- Ramesh Mundal’s House, year unknown, mud, stone and wood, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal, Weaving at his Loom, 2020, Cotton And Synthetic Threads, 2×6 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal, Pick and Loom, 2020, Cotton And Synthetic Threads, 2×6 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal and son Shyam, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal, Durry 2, Year unknown, Cotton, 2×3 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Mural in House, Year unknown, Mud and white paint, Photo Kaamya Sharma

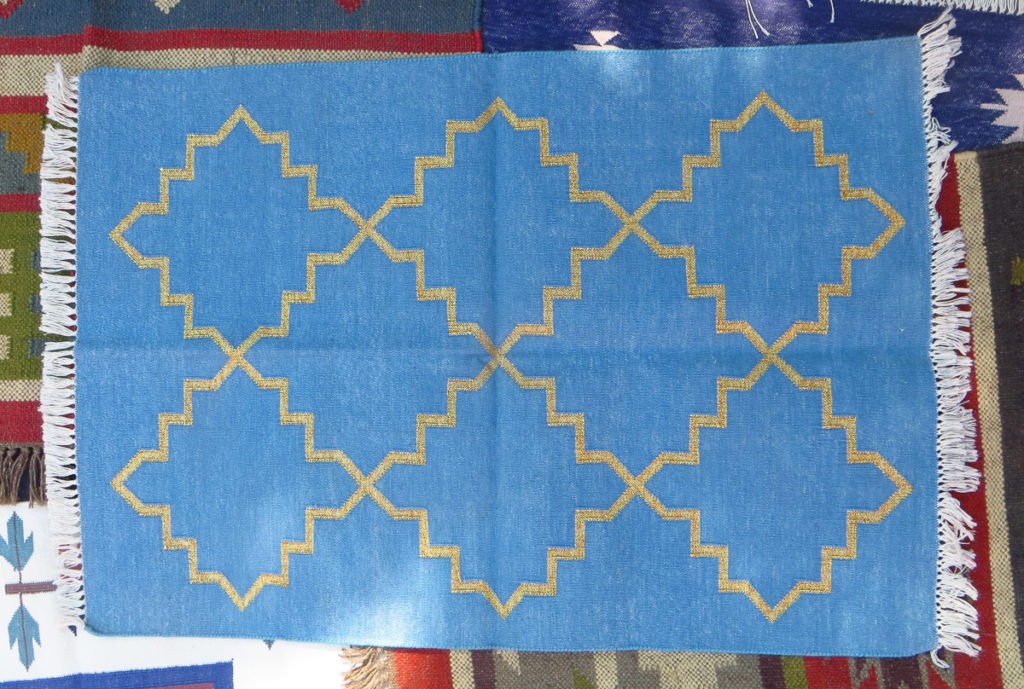

- Ramesh Mundal, Durry 4, Year unknown, Cotton, 2×3 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Durry Storage Room, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal, Durry 4 close-up, Year unknown, Cotton, 2×3 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal, Durry 5, Year unknown, Camel Wool, 4×6 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

- Ramesh Mundal, Durry 7 (Close-up), Year unknown, camel wool, 4×6 ft, Photo Kaamya Sharma

New to Rajasthan, Kaamya Sharma takes a road trip to find Ramesh Mundal, a renowned durry weaver, and looks behind the scenes at his presentations for tourists.

(A message to the reader.)

When I met Ramesh Mundal for the first time, I was struck by how easy he was in his own skin, perhaps the result of working at home. Half an hour into our conversation, he stretched into a reclining position on his cot. He did not shy away from sitting close to me while he explained how he worked his loom to make durries—rugs resilient enough to last fifty years of rough use. I was new to Rajasthan, barely seven months into my transition from life in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. I had learned in this brief time that my upper-caste surname granted me respect and access. My being a woman sometimes inhibited it. In Chennai, the heart of the Madras Presidency, the phantasm of British colonisation is part of your material and extra-material realities, in the architecture of buildings, the names of roads, and people’s valorisation of bureaucracies. Jodhpur, with its feudal codes and indifference to government, felt like it had never known a reality other than that of a princely state. As a recently inducted servant of a government bureaucracy (the Indian Institute of Technology), I felt this indifference acutely whenever I went out.

Salawas, the village where Ramesh lives, is off the shiny National Highway 62 just outside Jodhpur. “What is this yellow-flowered crop I see fields and fields of?”, I ask Mahipal, my taxi driver, as we make our way there. “Rayda”, he replies, which he is then obliged to repeat a couple of times until I catch its distinct Marwari sound. “Like Sarson (mustard)”, he elaborates, “people use it to make edible oil”. I notice that Salawas also has another kind of oil, large tankers ferrying fuel back and forth from glossy depots owned by Hindustan Petroleum and Indian Oil. After a level crossing, a busy intersection and narrowing roads, we reach our destination. Ramesh Mundal Durry Udyog (Ramesh Mundal Durry Company), the board announces in bold English letters, in contrast to the Devanagari signage that dominates much of even urban Rajasthan. Ramesh and his wife Rani are just inside the gate to his house, an open compound fashioned out of stone and mud where two round huts sit with thatched roofs. A large loom lies in an adjoining compound, smaller looms are scattered here and there, and there is plenty of space to park one’s car. The mud walls of the compound are marked by murals in white paint—Ramesh says his sister did them. One of these figures is that of a hatted man smoking a pipe and gazing at a hookah. I wonder if this is what Ramesh’s sister imagines a firang (foreigner) is like. There are no plastic chairs to be seen; instead, there are two wrought iron chairs with white and terracotta-red ropes diagonally woven to form the seat. I discover that Ramesh wove them himself. The house could be a template for rustic chic, every material choice reinforcing this impression.

Ramesh talks in Hindi as he weaves, using his heavy pick with the wooden handle and iron spokes to push the threads of the weft under and over the warp. As I focus on what he is saying, the pattern on the loom slowly materializes, in the form of a neat, discernible shape such as a hexagon or circle, the eye of an animal or bird. This kind of work looks so repetitive and almost monotonous in action that it is easy to forget that there is design and deliberation behind it.

“My great-grandfather began this work; he moved to Salawas from Khetasar and set up his looms here”, he says. When I ask him about the origins of durry weaving, he tells me it must be at least a hundred years old. “These durries just happened to be made in Salawas. But today, they are sold because of the Salawas name”, Ramesh says, hinting that authenticity acquired through provenance is often accidental. Eager to help, I try to tell him about the usefulness of obtaining a GI (Geographical Indication) tag. He refers to it as a “logo” from that point onwards.

In Ramesh’s telling, durries evolved out of farming ropes made from goat wool and boras (bags) slung on camel backs to carry things. The first durries were primarily white, black, or brown—the colours goats came in. People in the village drew inspiration from what they saw and asked for a horse, peacock, or elephant design; sometimes they wanted the village flag on the durry. The first designs were born as a result. Ramesh also tells me about a durry variant called the ganda, a plain rug commissioned by the Rabaris (nomadic, camel-herders) that members of his caste (the Prajapatis) would weave, an essential part of a girl’s dowry. The ganda would go with her and remain an ever-useful part of the household, resilient to mud and dust (“Only its name is gandi” (dirty)).

As we continue talking, Ramesh and Rani unfurl the durries that are stashed away in a third, small room. They range in all sizes, from being able to accommodate just one person to a modestly sized Indian joint family. The colours zigzag in and out of the patterns, yet the overall effect is one of startling, geometric clarity. Some of the durries come in muted, earth tones (the kind that would meet the approval of the Arts and Crafts overlords, once described disparagingly to me as the “mud brigade”) while yet others reflect a bright, chemically synthesized palate. I bring up a durry commissioned for a friend of mine which is an exact replica of a Bauhaus painting. I ask Ramesh if he knows that he has faithfully rendered the artistry of a German design movement. He shrugs in response, “we get many customers from France and Germany”.

At this point, he is called away to attend to tourists they have taken on a “desert safari”. Rani waits for the phone call which will dictate her next move and it eventually comes. The tourists want dal bati churma (roasted dough balls in lentil curry) for lunch. She sets about preparing the chulha (mud stove), first fetching a pile of dry wood and dung. When I notice the gas stove in their kitchen and ask her why she wasn’t using that instead, she shrugs and says, “some people prefer this”. Soon, the compound is filled with the dense, discomfiting fumes of burning wood.

I wonder at this couple that has so adroitly figured out how to present themselves for a “discerning” audience. There is a history of craftspeople being viewed as traditional, authentic, non-modern, anachronistic that goes at least as far back as nineteenth-century Britain. Perhaps, they have internalised the rules of the game and learned to play it better than anyone. An anthropologist is always thinking of ways to render people authentically in description. Ramesh and Rani render themselves seamlessly as craftspeople, holding up a mirror to our quests for authenticity.

Further Reading

Chatterjee A (2015) India’s handloom challenge: Anatomy of a crisis. Economic and Political Weekly 32: 34–38.

Government of India (1985) The Handlooms (Reservation of Articles for Production) Act. (accessed 20 January 2019).

Greenhalgh P (1997) The history of craft. In Dormer P (ed.) The Culture of Craft. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 20–51.

Liebl M and Roy T (2003) Handmade in India: Preliminary analysis of crafts producers and crafts production. Economic and Political Weekly 38(51/52): 5366–5376.

McGowan A (2009) Crafting the Nation in Colonial India. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mohsini M (2011) Crafts, artisans and the nation-state in India. In: Clark-Deces I (ed.) Blackwell Companion to the Anthropology of India. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 186–201.

Vaidyanathan G (2018) The fruitless quest to save Indian women from slowly choking to death. Quartz.com, 14 December. Accessed 1 February, 2020.

Venkatesan S (2009) Craft Matters: Artisans, Development and the Indian Nation. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Pvt. Ltd.

Wilkinson-Weber C and DeNicola A (2016) Critical Craft: Technology, Globalization, and Capitalism. New Delhi: Bloomsbury.

Author

Kaamya Sharma is Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur (India). Her academic and extracurricular interests revolve around material culture, craft, clothing, and popular culture. Presently, she is working on a project that will use computational tools to augment craft-based production and consumption in and around Jodhpur, Rajasthan. More details can be found at: kaamyasharma.net.

Kaamya Sharma is Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur (India). Her academic and extracurricular interests revolve around material culture, craft, clothing, and popular culture. Presently, she is working on a project that will use computational tools to augment craft-based production and consumption in and around Jodhpur, Rajasthan. More details can be found at: kaamyasharma.net.

Comments

Sharwan mo.9929110870

xyp1wv