which we’ve been able to get new pieces into the marketplace and the difficulty I’ve had in establishing presentation platforms. This show with Criteria has saved me having to “pop up” every time or operating a permanent space of my own. Criteria is a commercial showroom with high-end production studios, Apparatus and Baxter, at the top end of furniture manufacturing. We fit well there, but we are much more kooky than those pieces are. Our work is much more about bending a historical, almost antiquated form into the present. It’s got a gnarly quality to it. It’s like a homunculus in the corner of the room.

✿ Are there design collectors in Australia?

A few. Because there’s only a few here, and because the market is not organised around a network of galleries, we immediately consider the work we are making within the international marketplace. Logistics becomes important from the outset. So the Broached MONSTER wardrobe, for instance, is very large and very hard to move—250 kilos. It’s probably not going overseas. We spent a lot of money making that. The opportunity to find the eccentric single person worth $100m in New York or LA or Dubai or Basel is far higher than it is here, where the average person is married with one child in the suburbs by 28. You’re still young in New York if you’re 40 and single.

✿ Do you have a sense of who the collectors are?

The buyers from the first collection tend to be entrepreneurial people in the peak of their acquisitive state. So they are building the stories of their companies and they are very attracted by the nature of their daily occupation to objects that tell strong stories and attract media and community to it. So that’s what they’re doing. So Broached is successful in two ways. We’re selling a media story, which is a discussion point about Australian history, so that’s broadly acceptable. And we’re selling physical objects that are narrowly accessible. So they find that quite exciting. And often they end up ask “Can you do this for me?” We end up getting swallowed up in their own desire to take thoughts and make them manifest and tactile.

✿ So you are looking for an adventurous client?

Some patrons are really clean in those transactions and let you go about your business and understand that the outcome is a risk. And others, not that they are aggressive, are bound up emotionally with problems that are at the heart of creativity, but for them they are personal problems. It’s like for those people that you’re helping them fill their soul. They’ve got something missing. And they think that these commissions will help heal them some way. And they’re the worst.

✿ What happened with their soul? Did they sell it or did they lose it due to a traumatic experience?

All those things. It’s often a refugee community, mine included, who had to suffer great things and strive for the enormous level of independence that wealth achieves. And then the next generation tries to reconnect with some narrative of place. That can be an overwhelming undertaking.

✿ That’s where you locate yourself?

Yes. I would love to not have patrons. I would love to be able to sell to people at a price point where it was easy for them to make the decision. And if a leg got wobbly and they brought it back we fixed it. But the space we’re in at the moment… we have to have them.

✿ Does the “problematic” patron identify with the work?

They see it as solving an emotional connection problem and it never can. It’s impossible to satisfy existential angst. People get high just to blur it out occasionally. There are different kinds of patrons and they can be great. I’m reminded of that scene in Andrei Rublov by Tarkovsky where the prince gets wind that his artisans are going off to his brother’s castle, and you hear them in the forest talking about how they are going to do an even better job there. And he sends his men off to blind them all. Some of the contracts you’ve got to sign…for all this wanting to support great design, they behave like the prince who doesn’t want to share his artisans, but nor does he keep paying them.

✿ You seem to be talking about money as a necessary evil, a wolf at the door, someone you need to flatter…

Not all, but some. Some clients are as clean as can be and entirely pragmatic about taking a risk on the experimental process.

✿ If you had a divine patron, who would allow you to do what you wanted to do, without any condition, would there be anything you would miss from the market?

This is a subject I’ve only just started investigating, which is the master-slave dialectic. Even if you are writing your own book, there’s the master inside you saying you have to make the deadline, you gotta make this real. And there’s the creative one saying, I just need to go for an hour-long walk, I need to just think, let’s not tie it down yet. It’s the same with the relationship between the client and the creative. The client thinks they need to set a realistic budget and control the outcome and process and set “hold points”, as they are known now, when they can check in on the process. And there’s the creative who believes that’s all antithetical to a good outcome. But the creative knows that they can’t do any work without the master. And the master knows if they hold on too tight to the slave, he won’t be able to do any work that’s essential to feeding him. It’s always a fine balance, even if you are doing a project for yourself. You still have an internal master that requires servicing. It’s your own expectations of yourself and your need for discipline.

✿ Is there any master apart from the market?

I feed Broached with the money that I earn from consulting. It means that my family doesn’t go on holidays and I don’t take breaks very often. I might get two weeks a year. That’s still a very bourgeois expectation, I understand that. But it’s a sacrifice nonetheless…so is Broached the master, possibly! Haha.

✿ So Broached isn’t for the money.

No

✿ But money’s still integral to its function.

It has to. And I think as the collections grow over many years and individual pieces continue to appreciate, the overall project will acquire value. We’re only five years in, still a young company. For the moment, it’s pretty much entirely for the love. 70% for the love. I want to have a great CEO working with me who sets strategies, sets a certain path forward, and controls my desire to put everything towards a creative outcome, to what those strategies can achieve. I’ll just spend everything making it beautiful and as perfect as I can, and I’ll hold off launching for a whole year just so everyone has more time to develop the work.

✿ Going back to the story, and your understanding of fidelity, can you say what it is true to?

One of the great criticisms that the baby boomers had of Generation X, which is my generation, was that compared to them we were devoid of ideological focus or fidelity. I think there is a need in this moment, in which neoliberalism is dying and climate change is critical, to have a clear political agenda. And an understanding of what the spreading of the industrial revolution has done. And just to keep designing pretty things because you think there might be a market for it is not really good enough, for me. To have some ecological, humanitarian, egalitarian principles and to be discussing those in a sensible way. This is what we did and we’d like to present this in some way.

Author

Lou Weis is the creative director of Broached Commissions an object design studio that has the history of globalization – the objects and blended cultures it has created – as its focus. Broached has created four collections since founding in late 2011 and is set to launch its fifth collection MONSTERS by Trent Jansen in mid-2016. Lou is also a creative strategist for corporate clients including Misschu, UTS design faculty, Platform Strategy Asia and Molonglo Group to name a few clients from 2015. Lou is also co-founder of The Welcome Committee, which is agitating for a change to refugee mandatory detention policies in Australia.

Lou Weis is the creative director of Broached Commissions an object design studio that has the history of globalization – the objects and blended cultures it has created – as its focus. Broached has created four collections since founding in late 2011 and is set to launch its fifth collection MONSTERS by Trent Jansen in mid-2016. Lou is also a creative strategist for corporate clients including Misschu, UTS design faculty, Platform Strategy Asia and Molonglo Group to name a few clients from 2015. Lou is also co-founder of The Welcome Committee, which is agitating for a change to refugee mandatory detention policies in Australia.