- Jakkai Siributr, Bannasan Tribe #3, 2016, Digital Print, 120×80 cm

- Jakkai Siributr, Bannasan Tribe #5, 2016, Digital Print, 120×80 cm

- Jakkai Siributr, Bannasan Tribe #2, 2016, Digital Print, 120×80 cm

- Jakkai Siributr, bannasan Tribe #4, 2016, Digital Print, 120×80 cm

- Jakkai Siributr, Bannasan Tribe #1, 2016, Digital Print, 120×80 cm

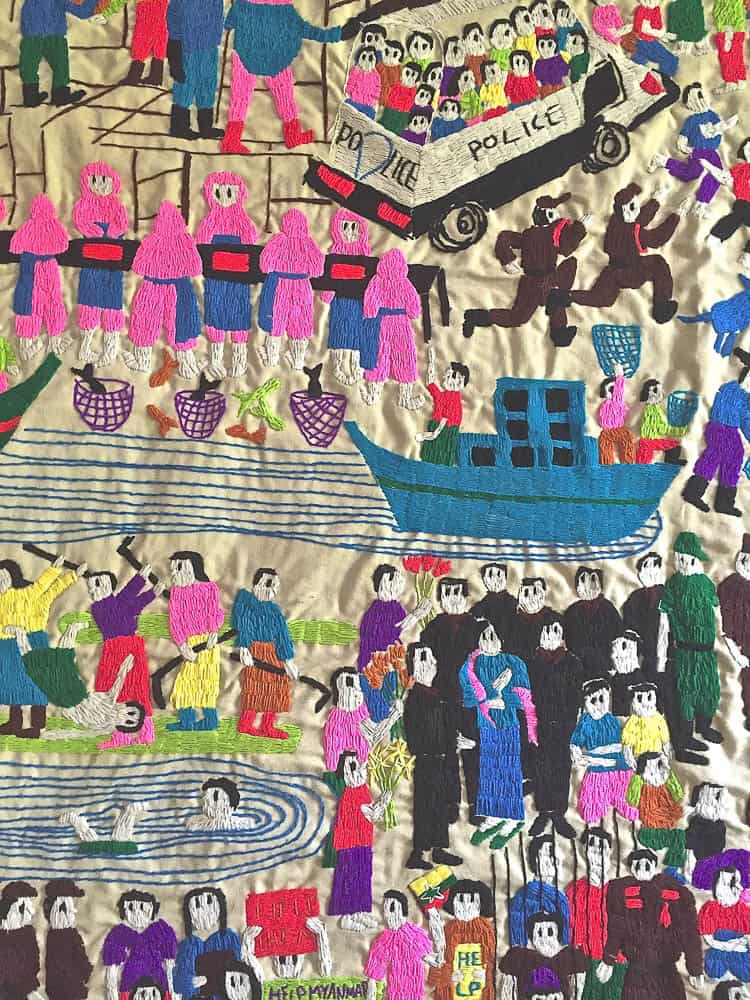

- Jakkai Siributr, Jakkai Siributr, IDP Story Cloth, 2016, Hand Embroidery

- Jakkai Siributr, IDP Story Cloth, 2016, Hand Embroidery

- Jakkai Siributr, IDP Story Cloth #1 (Details), 2016, Hand Embroidery, 150×290 cm

- Jakkai Siributr, IDP Story Cloth #2 (Details), 2016, Hand Embroidery, 150×290 cm

- Jakkai Siributr, The Outlaw’s Flags, 2016, beads and fabric, dimensions variable

- Jakkai Siributr, The Outlaw’s Flags, 2016, beads and fabric, dimensions variable (Through 21 invented “flags” —embroidered seeds and beads on Burmese longyi and monks’ robes— unclaimed by any nation, the artist points to the perniciousness of nationalism that with its boundaries and exclusions, is often used to excuse abuses of power.)

- Jakkai Siributr, The Outlaw’s Flags, 2016, beads and fabric, dimensions variable

- Jakkai Siributr

This work, titled IDP Story Cloth (International Displaced Persons), takes its inspiration from the story cloth of the Hmong Laos people who emigrated to the US in the 70’s. Their story cloth often depicts scenes of a village life as well as their journey to escape the conflicts in their own country.

The IDP Story Cloth tells the plight of various ethnic minority groups in Myanmar that end up in Thailand as migrant workers. Some of the images come from newspaper clippings as well as the internet. Some are from my research trip to Myanmar and the rest are drawn up from my extensive reading on the minority groups as well as talking to a few of them that are now working as my assistant and domestic worker. For the three panels, I first sketch onto the cloth and each assistant then embroiders it. So each panel is very specific to that person’s style of embroidery.

The IDP series in fact is comprised of three components. Together with these panels, there are five photographs as well as garments.

For the photographs, I have used real migrant workers as models. They are wearing garments that are made specifically for this project. At first glance, the garments are supposed to look like normal hill tribe costumes, instead they are embroidered with different materials such as bullet shells. The models are placed in a modern environment doing their daily chores.

I wanted this whole series to have an ethnocentric qualities—the story cloth, the costumes, the photographs, but with a contemporary twists.

The visit to Myanmar was specifically for a research trip for the works about Rohingyas in which the flags are the result. So I spent a week in Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine state. In the vicinity of Sittwe is where a large number of Rohingyas start their sea voyage to escape the violence. It is also where refugee camps are located. I did not visit the camps since it was off limits, but during my stay in Sittwe, I saw the remnants of events which took place a few years ago—burnt mosques and buildings, etc.

After that trip, I went to Ranong in the south of Thailand. This is the first land mass for these refugees to come ashore and then be trafficked onto Malaysia and other third countries. Those who did not survive the trip are often buried in an unmarked grave, which I’ve also visited.

Because of the proximity to Myanmar, there are many migrant workers living and working in Ranong. And this is how the idea of IDP series came about. My visit to Sittwe was very depressing.

The people that worked on the embroidery are my full time assistants. One is from Myanmar, the other two are Thais. I drew the outline with colour coded markers and they embroidered accordingly. But I did not interfere with their techniques, which are quite visible on the work as the three panels look quite different in terms of techniques. Since they work for me full time, they have a monthly salary which is 90% higher than the minimum wage.

Two of the women work for me. Orn is an assistant in the studio and she is of Mon ethnic background, Ing is a housekeeper and comes from Payao, which is in northern Thailand close to the Burmese borders. The other lady is Karenni and works as a housekeeper for the photographer I’ve collaborated with. The only man in the photographs was cast from a several Burmese men that work at the market.

One detail image of the cloth shows their plight and the beginning of their journey (religious discrimination) while the other image shows their destination, where, in this case, they end up working in a fishing industry.

Through this process, my Thai assistants were able to learn something about our neighboring country and its problems. Mind you, all of them have very limited education, so refugee problems and history obviously are not on their mind. By embroidering these violent images, they were able to learn a thing or two while engaging in a dialogue with my Burmese (Mon) assistant. I had to bring up these issues, of course, in order to start a conversation otherwise they wouldn’t have asked. This is due to our poor educational system. People just simply don’t question things.

I did not specifically ask my Mon assistant about her personal experience. I know for the fact that she’s not fond of the Burmese government. She refuses to be called a Burmese or a person from Myanmar.

Most people identified with the problems the Rohingyas face because it’s been constantly in the news for the past couple of years. Other than that, most Thais are not aware much about the history of our neighboring countries. They know that the Burmese sacked our old capital, Ayuthaya, a few times and that present day Burmese are working as domestic workers in Thailand. There is always been this animosity towards the Burmese because of the one sided history we learned from school. When Thais travel to Burma, they are referred as Yodhya.

This is the reason why I raised this issue with this particular series. We are so near and yet we know nothing about each other.

Author

Jakkai Siributr’s art is internationally-recognised and has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions in Asia, Europe and the United States. In Thailand, his work has been shown at The Art Centre, Chulalongkorn University, among others. Jakkai’s pieces are featured in numerous institutional collections, including the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; the Vehbi Koç Foundation, Istanbul; the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art.

Jakkai Siributr’s art is internationally-recognised and has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions in Asia, Europe and the United States. In Thailand, his work has been shown at The Art Centre, Chulalongkorn University, among others. Jakkai’s pieces are featured in numerous institutional collections, including the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; the Vehbi Koç Foundation, Istanbul; the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art.