- Example of a Flower and Water Bowl, Ubud, 2013, Photo: Mary Lou Pavlovic

- Canang Sari, Nyuh Kuning, Bali, photo: Mary Lou Pavlovic, 2018

- Water Feature with Flora and Fauna and Ganesha Nyuh Kuning, Bali, Photograph: Mary Lou Pavlovic 2018.

Water: the first time I visit the island of Bali, Indonesia in 2008—Ubud, to be more precise—I am dazzled by its beauty and abundance of lush, tropical green foliage, rice fields, and mostly, water. Droplets on cool frangipani leaves. I see thick brown water in beautiful lotus ponds. Water trickling through small canals or along streams at the sides of roads throughout Ubud, which is the artistic centre of Bali. Water, pooling serenely inside water palaces and temples. Water flooding rice fields, sparkling in the sun; water, surrounding the island—in which I enjoy lazy days snorkelling, just hovering over the magical, tropical sea-life.

Flowers: firstly, I notice the Ubud lotus ponds: giant pink and white lotus, with olive green, velvety leaf pads spread out over the surfaces of the brownish pools. But then I see that pretty flowers are also used by Balinese Hindu women in small, identical offerings (canang sari) to the gods and placed all over the streets of Ubud daily. Signage at the Monkey Forest, Ubud, reveals that water and flowers are sacred in Balinese Hinduism, (Agama Hindu Dharma) the religion practised predominantly on the island. I see that flowers and water are featured in abundance in the ornate, intricate and sometimes fragile architectural structures and landscape architecture in Bali, that, like much of the traditional Balinese Hindu arts, are concerned with creating beauty and dedicated to the gods. I am also drawn to architecture and architectural fixtures referring to flowers and water.

In the 1930s the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, visiting Bali, described the ornateness of Balinese arts, saying that “they (the Balinese) admire technique and good craftsmanship above other points … Balinese art is a highly developed, although informal Baroque folk-art.” I am interested in Covarrubias’ term “informal Baroque” to describe Balinese art forms. The term Baroque relates to the characteristics of a Western artistic style prevalent in the seventeenth century. Baroque engages complex forms and bold ornamentation, often conveying a sense of movement. I think that Covarrubias’ term “Informal Baroque” relates to the manner in which the Balinese often engage ephemeral, economical materials such as coconut leaf, as opposed to expensive materials, for example, marble or gold in their artistic production. Coconut leaf, for example, is engaged with dramatic ornamentation to create religious offerings.

In a 2012 interview with Balinese curator, Nyoman Muka, at the Museum Rudana in Peliatan village, Bali, I ask about the ornateness of Balinese arts. Muka says that the intricate, ornate quality of many Balinese art forms is an expression of one of the three basic human qualities important in Hindu cosmology: patience (the others are ignorance and goodness.) Patience must be practised, for example, in the complex carving or the minute details of traditional Balinese painting. Muka says that in Balinese Hinduism, visual beauty, an important aspiration of traditional visual art and design, is realised often referring to nature, or with natural materials and excellent crafting. Ornate design in a traditional artwork invites a momentary, pleasurable, sensory response from viewers. Muka says Balinese Hinduism teaches that the subject’s fleeting experience of visual beauty in creative art forms reminds us that life is transitory and afterwards comes death. The Baroque is a moving quality in many Balinese art forms that reflects a sense of “aliveness” that heightens this experience. From what I can determine, Muka thinks that some of the traditional Balinese arts engage a vernacular of beauty—flowers and ornamentation—hoping that others will find these beautiful too in order to experience aspects of the Balinese Hindu teachings.

During several trips to Ubud from 2008–2014, a sense of the informal Baroque catches my eye in floral water bowls, found all over the streets. Flowers are arranged abundantly and informally, but with a sense of ornate, decorative design, and suspended in large ceramic bowls of water. The decorating of these Balinese flower bowls is more or less a profane practice outside many shops and hotels. I think that the effect is spectacularly beautiful and complex, and because of this, I am drawn to closely examine these flower and water arrangements. The floral water bowls of Ubud give rise to the sculptural body of studio research created for my PhD. A whole trajectory of sculptural forms, derived from the simple idea of placing flowers to float in water has been created for my studio research, that also identifies with the ephemeral nature of life in Balinese culture, but my practice is executed in more permanent forms.

An example of my studio production is Sample Stick from the Garden of Atlantis, 2011, in which artificial flowers and resin emulate real flowers and water. I do not believe that my studio research relates primarily to a sense of the Baroque. There is no dramatic ornamentation: the aesthetic dimension involved suspended flowers in clear liquid. I do this principally because I find the effect beautiful. I am aware, however, that the issue of life and death in my practice might become relevant later in my research. Flowers are also signs for beauty in Western art history, philosophy and also in an every-day sense. Suspended flowers, abundantly displayed in Bali, are arranged in my practice in classical Western sculptural forms that engage the vernacular of contemporary art that is grounded in Western conventions in the form of mixed media, plastic, lights and decorated sculptural plinths.

- Mary Lou Pavlovic, Rosebud, 2011, 70 x 40 x 40cm, Mixed Media

- Mary Lou Pavlovic, Bali on a Blue Day, 2011, 75 x 50 x 90cm, Mixed Media

Other fragile elements of the Ubud public environment are incorporated into my studio research. I see black and white checked fabrics adorning shrines and temples, wrapped around trees, and worn as sarongs on members of the village security (pecalang). Eventually, this checked pattern is painted onto the supporting structures for two of my cast resin studio works, Rosebud, 2011, and Bali on a Blue Day, 2011. These are sculptural works that juxtapose a black, grey and white hard-edged grid with the organic shapes of flowers floating in water-like resin.

The checked pattern juxtaposed with organic forms provides a strong aesthetic contrast in my studio works that I think increases their aesthetic complexity. A painted, decorated, checked base is also an aesthetic solution for a support structure needed for these studio works to save them from what I think is a more visually mundane solution, a conventional white plinth. Painted checks draw attention to the sculptural support and incorporate it into the studio work lending the practice a postmodern idiom that deconstructs the idea that a traditional white plinth neutrally supports sculpture. Therefore the studio work becomes part of critical contemporary sculptural dialogue about sculptural objects but remains tied to traditional aesthetic discourses. The check pattern is a loaded form. I see it in a Balinese Hindu context, Western textiles and sport, for example, racing car flags and in art as modernist grid. I think that, however, my use of this ubiquitous form in combinations of check and floral resin and the title of the work, Bali on a Blue Day, also link the practice to Bali, more so for viewers that are familiar with Bali.

In Bali, the checked textile (kain poleng) is the most sacred Balinese Hindu textile. The kain poleng symbolises good, (white) bad (black) and the grey formed by overlapping thread from the black and white represents the mix of good and bad, symbolising the balance of the two opposing forces. Kain poleng is placed anywhere that Balinese Hindus believe has the potential to have negative niskala (otherworldly) forces. Balinese Hindus use fabric for protection against the forces of negative niskala; complex patterns and motifs historically form a language of protection.

After I finish making Rosebud, 2011 and Bali on a Blue Day, 2011, I ask the Balinese Hindu painter, Pak Bendi Yudha, who also has a research interest in Hinduism, if it is considered offensive to Balinese Hindus for a non-Balinese Hindu to make images relating to the kain poleng. As combinations of check and floral offerings are familiar to visitors of Bali who may also encounter my studio work, thereby making a connection to Bali. Also, a broader audience is provided with a reference to Bali in the titling of my studio work. Pak Bendi assures me that it is not offensive for non-Balinese Hindus to reference the kain poleng; he is aware that checked fabrics are part of other cultures and carry other readings. Yudha also says that Balinese Hindus consider that if religious symbols are not denigrated, then they are only celebrated in sharing them.

I think that it is the uniformity and repeated utilisation of flowers, water and textiles in Balinese Hindu religious and creative activities, dominant in the public environment, which causes me be drawn to them as visual, sensory magnets in the first place. This repetition gives rise to the creation of my above-mentioned studio works. Uniformity and repetition of flowers, water and checked textiles that I encounter throughout Bali are strong reasons for their impact on my practice. The Russian Southeast Asian academic, Vladimir Braginsky, suggests that repetition in the arts of Eastern cultures historically often captures the attention of Western artists, enabling Western artists to draw on what they need for their own cultural development.

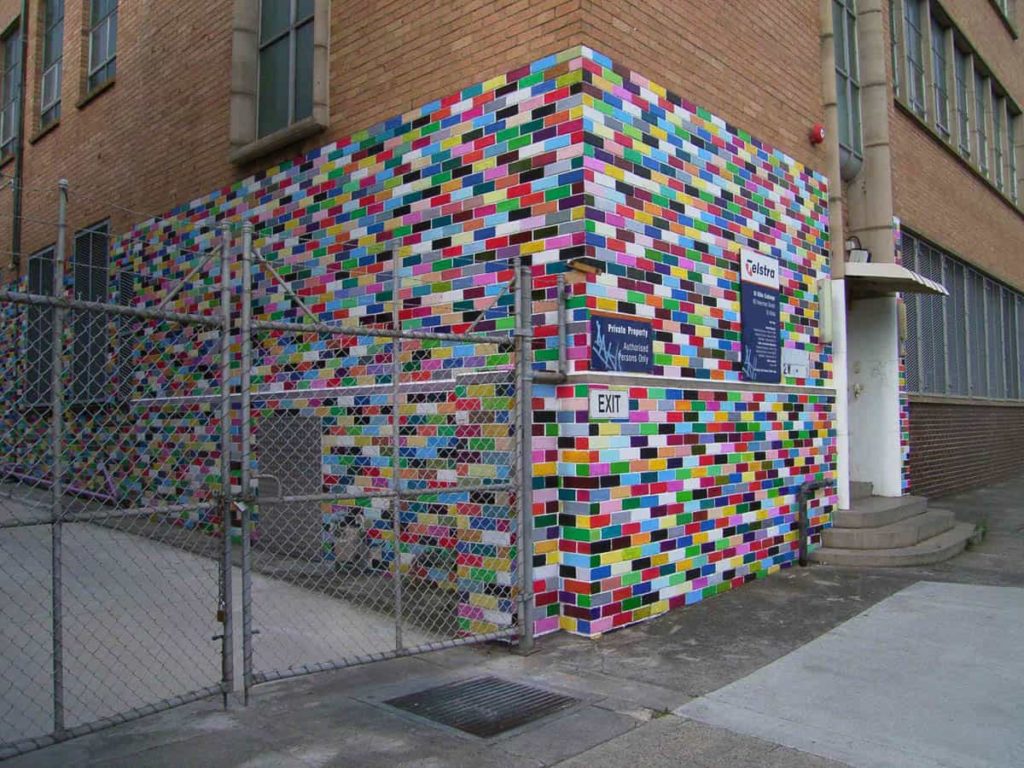

Another studio work, The Outsider, a public artwork painted around the Telstra exchange in St. Kilda, Melbourne, is partially indebted to the Balinese Hindu practice of wrapping colourful textiles around architectural structures in the built environment. I see the painted surface in The Outsider as a type of fragile skin around the Telstra exchange. That I am partially influenced in The Outsider by shrines draped with textiles in Bali may not be an immediately recognisable aspect of this public artwork. Overall, viewers of all my research works who have visited Bali may appreciate the Balinese references. I believe that ultimately, however, these studio works begun early in my research remain engage with their own more traditionally Western dialogue, in that they reference Bali in varying degrees, but engage the broad language of contemporary art grounded in Western conventions.

- Mary Lou Pavlovic with Ketut Suaka, Flora and Patra, 2015, Dimensions variable, Mixed Media

- Mary Lou Pavlovic with Ketut Suaka, Flora and Patra, 2015, Dimensions variable, Mixed Media, (C) Mary Lou Pavlovic Monash – MADA Gallery

Working in a creative research environment at ISI Denpasar with Balinese artistic practitioners, however, quickly influences my studio research. I create a group of long, thin poles, made with artificial flowers and resin. The flowers in the poles are much brighter than in previous studio research. I am searching for methods in which to visually link my resin studio works to the brightness of the coloured brick work in The Outsider project, in order for the final exhibition/examination to be aesthetically cohesive. In my subjective aesthetic judgement, I believe that a sense of aesthetic cohesion will contribute to the exhibition’s beauty. A support structure for each pole in order for them to be able to stand is required. Pak Bendi Yudha, a senior lecturer at ISI, suggests that I work with a Balinese traditional woodcarver who will create a stand, incorporating traditional Balinese Hindu design patterns. Pak Bendi thinks that, by doing so, a collaborative Balinese/Australian studio work will illustrate the Hindu principle of lingga-yoni (union of opposing forces) that is often seen in Hindu sculpture as a vertical element joined with a more horizontal element.

At first I am reticent, I am concerned again about the ethics of appropriating another culture’s imagery. The Balinese Hindu traditional patterns, incorporating floral designs are also culturally specific. Pak Bendi’s Balinese Hindu reading of a collaborative art project combining my pole works and Balinese carved patterns is one thing, but how will my studio work be read in Melbourne? Will my practice be regarded as Orientalist, in that I am seen to construct images of an Eastern culture that serve the West in maintaining domination over the East? Am I just helping myself to whatever cultural items that I like, arrogantly disregarding their significance and importance to others? But then, my Balinese colleagues are so enthusiastic and supportive of an artistic collaboration, and so I decide to explore this question of cultural appropriation in my practice. I am concerned that not working collaboratively with Balinese artists, because we are from different cultures, is potentially a dangerous idea that promotes cultural segregation. I am against cultural segregation.

I think of the Australian artist, Tim Johnson, who embraces spiritual iconography in Indigenous and Eastern cultures. Johnson invites friends from different cultures to contribute to his paintings, imbuing them with spiritual icons. An example is the collaborative installation, Yab Yum, 2001, in which Johnson paints his imagery and Vietnamese artist My Le Thi paints Buddhist images of the Buddha Shakyamuni in meditation. Like Johnson, I am open to my practice charting human relations across cultural divisions especially when there is a shared interest in the subject of beauty. Traditional Balinese Hindu carving practice often utilises flowers and is concerned with creating beauty, for sharing and for the hope of conveying positive experiences of Hinduism. Although this idea may be quickly countered by saying that beauty is subjective for everyone, and not all people find the same things beautiful, I am interested to experiment with one to whom beauty is important, and who, like me, utilises a conventional sign for beauty, the flower, in order to begin to draw some conclusions about the subject of beauty in the studio research. I also believe that in collaborative practice, there has to be an element of risk undertaken, that is, not knowing what the outcomes will be, in order to make any advances in studio production.

In the spirit of experimentation, I collaborate with Balinese traditional woodcarver Ketut Suaka to create stands for the pole studio works. Suaka carves the bases, adorning them with the traditional Balinese Hindu patra, (patterns.) These are ornate, official Balinese Hindu patterns used in textiles and wood and stone carving that adorn Balinese Hindu buildings and various Balinese objects. The patra are largely comprised of flowers and leaves—stylised versions of the lotus, a major Hindu religious symbol. Suaka combines patra sari, patra cina, patra olanda, and ornamentation motifs, bungan tuwung and mas-masan, stylising these as he sees fit. As we work together our ideas develop, and we also complete a series of wall hanging poles, in which Suaka and I join our respective practices. Suaka responds to my floral resin poles, creating and stylising the types of traditional patterns in Balinese Hindu design that he deems aesthetically appropriate for my studio work. The resulting studio production for two studio works in the final exhibition/examination is overtly cross-cultural. Western art forms influenced by the aesthetics of Bali are fused with Balinese Hindu religious design, in which beauty is an important ideal.

Overall, the studio works referencing flowers draw largely on Western and Balinese symbols of beauty. The methodology engaged to create the studio works in the PhD practice are derived from Suaka’s and my subjective perceptions of beauty. Our aesthetic ideas incorporate flowers and refer to nature and patterns. I argue that because the final studio works reference readily recognisable symbols of beauty that I am then able to consider beauty’s agency operating in the practice and subsequently assign a theory of beauty’s provocative capacity in the field of contemporary art grounded in Western conventions.

I acknowledge that there are issues in my practice, for example, intercultural relations, that fall outside my research project’s primary focus: the provocative capacity of beauty. My exegesis is not intended as an encompassing narrative for the practice—rather, I have chosen to focus on one question of importance in aesthetic discussion today. Yet in advancing the studio research I am open to exploring new avenues of practice that are in keeping with my interest in the subject of beauty. What can invoking beauty in art do today?

Orientalism or synthesis

The allure of Bali for my studio research, however, opens up a question. What general considerations, might be addressed for a Western artist working in the domain of the East-West cultural interface, in the era of globalisation? In the past, much attention has been given in Western academia regarding Western artists appropriating Asian motifs, images and practices. The Russian Southeast Asian studies academic, Vladimir Braginsky, draws attention to the recent dominant impact in Asian studies of the Palestinian American scholar Edward Said’s (1935–2003) theories of orientalism expressed (although not specifically on Southeast Asia) in his 1978 book of the same name. Said’s theory of orientalism analyses its discourse, in which (predominantly) French and British scholars, writers and artists of the colonial period, in their pursuit of knowledge about the East (primarily Arab-Islamic), consciously and unconsciously serve the colonial powers of the West in maintaining superiority over the East, by distorting images of it, rather than recognising images of reality.

In his review of two books emerging from a 1991 conference on East-West cultural relations on the themes of Europe and the Orient at the Australian National University, Canberra, Braginsky refers to the editors’ argument that it is the task of scholars today in the entire Asian studies profession to problematise and to question every dimension of that orientalist division. I would like to explore this idea in my own research project referencing Bali. Surely one way (albeit narrow) to read the studio works referencing the kain poleng and flowers may be seen as literally distorted image of Balinese culture. Flowers are often located where the kain poleng is placed around shrines, and my practice responds to this idea. Additionally, is there an alternative to an orientalist model of practice for Suaka and my collaborative studio work?

In terms of Western artists and scholars engaging with the East, Braginksy, whilst acknowledging Said’s humane and ethical pathos, (as do I) argues against some of his ideas. Fundamentally, Braginsky argues that it is well known that long before orientalism, as early as the 1920s and 1930s in social sciences, scholars are acknowledging that the researcher herself inevitably causes distortions of truth. This is because the researcher’s mentality is determined by culture, and can only be the sum total of semiotic systems of the given society; all research is always only an image or model of truth. Braginsky rightly asks why Said argues that this distortion of truth is specific to colonialism, and not of anybody encountering another culture. My research project is no different—no claims are made in my research for presenting unmediated truths.

Whilst power relations are important considerations between cultures, Braginsky argues that they are far from the sole or immediate determinant of the artist or scholar’s thoughts. He also argues that there is a basic difference between scholar and artist. Scholars studying the East are concerned with how to present it properly, whereas Braginsky says that the only job of the artist, at home or abroad is to create. Through immediate, intimately personal works artists are solving the problems of their own cultures at any given time. I agree with Braginsky in terms of power relations. In my mind, I am certainly thinking of more than power relations when encountering the artists and cultures of Bali. For example, I consciously think in terms of empathy—by researching Balinese society— ethics, formal techniques, visual and conceptual similarities and differences. I think of the knowledge that I can share with Balinese practitioners interested in my practice. And homage: how much further ahead in creating the beautiful aesthetic arrangements incorporating flowers, water and geometric textiles that I refer to in my own practice, are the Balinese.

I view the processes in my studio research as a type of synthesis with specific elements of Balinese culture, such as checked textiles, aqueous floral arrangements and traditional, patterned woodcarving. Suaka’s contribution, floral carving, retains its Balinese identity. I do not suggest that he alters his practice or participate in a project in conflict with his religious beliefs. There is Balinese agency in our studio research. In my experience as a visiting lecturer at ISI Denpasar, I am invited to share skills and knowledge about my Western practice in a contemporary Balinese artistic environment that draws on Western art, Eastern art, and largely Balinese traditions and contemporary Indonesian art. Additionally, I draw attention to how much the Balinese themselves appropriate from other cultures what they need for their culture. The Balinese barong, the good spirit commonly imaged as half-lion, half-Pekinese dog, relates to the Chinese dragon, and Balinese painting adopts European elements into some traditional painting that today has many forms.

From my perspective, my research is not designed to contribute to discussions of Balinese culture proper, it is designed to further my own practice in terms of my own Western culture and recognise my own practices’ capacity to respect and engage with other cultures to extend knowledge. I disagree with Braginsky, however, that to create is the only job of the artist. I believe that in critical practice, the job of the artist is to create and to use one’s brains to think about what has been created.

All this, however, leads to two more points made by Braginsky. He discusses the scholarship in the books that he is reviewing, regarding the valuable place that the East represents to Western artists. He refers, amongst others, to the importance the Indonesian gamelan provides for French composer Claude Debussy, (1862–1918), Japanese painting provides for French painter Claude Monet, (1840–1926), Chinese drama for German playwright Bertolt Brecht, (1898–1956), Javanese architecture for Dutch architects Maclaine Pont (1884–1971) and Thomas Karsten (1884–1945), and to the European avant-garde artists in the first half of last century who are searching for ways to express anti-traditionalism. To many significant Western artists, the East represents a place where what the artists are looking for has already started in their own culture and is exaggerated in the East. Braginsky says that “sometimes Western artists found in cultures of the East a repository of the creative decisions they were looking for, sometimes a resonator of sorts, amplifying the ‘loudness’ of decisions almost made, and sometimes a confirmation that the decisions were made rightly.”

I identify wholeheartedly with Braginsky’s comments. I had already begun to use flowers in my practice before my first visit to Bali. For example, The PavModern Art Plinth, 2007, comprises a rose joined to a rat’s body, suspended in a geometric resin block. In 2007, my intention is to develop this studio research in terms of beauty. The flowers remain, as these are obvious referents to beauty, but I dispense with what I think are ugly elements, for example, the rat. In creating objects inspired by my subjective ideals of beauty seen in Bali, I am able to construct my own largely Western studio production that acts, by virtue of its referents to beauty in Western art history, philosophy, and every day life (flowers, nature) as a catalyst for discussion about Western notions of the provocative nature of beauty.

Another point that Braginsky makes is that Western artists engaging with the East are criticised for not being more erudite, engaging superficially with the Eastern cultures from which they draw inspiration. Although he does not clarify where this is located in the books that he reviews.

In my research I have discovered the Surrealist playwright Antonin Artaud, (1896–1948), who is so inspired by the perfection of Balinese dance that he draws on it to create a radical work in his own culture. Artaud’s 1938 book, The Theatre and Its Double, is widely regarded as changing the course of Western theatre, and the foundation of modernist theatre. Occidental theatre, in Artaud’s time, is based on linear narratives. Knowing little of Balinese dance, Artaud draws on its non-linear narratives and syncopations to argue instead that theatre and life are separate entities—hence the use of the word “double” in his book’s title. The Theatre and its Double expands permanently and politically the language of theatre in the West. Artaud solves theatrical problems in his Western context in a specific place and time, for example, how to make theatre more abstract and non-literal, by turning to Balinese culture.

I see my practice as drawing on aesthetic elements of Balinese culture to assist in resolving aesthetic problems in my own culture, namely how can artists invoke beauty and do so in a provocative manner? In today’s globalised art world, it is possible that these issues may be relevant also to Balinese contemporary art. I believe that Suaka’s and my collaborative works are a consensual synthetic practice benefitting both he and myself. I view this as synthesis, not orientalism. Through our collaboration, I am able to realise ideas about the provocative capacity of beauty that I think are important in contemporary Western cultural debate. Suaka is able to realise an idea important to his Balinese Hindu religious beliefs: lingga-yoni.

I am neither Balinese nor a scholar of Bali, who contributes to accumulative knowledge about Bali. But I do empathise with the processes of Balinese art and design. My own research relates to the agency of beauty itself, which I certainly experience in Bali. At the same time, it is possible for those wishing to extract Balinese Hindu readings from my works/collaborative works, including the Hindu ideal of lingga yoni, to do so.

This article is adapted from Chapter Five of Mary Lou Pavlovic’s doctoral exegesis Provoking Beauty: A Studio Research Project Examining the Provocative Dimensions of Beauty in Art Today (Monash University, Melbourne, 2015.) The chapter examines how the people and environment of Bali impacts on her studio work.

Author

Mary Lou Pavlovic is an artist who lives and works in Bali. Represented by Tony Raka Gallery, Bali, in 2018 Pavlovic was awarded an Apexart New York Franchise exhibition to curate an exhibition about artists and prisoners (Dipping in the Kool Aid) in Bali, and has staged a solo exhibition in Bali, Walking in Bali, both at Tony Raka Gallery.

Mary Lou Pavlovic is an artist who lives and works in Bali. Represented by Tony Raka Gallery, Bali, in 2018 Pavlovic was awarded an Apexart New York Franchise exhibition to curate an exhibition about artists and prisoners (Dipping in the Kool Aid) in Bali, and has staged a solo exhibition in Bali, Walking in Bali, both at Tony Raka Gallery.

Further reading

Artaud, Antonin. ‘Sur le Theatre Balinais vu l’Exposition Coloniale.’ Nouvelle Revue Francaise. 217: 655–658. 1931.

——— Mary Caroline Richards (trans.) The Theatre and its Double. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. 1958.

Bicego, Barbara. ‘A Kitten is Falling off the Roof in Bali. How Should I/We Respond?: Ethical Decision Making by Australian Women in Bali’. Conference Paper. Bali in Global Asia: Between Modernisation and Heritage Formation. Denpasar: Udayana University. 16–18 July. 2012.

Boon, James A. Affinities and Extremes: Crisscrossing the Bittersweet Ethnologies of East Indies History, Hindu-Balinese Culture and Indo-European Allure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1990.

Braginsky, Vladimir. ‘Rediscovering the Oriental in the Orient and Europe: New Books on the East-West Cultural Interface: a Review Article.’ Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. London: Cambridge University. 1997. Vol. 60. Issue 3: p.511–532.

Covarrubias, Miguel. Bali. London: Oxford University Press. 1972.

Cuetto, Barbara. What Lasts from the Site-Specificity? New Practices in Monumental Museums of the XXI Century. Autonomous Department. Accessed December 30, 2014.

Eiseman, Fred B. Jr. How Balinese People Express Ideas. Jimbaran, Bali. 2010.

——— Things I Wish Someone had Told Me When I First Came to Bali. Jimbaran, Bali. 2007.

Hickey, Dave. The Invisible Dragon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2009.

Kant, Immanuel. James Creed Meredith (trans.) The Critique of Judgement (1790). Oxford: Clarendon. 1952.

Lefferts, H. Leedom. ‘Southeast Asian Textiles: New Research and Writing.’ Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 23. 2. London: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Department of History, National University of Singapore. 1992: p.405–417.

Marajaya, I Made. Tri Hita Karana A Conception in Conducting Balinese Arts. Denpasar: Institut Seni Indonesia. 2010. Accessed March 9, 2012.

Maxwell, Robyn J. Textiles of South East Asia: Tradition, Trade and Transformation. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, Oxford University Press. 1990.

Merriam Webster Dictionary. Accessed December 10, 2014.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. Beauty and Art 1750 – 2000. Kindle Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005.

Rai, I Wayan. 2001. ‘Rwa Bhineda dalam Berkesenian Bali’. Jurnal Mudra. No. 11. Tahun IX Augustus Denpasar: STSI Denpasar. 2001.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. London: Penguin. 1977.

———Orientalism. New York: Vintage. 1978.

Savarese, Nicola. ‘1931. Antonin Artaud sees Balinese Theatre at the Paris Colonial Exhibition.’ The Drama Review. Vol. 45. Issue 3. Fall. 2001: p.51–77.

Spruit. Rudd. Artists on Bali. Amsterdam: Pepen Press. 1995.

Sontag, Susan. Under the Sign of Saturn. New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. 1980.

Taliaffaro, Charles (ed.) Phillip L. Quinn (ed.) A Companion to Philosophy of Religion, Second Edition. Blackwell Reference Online. 1999. Accessed March 5, 2012.

Utomo, Agus Mulyadi. I Made Radiawan. I Made Jana. Seni & Ornamen Tradisional Bali. Denpasar: Fakultas Seni Rupa dan Desain, Institut Seni Indonesia Denpasar. 2012.

Vickers, Adrien. Bali: A Paradise Created. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing. 2012.

——— ‘Bali Rebuilds its Tourist Industry.’ Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia and Oceania. Vol. 167 (4) October 2011: p.459–482.

Yudha, I Made, Bendi. ‘Formal Symbolization Within Spatial Imagination.’ Mudra Journal of Art and Culture. Denpasar: Indonesia Institute of the Arts. 2010.

Comments

Hi thank you! I am looking for the offical name of the flower water bowls. I have found the terms Rangoli and Kolam but these are usually directly on the floor and use spices and cereals. Is there an official name for the flower water bowls?

Thank you!