- Visitors playing the social lamellaphone at SNO Contemporary Art Projects, Marrickville Sydney NSW 2014, photo: Gary Warner

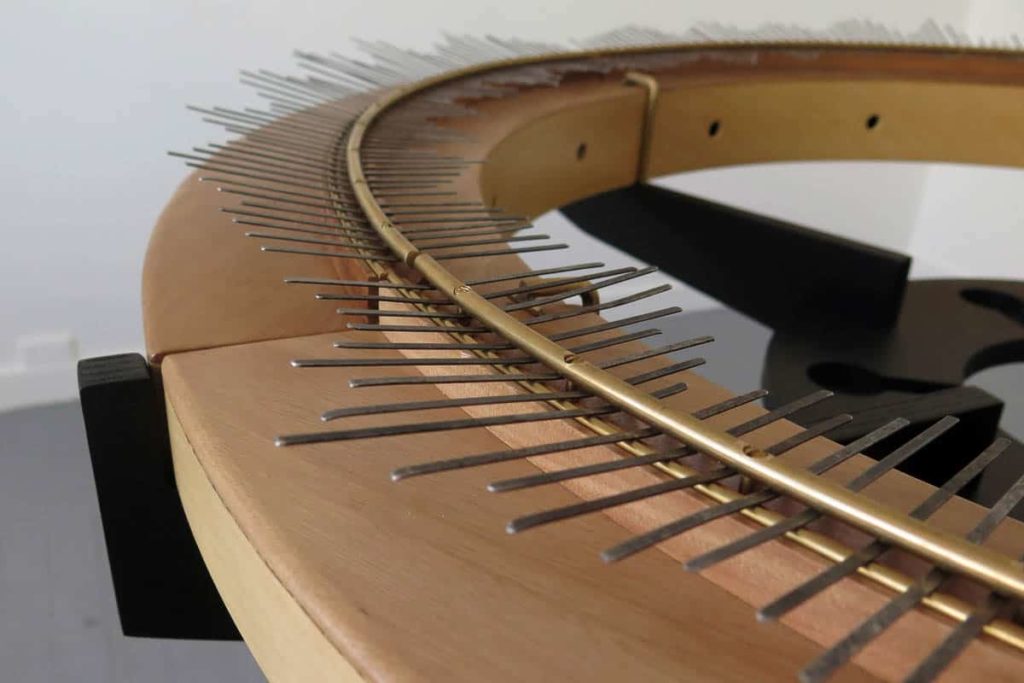

- The social lamellaphone [detail], photo: Gary Warner

- Visitors playing the social lamellaphone at SNO Contemporary Art Projects, Marrickville Sydney NSW, 2014, photo: Gary Warner

- Visitors playing the social lamellaphone at Somersby as part of the One Month Festival, 2016, photo: Gary Urquhart (video still)

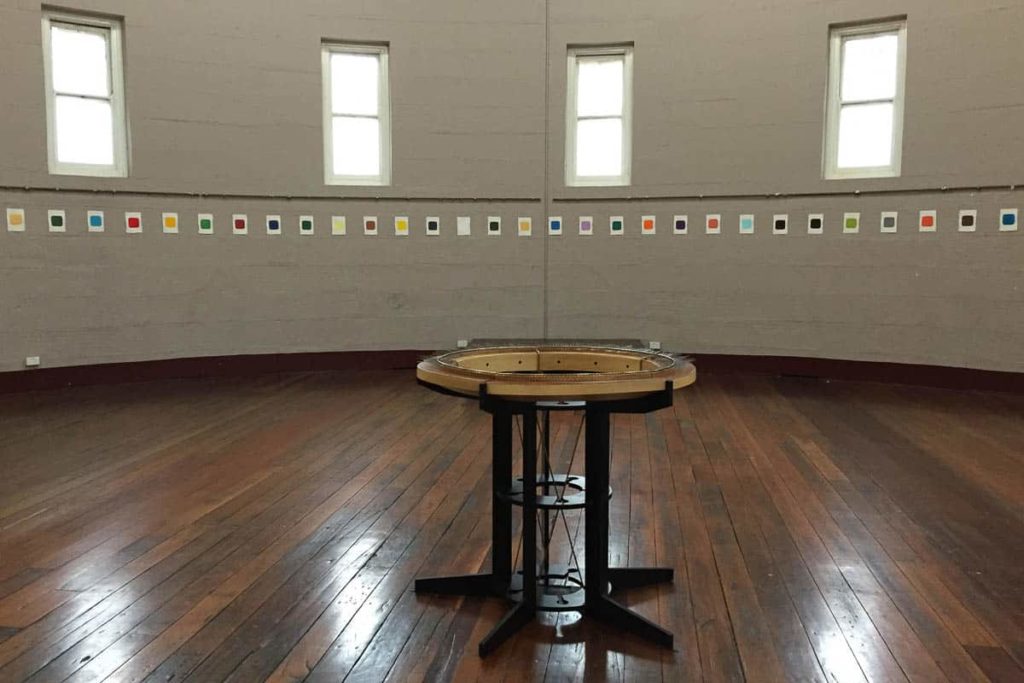

- The social lamellaphone and colournotes at SNO Contemporary Art Projects, Marrickville Sydney NSW, 2014, photo: Gary Warner

- The social lamellaphone and colournotes at the National Art School, Darlinghurst Sydney NSW, 2015, photo: Gary Warner

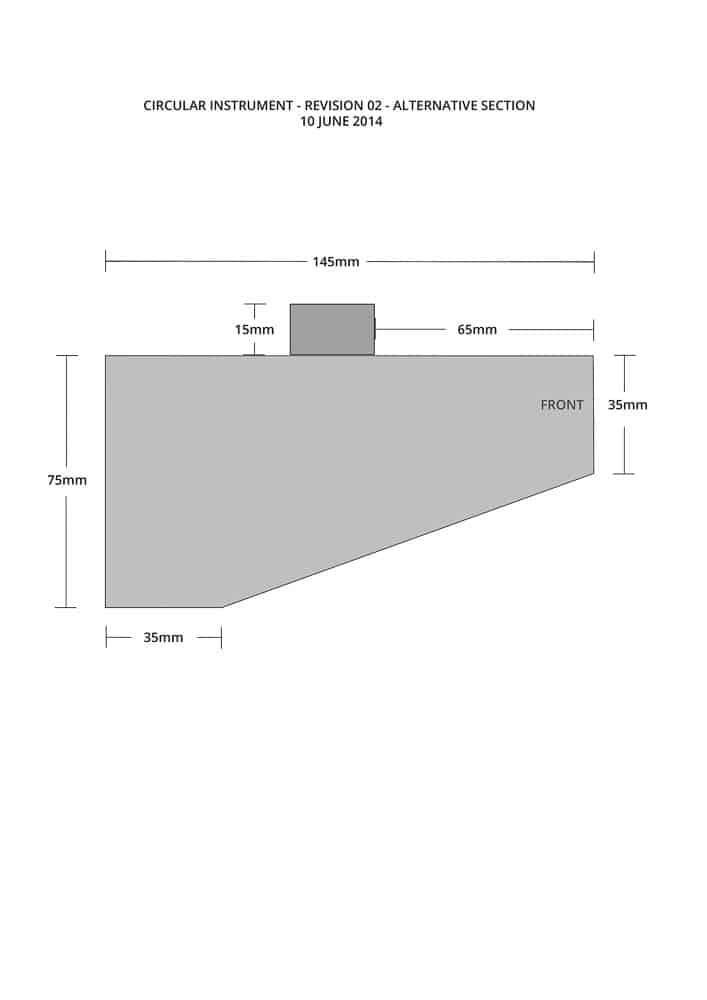

- Gary Warner, dimensioned construction sketch for the social lamellaphone, 2014

The social lamellophone is a unique acoustic instrument and sonic sculpture designed and constructed for experimental music making and the social exploration of cooperative creativity.

Mbira, sanza, likembe, kadongo, ilimba—all phonetic transliterations from diverse African languages of a few of the specific names for a typology of musical instruments, the lamellophones, popularly known as “thumb pianos” (a term disparaged as diminutive and inaccurate by some commentators). While not limited to Africa, lamellophone instruments are probably most prevalent and diverse there.

A lamellophone comprises a row, or rows, of long flat keys, reeds or tines (lamellae), fixed at one end, that are plucked using combinations of thumbs and fingers of one or both hands. Lamellae can be wood, bamboo or metal, but usually metal. While the pitch of notes is determined by length (longer = lower), the individuated timbre of each instrument results predominantly from a combination of type, thickness and width of the tine material. For example, Mbira typically have large, wide, thick tines made of heavy hand-beaten steel for a warm “thick” sound, while many other lamellophone types use thinner, narrower spring steel tines for a bright piercing sound. Other factors influencing the timbre are variations of substrate, resonator and attached rattles.

African lamellophone instruments are acoustic, intimate and portable, used in ancient traditional cultural practices and ceremonies as well as in contemporary entertainment, such as the extraordinary electrified likembe of the Congolese group Orchestre Tout Puissant Likembe Konono No. 1.

The constraining conformity of the Western chromatic scale is largely absent from traditional music cultures. African lamellophone instruments manifest a bewildering diversity of microtonal sequencing – some of which may strike the uninitiated listener as peculiarly discordant. Though there are definitive lineages of tuning, playing style and repertoire, there are also innumerable individual intuitive tunings, methods and expression arrived at through the imperatives of available materials, knowledge through making and the practice of playing. The African propensity for inventive upcycling of material discards is legendary – and lamellophone instruments are, today, typically handmade using found timbers and metal from containers, bicycle spokes, building nails, hubcaps and bottle caps.

I have long enjoyed improvised playing on a variety of hand-held lamellophones I’ve picked up at markets, mostly of the Kalimba variety which was devised and popularised in the late 1950’s by the British amateur music researcher and pioneering field recordist Hugh Tracey (1903-1977). Tracey deplored the detrimental effect evangelical missionaries were having on Africa’s traditional peoples and their musics, and spent decades travelling sub-Saharan Africa with his companion Babu Chipika, making audio recordings of traditional music, song and ceremony. He created the Kalimba (“little music”), tuned for the Western ear, in an attempt to broaden awareness of African musical tradition. The Kalimba now has a transcultural life of its own.

In 2002-03, while working on the Nyinkka Nyunyu Aboriginal Culture Centre in Tennant Creek I met Patrick McCloskey, who had then recently spent time in Zimbabwe learning how to properly play the Mbira instrument of the Shona people. He could really play, and on hot bright afternoons in the welcoming shaded interior of his rental flat, was gracious enough to help me learn a little about how to play and its cultural significance and centrality to Zimbabwean identity.

Patrick put me in touch with Mbira maker Sebastian Pott, a German man who lived in Ghana and learnt the craft with Zimbabwean master Chris Mhlanga. I bought a mail-order Mbira from Sebastian and love it’s warm deep resonant sound, its heavy-in-the-hands hardwood and steel materiality and made-to-last construction. But, of course, I’m not African and have no pretence to playing African music with this wonderful instrument. My pleasure with it is to simply improvise patterns, rhythms and melodic sequences that arise each time I sit down to play—evolving patterns and finger motions that forge an affective sonic expression for that fleeting moment.

An important sonic aspect of traditional lamellophones is a pulsing buzz or rattle effected by the vibratory shaking of small objects attached to the instrument or its sounding container. Traditionally, Mbira are held by tension, using a stick, inside a large open-faced hollowed calabash that serves as an amplifying chamber, and small objects are loosely attached around its perimeter. These objects were traditionally shells or seeds, but are more commonly now metal bottle caps, that vibrate in sympathetic rhythm with the plucking of the lamellae, creating a pulsing buzzing effect said to aid the listener’s immersion in the trance-like sonic field. In other lamellophone instruments, this buzzing is created by small rings of wire or hand-cut tin folded loosely around each tine on the opposite side of the bridge.

the project

Some ideas take root in the mind like a fig tree in a rocky crevice. Slowly they grow into an overshadowing presence demanding of attention. Such was my wondering for a few years about the notion of a circular lamellophone, large enough for a group of people to play together.

I had made a few small handheld instruments for friends and family using fish tins, brass rod and bits and pieces. Then I started to notice strips of spring steel littering the streets of Sydney as I walked on my many perambulations between studio, home and everyday life. Once noticed, they seemed to be everywhere, and for a long time I wasn’t sure what they were. Then early one morning I saw sparks flying from the swirling brushes of a council street-sweeper and realised the strips were snapped bristles.

Over a period of a few months, I collected over a thousand of these 3mm-wide flexible steel strips perfectly suited to lamellaphonic transmutation. I cut 300 lengths of 110mm, then hand-filed the ends to be rounded and blunt to the touch (when picked up from the streets, one end has been ground to a lethally sharp point, the other snapped to a rough skin-tearing serration.)

Philip Sticklen is a genius maker of things timber, brass, steel, concrete and glass. Trained in architecture but preferring hand-making, and inspired by Corbusier, Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, Phil has spent his life as an independent maker of furniture, fittings, houses, huts and unique joinery items for architects and artists (eg he built the monumental showcase installation for Fiona Hall’s 2015 Venice Biennale project). He was interested in the idea of making this unusual musical instrument and had some knowledge of Australian tone woods – the special timbers used in the making of classical wind and string instruments.

I needed the instrument to be “flat-packable”—I have a very small studio space, so storage is an issue, and wanted to be able to easily deliver the instrument by car or freight. Phil and I developed a neat modular approach to the instruments construction, comprising five similar units that fit together to create the circle. The stand is made of five identical uprights and three identical circular rings, the instrument is five curved sound boxes that sit on top of the stand.

At the time I brought Phil into this project, he had his workshop in a very large warehouse space—beside an industrial tip south of Sydney—shared with a variety of other trades and crafts people. One of these was Alex Rosemont who had recently bought a CNC milling machine. We settled on CNC milling the plywood stand and the obloid interiors of the instrument’s jelutong sound boxes.

Like a guitar or violin, the sound boxes are thin-walled and hollow, with a curvaceous interior profile to aid the resonant timbre of sound produced by plucking the tines. The top and bridge of each sound box is blackbutt hardwood—important to the instrument’s tonality.

The steel tines are held tight between two arcs of brass rod running the length of each sound box. One rod lies in a groove in the hardwood bridge; the other is set behind and has a series of holes for brass screws that press the rod down tightly on the row of steel tines. Loosening the screws allows tines to be pushed or pulled to length, tightening the screws fixes each tine in place, “holding” the desired note.

I did not want to impose an African tuning on the instrument and was more interested in some uncharacteristic variation of microtonal tuning. I initially researched length-frequency ratios for standard chromatic tuning, and tuned the instrument using a guitar tuner. But this resulted in a “sweet” conventional sound, too redolent of a music box. I then tried a structuralist approach by making each successive key 1mm longer or shorter than the previous but this resulted in a flat, uninteresting sound. Finally I decided to tune the instrument intuitively, starting with a single note, then tuning the adjacent note to an interesting accompaniment, and so on along the length of one soundbox. I then repeated this tuning (as close as possible by ear) on each of the other four soundboxes. It took three days to carefully tune all 270 tines.

Handheld lamellophones with a sound box always have at least one hole for the release of sound. This is usually on top of the instrument. In the social lamellophone I cut these holes in the internal perimeter wall of the sound boxes to project sound across the circle. Players can clearly hear the sounds they’re making, as well as the sounds being made by players on the other side of the circle.

I didn’t know if the instrument would work as a site of unrehearsed performative social engagement, which was a reason to build it, to find out. On the first outing, at SNO Contemporary Art Projects in Sydney, it was gratifying to watch and hear people happily plucking away making sounds together. More surprising was the eruption of animated conversations that coursed around and across the circle as people’s hands made sounds. With the hands busy, quasi-musical noise being made, and absolutely no imperative for mastery or virtuosity, people chatted, joked, socialised. Like doodling while sitting, talking on a landline telephone, the social lamellophone seems to create a syncretic all-brain left and right hemispheres space of mindflow that evokes senses of joy, abandonment and playfulness.

The social lamellophone is always accompanied by a series of small monochrome paintings, collectively titled colournotes, that line the walls, encircling the instrument like flowers in a garden. The paintings provide a minimal but effective alteration of the immediate spatial context, aiding a subconscious feeling of being uplifted. They are an intuitive set of colour tabs, inspired by an image of artist Eugene Carchesio’s studio that communicated to me a sense of joy, and evidence of the work of the artist in the making of abstract art. Also, these small paintings directly reference early modern and ongoing currents within abstract art exploring notions of colour-music, synaesthesia and cross-sensory evocation.

Finally, I’d like to make mention of John Cage… That should do it.

Author

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. He works on a wide variety of projects, across various media including sound, digital image, drawing, installation and performance, and contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and museum exhibitions. He recently curated ‘FIELDWORK: artist encounters’ at the Sydney College of the Arts. Current projects include the sonic-kinetic ‘aleatoric ensemble’, the ‘florachrome’ series deriving colour experiences from native flowers, and co-curation of a field recording exhibition in 2017. For more information, see garywarner.net.

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. He works on a wide variety of projects, across various media including sound, digital image, drawing, installation and performance, and contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and museum exhibitions. He recently curated ‘FIELDWORK: artist encounters’ at the Sydney College of the Arts. Current projects include the sonic-kinetic ‘aleatoric ensemble’, the ‘florachrome’ series deriving colour experiences from native flowers, and co-curation of a field recording exhibition in 2017. For more information, see garywarner.net.

Comments

Very nice indeed – but some audio or video wouldn’t go astray.

Good point Mark. Try this again.