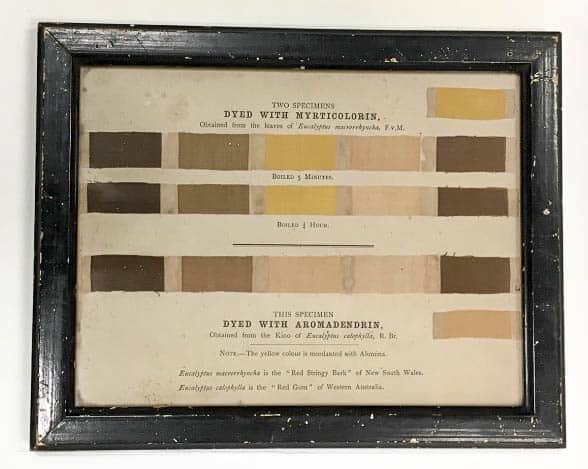

- Henry Smith’s experiments with Eucalyptus, 1918, MAAS Archives, Papers of H G Smith, MRS 310-2, Dyeing Experiments, c.1918, Sydney, photo: Liz Williamson

- Liz Williamson, Rose round, 2011, photo: Ian Hobbs

- Henry Smith’s experiments with Eucalyptus, 1918, MAAS Archives, Papers of H G Smith, MRS 310-2, Dyeing Experiments, c.1918, Sydney, photo: Liz Williamson

This paper traces the visionary idea of establishing a textile dye industry during the early years of British settlement in New South Wales using imported and indigenous plants. Initially, my research involved the contemporary use of local plant colour for Local Colour: experiments in nature exhibition which I curated for the UNSW Galleries in Sydney in 2018, but increasing I’ve been drawn to archival records of dye experiments and the colours found in Australian plants.

From early settlement, botanists, chemists and entrepreneurs experimented with colours sourced from native plants or other sources, with many recognizing the potential for an industry. The significance of these early experiments in Sydney Cove was that it was 70 years before William Henry Perkin’s accidentally discovered aniline purple in 1856, the first synthetic dye to be successfully replicated. For over seventy years the colony relied on natural sources for colouring cloth; longer, considering the time the new dyes would take to reach Australia (assumed to be the 1870’s). Sources of dye were either indigenous to the country, grown locally, traded or imported.

Following the mapping of the eastern coastline by Captain Cook in 1770, the British were interested in Terra Australis, the great southern land as a penal colony and a source of natural materials. Cook and his naturalist, Sir Joseph Banks, had travelled to New Zealand in 1769 / 1770. Captain Arthur Phillip, in charge of the first fleet of convicts, had been commissioned to investigate the advantages of “the flax plant found on the islands not far distant from the intended settlement, for clothing of convicts and other settlers and also maritime purposes”. However, New Zealand flax was not found on the mainland and what was grown was of inferior quality for intended purposes.

Prior to arriving in Sydney Cove in 1788, Philip purchased cochineal insects and prickly pear plants in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, observing the breeding cycle of the insects in his cabin on the journey to Van Diemen’s Land. Cochineal dye is obtained from the crushed bodies of a particular scale insect of Mexican origin (dactylopius coccus) that lives on the pads of prickly pear cacti, feeding on the plant’s moisture and nutrients. The bugs are collected by brushing them off the plants before drying and crushing prior to dyeing. In the late 1780s cochineal was widely used to dye cloth, especially the red coats of soldiers and marines. It gives a range of intense reds, scarlet to crimson like no other dye and in the late 1700’s trade in cochineal had “returned great riches” to Spain and Portugal, the principal trading countries.

Michael Pembroke’s 2013 biography Arthur Phillip, Sailor, Mercenary, Governor, Spy states that Phillip thought that their breeding would be “a great advantage for the nation” and plants infested with cochineal insects were to be the foundation of a cochineal industry in the colony. Sir Joseph Banks, then president of the Royal Society in London, later developed plans for a cochineal industry in New South Wales. Sadly, the wild cochineal bugs collected by Phillip did not survive in the humid Sydney climate although the climate provided an ideal environment for the prickly pear to flourish.

In the 1790s most clothing was still hand woven. The industrial revolution had advanced cotton spinning equipment, only with woollen and worsted yarns still being handspun. Woven fabrics were woven by hand as the power loom was still being developed although it had been patented. While there were attempts to establish weaving in the colony it essentially relied on imports of cloth, both plain and coloured. A portion of the textiles imported into New South Wales was from England, with the majority from India as they were cheaper in price.

Fabrics listed in the cargo manifests of 1790’s include knitted hose dyed black with logwood; Blue Gurrah handwoven in India dyed with indigo and used for working clothes; broadcloth, a heavy woollen cloth; fine muslin cotton from India and many other types.

As the British settlers were seeing Eucalyptus trees for the first time there was great interest in ascertaining their properties. Dennis Considen (unknown – 1815), was a surgeon on the First Fleet who experimented with the therapeutic possibilities of Australian plants and undertook pioneering work with eucalyptus. Considen experimented with oils and preparations from red gum, yellow gum and peppermint gum were administered to the sick to alleviate dysentery, scurvy and other diseases in the settlement.

Following the early settlement, botanist Charles Fraser arrived in Australia in 1816 the same year as the Sydney Botanic Gardens were formally dedicated in Sydney and was appointed superintendent, later colonial botanist. In December 1827 he established the “List of plants cultivated in the Botanic Gardens that are used in ‘commerce and medicine’.” Of the 69 plants included, many were for dyeing cloth namely Woad (isatis tinctoria or dyers woad) for blue; Logwood (haematoxylon campechianum) for purples to black; and Dyer’s fustic (morus tinctoria) for yellows. Fraser noted that the state of acclimatization of Woad, Logwood and Fustic in Sydney was “perfect”, but “delicate” for Indigofera tinctoria. However, Indigofera australis, a local species of indigo was not mentioned in early references.

Simeon Lord (1771 – 1840), having stolen pieces of cloth, muslin and calico, was sentenced to transportation to New South Wales for seven years. Emancipated early, in 1812 he attempted unsuccessfully to manufacture dyes from local sources. In 1815 Lord opened a woollen mill at Botany, the first mill in Australia run by private enterprise for making, fulling and dyeing coarse cloths, blankets and flannels to the colony. Known as the Merchant of Botany Bay, Lord’s 15 July 1816 letter to Governor Macquarie documents his request for “copperas and alum as mordants” for his experiments with native flora to “extract the dyes” as the government “was interested in the efficiency of the dyes procured from woods and shrubs of the Territory”.

Lord’s fulling mill at Botany undertook a range of processes for cloth including burling (repairing greige cloth), milling (felting or fulling cloth), dyeing, dressing and finishing cloth woven and manufactured at the female Government Factory at Parramatta. One letter state’s “that the cloth shall be of a dark brown colour equal to a pattern hereto annexed but a few shades darker…” In 1819 Lord backed a successful experiment to extract tannin from wattle and Tasmanian seaweed while in 1820 his samples of textiles, hats, stockings and leather, which the colony commissioner estimated as “a threat to British manufacturers”. Lord’s factory continued to operate until 1856 when the government resumed land and water rights. Lord regarded his work of cloth manufacturing and dyeing his greatest contribution to the development of the colony.

In the early 1800’s India was the main source of the colony’s textiles, for furnishing and for clothing, from the meanest quality to the finest, all hand woven. India was looked to for fashion in addition to the convenient supply of piece goods—but of the thousands of yards brought in hundreds of cargoes from India, at least three cargo ships a week, almost nothing remains. This trade was surpassed in the 1840s by cheap woven and printed cottons from Britain, results of further industrial innovations.

Although not in NSW, the next person to experiment with local plant dye colours was Baron Ferdinand von Mueller (1825 – 1896) director of Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens from 1857 to 1873. Most records note that von Mueller was the first to publish a full account of dyes from Australian plants presented at the 1867 Intercolonial Exhibition of Australia, held in Melbourne in 1866/67. Churchill, director of the Melbourne Botanical Gardens from 1971-85, notes in 1981 that all these dyes were water-soluble extracts from bark and collated by Mrs Anthelme Thozet from Rockhampton in Queensland, providing von Mueller with a comprehensive account of plant dyes, mordants and their effect on wool, silk and cotton.

The intensity of dye varied with the colours strongest for wool and weakest for cotton. The only exceptions to this were from the commonly experienced gradient were the infusions from sarcocephalus cordatus, the canary wood in the family rubiaceae (the madder family) and alstonia constricta in the apocynaceae (the periwinkle vinca Family) where cotton, silk and wool were dyed to an equal colour intensity. Several have written that von Mueller had discovered the beautiful reds of Eucalyptus cinerea but I’ve not been able to verify this. He was, however, responsible for exporting eucalyptus seeds around the world, advocating their planting as a measure to combat malaria.

In Sydney in 1887, Joseph Henry Maiden (1856 – 1925) announced to the Royal Society of New South Wales that a yellow colouring matter existed in the leaves of the “Red Stringybark” Eucalyptus macrorhyncha. Maiden published The Useful plants of Australia, including Tasmania in 1889 which included a chapter on dyes from Australian plants. He stated “Australia certainly does not appear to be a land which can boast of its native vegetable dyes. But it is only fair to observe that practically nothing has been done in the way of experiments with our raw dye-stuffs”. Maiden’s dye chapter listed 35 plants, their botanical name, common name, location and a very brief statement of the colour, such as Eucalyptus corymbosa. This dark coloured kino (resin) contains a rich dye material of a reddish colour.

Henry Smith (1852 – 1924) worked at the Technological Museum in Sydney and trained as an organic chemist. Smith extracted yellow dyes from several species of NSW eucalypts in 1897. He believed that these dyes could be of great economic value to Australia and he continued the work began by Maiden in documenting the yellow dye extracted from the leaves of Eucalyptus macrorhyncha or Red stringybark. In 2017, I examined Smith’s 1918 dye experiments in the Museum of Applied Arts & Science (MAAS) from Eucalyptus macrorhyncha and Eucalyptus calophylla (Western Australian Red Gum) on cotton and using alum as a mordant. 100 years after being dyed, the cloth showed strong yellow to brown colours.

Documents show that the archives created by Baron Ferdinand von Mueller (1880) and Smith & Maiden (1887) show dye experiments undertaken to test the potential for an industry in Australia; both celebrating the wealth and diversity of local plants. Smith & Maiden tested eucalypts in the Sydney region stating “that Eucalypt dyes could be of great economic benefit to the colony of Australia. Smith, with his colleague Maiden and from 1897 with R. T. Baker, researched the chemistry and botany of Australian plants yielding volatile oils which did become a small industry.

Overall, research in the first hundred years of the colony laid the idea of the possibility of a dye industry from Australian native plants. After this period, dye experiments were carried out by weavers exhibiting work at the Melbourne Arts and Crafts exhibition in the 1910s and by Eady Hart in Ballarat in the early 1920s. Jean Carman was the first to systematically document the colours of Australian eucalypts testing over 450 species. Liaising with State Forestry Departments in Australia for plant material, Carman published an extensive survey of eucalyptus dye colours in 1978 titdyled Dyemaking with Eucalypts. It listed of over 300 eucalyptus species, locations, mordants used and colours obtained; Carman also believed in a local dye industry as have others who have continued plant dye research. The 2018 exhibition, Local Colour, illustrated the vitality, breadth and beauty of this practice, and highlighted the resurgent international shift towards natural dyes, “slow” textiles, the handmade and a holistic making practice.

Author

Liz Williamson is an academic and weaver based in Sydney, Australia. Although her first weaving experiments in the late 1970s included hand-spun wool dyed with local plants, it wasn’t until early 2000 that she experimented with traditional dyes of Logwood, Indigo, Henna and Cochineal alongside several Eucalypts species. Her current weaving includes materials coloured with Eucalyptus cinerea and Eucalyptus pilularis. In 2018 she curated ‘Local Colour: experiments in nature’ for UNSW Galleries in Sydney. Williamson is an Associate Professor at UNSW Art & Design, Sydney and regularly takes groups of people to India, introducing them to artisan handmade textiles.

Liz Williamson is an academic and weaver based in Sydney, Australia. Although her first weaving experiments in the late 1970s included hand-spun wool dyed with local plants, it wasn’t until early 2000 that she experimented with traditional dyes of Logwood, Indigo, Henna and Cochineal alongside several Eucalypts species. Her current weaving includes materials coloured with Eucalyptus cinerea and Eucalyptus pilularis. In 2018 she curated ‘Local Colour: experiments in nature’ for UNSW Galleries in Sydney. Williamson is an Associate Professor at UNSW Art & Design, Sydney and regularly takes groups of people to India, introducing them to artisan handmade textiles.

Comments

Hello Liz,

Thank you for your article, it is very interesting to note that people have been researching the possibilities of Eucalyptus dyes for such a long time. We are still at it! I have a copy of Jean Carman’s book and it is a treasure trove of information although some of the mordants she used are scary.

I use Eucalyptus dyes for my textile work and never tire of the variety of colours.

Thanks again.

Kind regards,

Jane

Thank you so much for this interesting article. I am an historian (MA in Australian history ) and a spinner and knitter. I now live in Tasmania where there is a rich resource of natural dyes and the most beautiful wool on earth.