- Photo: Libia Murillo

- Photo: Libia Murillo

- Photo: Libia Murillo

- Photo: Libia Murillo

- Photo: Libia Murillo

- Photo: Libia Murillo

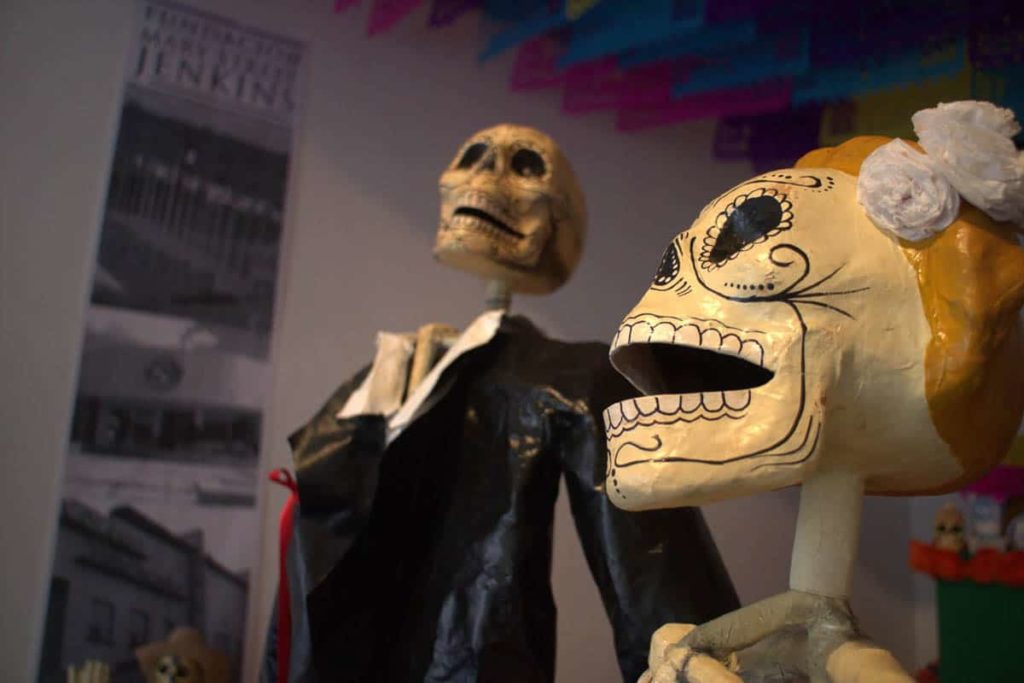

Smiling and dressed in the best clothes that artisans could make them, these “gringos” watch attentively to visitors who, for the most part, have never heard about them, although it is difficult to escape their legacy in these parts.

(A message to the reader in English.)

(A message to the reader in Spanish.)

Skinny and elegant, the cardboard skulls of William and Mary Jenkins welcome the people who look at the offering that the Capilla del Arte dedicates to them in the 2015 season of the Day of the Dead. The cultural space, administered by the Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP), participates in the second edition of Corredor de Ofrendas, an initiative of the municipal government that this year decided to celebrate important figures in the history of Puebla, a Mexican city located just over 100 kilometres from the capital of the country.

Ignacio Zaragoza, the famous general who led the Mexican army to victory in the battle against the French in this city on May 5, 1862, as well as Fray Julián Garcés and Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, two of the most important Catholic hierarchs in the history of the so-called Angelópolis, they are some of the 10 figures to which the same number of private and public venues dedicate their offerings on this occasion as part of the Offerings Corridor.

In Mexico, the tradition of the Day of the Dead offerings is as diverse as the country itself. Each region and state celebrates it in a different way, although the general idea remains: to remember and celebrate those who are no longer there; to create a link between the world of the living and that of the dead. With its 25 square meters and more than 150 pieces of paper and a dozen objects that belonged to the Jenkins couple, the offering mounted in Capilla del Arte was, according to the visitors themselves, one of the most attractive and complete of all the exhibits.

And how not to be impressed with the work of José de Jesús Hernández and Libia Murillo, the master craftsperson who gave life to the story of a character as complex as William Oscar Jenkins, one of the most affluent and important businessmen of Mexico during the first half of the twentieth century. Composed of a three-storey altar more than three meters high that alluded to the Holy Trinity, Jenkins was there, in each and every one of the elements that caught the eye. From his birth in Tennessee, United States, and his migration to the neighbouring country of the south at the dawn of the last century, until his death because of a heart attack, represented by a red ribbon that connected the heart of his cardboard figure with the arm. And although some will have escaped the symbolism, an element that inevitably brought a smile to all the people who noticed him, was the pair of tennis shoes that hung next to the central figures of the assembly, because, as every good Mexican knows When the time comes, it’s time to “hang up the tennis shoes.”

“Not only was it an offering to a historical figure,” Libia recalls three years after investing almost a hundred days in the development of this monumental work, but the opportunity to “experience his work inside the city and see everything he did among us.” As with these tasks, mastery is not enough to achieve good results. Therefore, before engaging in the task, artisans investigated electronic sites, newspaper archives and people who knew the deceased. Thus, they discovered, for example, that William enjoyed a game of chess with his son-in-law and a good tennis match at the club he helped found, that every morning he drank freshly collected milk at his farm on the outskirts of Puebla—today converted into shopping center—and that his milkman took him to the heart of the city. They also discovered his beginnings in the textile industry, from the seller of socks that he transported in a cart, to a magnate in the industry and then also to the Mexican film industry and the sugar business. All this, as well as its support to Catholic missions, the Red Cross and educational institutions such as the UDLAP itself and the American School of Puebla, appeared through paper figures, photographs printed in large format, banners or objects that belonged to him. He owned the art nouveau building that served as the first departmental store in Puebla and that decades later would become the headquarters of the university cultural space that housed his offering that 2015.

Except for those inquisitive about history or those whose relatives worked for him directly or on the charitable foundation that bears the name of Mary, most visitors knew about Jenkins after hearing the explanation of the guide or glancing at the cards that included the plan of the whole exhibition with the references and meanings of the objects arranged in the middle of carnival of objects and that sea of more than 300 paper flowers. In addition to keeping alive the tradition of Day of the Dead, in this way Capilla del Arte brought the public closer to the history of their city and country. It also approached the medium of cardboard that is rarely displayed in institutional exhibition spaces. This support for local crafts was reinforced by the works of art that shared space with the offering.

As much as the senses were awakened by the aroma of the cempasúchil (marigold) flower and the copal, before the eyes were stimulated by the multicoloured cut paper or by the vases that represented the children and the clay jars that did the same with the grandchildren, before the past surfaced in the memory upon seeing the mechanical typewriter and the hats that belonged to the honoree and that his family lent for the occasion, the visitors discovered the pieces of the exhibition Arte / Sano ÷ Artists 3.0 which reinforced the value and respect for the meticulous craftsmanship of Murillo and Hernández.

Every offering should be a symbol of the life of the people to whom it is dedicated, but also a bridge with their families, considered Libia. “It was moving to see the grandchildren and the son who was still alive at that moment while they contemplated the offering and said without hesitation ‘This is the life of my grandparents, of my parents’.”

Author

Alonso Pérez Fragua is a Mexican cultural journalist and arts administrator. He was responsible for exhibitions of the Puebla mayor’s office, a period in which he was in charge of Picasso, the infinite stele, a show that included original work by Pablo Picasso. He previously coordinated the Capilla del Arte, a space where he was in contact with exhibitions from Mexican institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MAM), the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC) of the UNAM and the Museo Tamayo, as well as art shows from abroad. He currently collaborates with the journalistic webpage Lado B and conducts research on audiovisual productions distributed through digital platforms such as Netflix, this as part of the Master’s Degree in Cultural Studies of the Paul Valéry University of Montpellier, France.

Alonso Pérez Fragua is a Mexican cultural journalist and arts administrator. He was responsible for exhibitions of the Puebla mayor’s office, a period in which he was in charge of Picasso, the infinite stele, a show that included original work by Pablo Picasso. He previously coordinated the Capilla del Arte, a space where he was in contact with exhibitions from Mexican institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MAM), the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC) of the UNAM and the Museo Tamayo, as well as art shows from abroad. He currently collaborates with the journalistic webpage Lado B and conducts research on audiovisual productions distributed through digital platforms such as Netflix, this as part of the Master’s Degree in Cultural Studies of the Paul Valéry University of Montpellier, France.