Lacquer is a gift of the ancients that is largely forgotten today. Sachiko Matsuyama is convinced of its value not just for its redolent surface but also as a bond between people and nature. She finds an inspiring future for lacquer in the work of Takuya Tsutsumi, in partnership with an Australian surfboard maker.

(A message to the reader.)

A Japanese artisan attended the film screening of Noosa Festival of Surfing 2019, in Australia, feeling the adrenaline of a new future.

One of the films was about a special surfboard made with the strong support of the legend Australian surfboard shaper Tom Wegener. It featured their united passion: caring thoughts for Mother Nature. The artisan’s “traditional” culture has probably never been associated with surf culture before. What everyone at the film screening witnessed, however, was the clear message that cherishing local culture means pursuing universal values.

Now neglected, urushi (Japanese natural lacquer) was once an essential part of Japanese culture. While the urushi tree was originally grown in China, it is known to be planted during Japan’s pre-history and has been used for over 10,000 years. In ancient days, it was viewed as a sacred material: the sap of the urushi tree oozes like blood when the tree is wounded. Urushi has been used to top-coat a variety of surfaces, including temple and shrine buildings, tea ceremony tools, bowls and everyday tables.

The mainstream image of urushi in modern society, however, has never gone beyond the traditional. It is considered only for the use of trained artisans to make the most elegant fine crafts for the exclusive use of high-end clients. Or, otherwise, it is just the material for the preservation of the cultural heritage. Its allergic properties are a problem too. Before being processed, it has a poison that causes a rash on the skin, as commonly seen with sumac family. The trees are now planted far from human settlements.

Declining in the shift of values

Takuya Tsutsumi is the fourth generation successor of Tsutsumi Asakichi-ten, one of the major urushi refining companies in Japan. He processes raw urushi, which is the sap of the urushi tree, by filtering and stirring to adjust colour, shininess and thickness to a perfect preference for the use by each urushi-painting artisan.

Urushi has special biochemistry. It hardens when its main component urushiol oxidizes with moisture in the air, thanks to the oxidase called laccase. The artisan evens out components of urushi for lustre and thickness by stirring and vaporises the moisture in it with heat to control the speed of hardening.

97% of urushi is now imported from China. Japan became so dependent on the production in China because its own society has experienced aging, urbanisation and rise of labour expenses. Needless to say, these are also all happening in China now.

When Takuya joined his family business in 2004, the total amount of urushi consumption in Japan was 100 tons, which was already considered very low. It dropped to 42 tons in 2017 and is now 36 tons.

There are particular reasons for the decline of urushi. Modernity has taken young workers away from the forest and mountains to seek employment in the cities. The pursuit of industrial efficiency has replaced urushi in everyday tablewares with cheap alternatives made of plastic. Each region used to have, and may still barely have, natural resources rooted in its cultural and natural climate that provide our everyday crafts including pottery and urushi lacquerware. But human hands have forgotten the subtle delicacy necessary to appreciate fluctuation and depth of beauty that comes from nature. Creating this distance between humans and nature only enforces capitalist, urban-centred social structures, like a vicious circle.

While what worried Takuya might have started from an industry-specific concern around his family business, doesn’t this situation reflect today’s world in general?

Circles of communities: what we are really losing

Many of us who consider craft just as another aesthetic form of art or outcome of hands-on creativity that belongs to the individual maker, tend to forget the fact that the handmade craft in everyday life is actually also a way of connecting communities of producers and consumers.

Users and makers exist in a self-sustaining circle. Long-life objects are designed to be repaired when they are made with authentic natural materials. They enable a cycle between users, often from parents to children. There is a circle of hard-working artisans with different kinds of expertise, as well as care-takers of forests, farms, and lands where materials are born. This is ikiteiru kogei, living craft.

In the case of urushi-ware (tableware made with urushi), we need not only an urushi painter, but also an urushi refiner like Takuya, an urushi sapper, a woodworker and a lumberjack for the base of urushi-ware, and people who help urushi trees to grow by clearing undergrowing weed. Many of them need blacksmiths and brush makers to make special tools for each profession.

Like any other craft form, it is not only the fashion market that is preventing urushi being passed down to the next generation. It is not a simple question of tradition versus modernity. Because of the shift in values just mentioned, we are losing the connections between people. The problem was too deep and he did not know what to do about it.

Re-noted potentiality fresh in 10,000 years

When he was younger, the love for nature encouraged him to pursue an academic education in farming and a career in the food supply industry in Hokkaido, where he thought he could get away from his family business. His father eventually asked him for support to carry out their business, though neither the father nor the son had thought the son should take it over. Later, he became a father himself. Nature that had been his private passion then became something he wished to preserve for his son.

Indeed the 2010s, when he became the successor of the urushi tradition, has been also an era of the great awakening to what is happening to Mother Earth. Major natural disasters like Fukushima occurred, and there has been no single day when we do not see any article, image and video about animals who were choked to death with plastic, burning forests, and the heat waves.

At first, crafts including urushi-ware in our daily life were replaced by plastic and synthetic resin. We now fear for the health of living beings and their planet. Returning urushi seems a positive step. He had never thought his family business could be an inspiration in response to the plight of the planet today. There was certainly an aspect of urushi that has been too much underestimated for the last 10,000 years of its history until we came to the very edge!

Meeting the master surfboard shaper

In the late 2000s, Takuya watched a movie Sprout featuring various surfers including Tom Wegener and came to know about him. Wegener revived the ancient alaia surfboard and advanced the building of wooden boards with paulownia and cork, which established a new genre in surfboard design. He explained his motivation to explore green methods was simply care for nature that should be left for his children. He has been seeking sustainable materials for making surfboards with repairable methods.

Takuya admired Wegener and was determined that they meet!

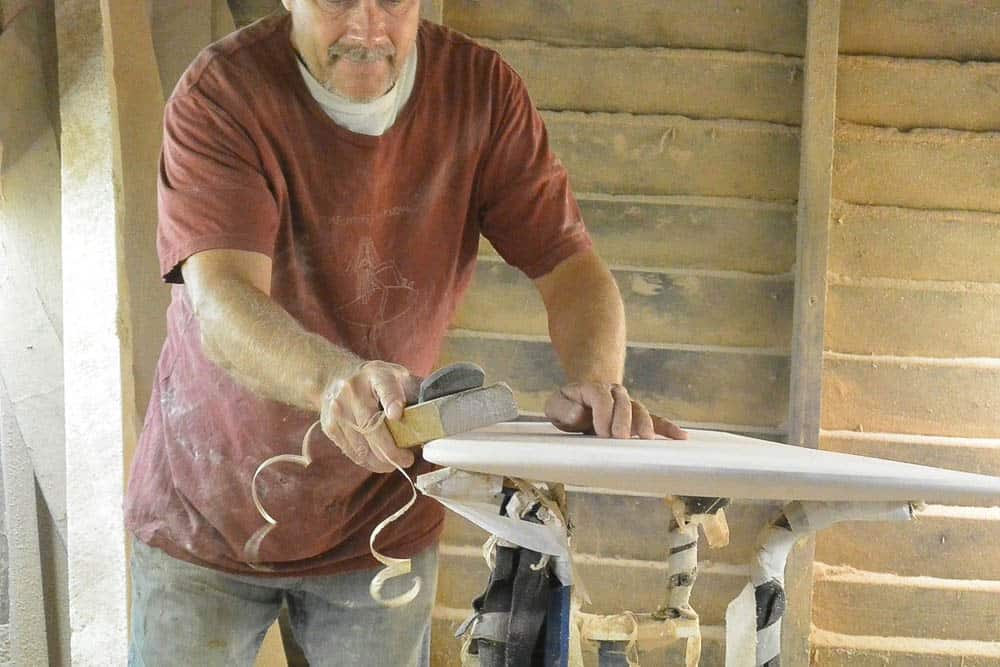

In 2018, Takuya managed to approach Wegner through his friend to propose making an urushi alaia and a film featuring the project. Determined, he went to Noosa to meet Wegener with a sample piece and found that Wegner shared his passion. Wegener made an alaia surfboard from one solid paulownia and Takuya had it painted with urushi. The short documentary film followed the production process, reflecting the shared wish from both hemispheres to preserve what is beautiful for future generations.

On the night of 7 March 2019, at the Noosa Festival of Surfing 2019, Takuya witnessed a passionate audience of about 40 people drawn to the connection between “surf culture” and “natural conservation”. The ancient craft material used in the production of a classic tea ceremony in Japan is now certainly recognised by the young Australian, who appreciate the beautiful but wounded planet, even if they are not familiar with the traditional crafts of Japan.

Next challenge: connecting communities to grow urushi trees for culture

In 2015, the Agency for Cultural Affairs determined to use domestic urushi as an essential material for the policy of preservation and repair of buildings designated as a national treasure and important cultural property in order to help protect Japanese urushi whose production is decreasing. Recently human resource training has been developing for urushi production, aiming for a stable supply.

This was definitely a tailwind for Takuya’s family business. He wishes, however, that this material could remain as part of real “culture”. Focusing only on the preservation of cultural heritage from the past should not be called “culture” in a real sense. It has to be alive in the present time.

In a living culture, small children appreciate their eating habits by holding urushi soup bowls with their small palms, feeling the texture of nature. Such everyday utilitarian objects age over the years and can be repaired and used for a very long time.

Urushi trees only become ready to be tapped when they are more than ten years old if they grow well. If chains of people around urushi including tappers and refiners like Takuya himself cannot survive for this coming ten years, then urushi would not be sustained as a rich culture where humans interact with objects and food in a sustainable manner.

There has been an initiative to bring back authentic urushi food bowl in the kindergarten to nurture children’s appreciation for food and people who are part of the society supporting their everyday life.

To restore its supply, there have been struggles to acquire suitable lands, labour cost for clearing undergrowing weed, and professional education and financial autonomy of urushi tappers. In this monetary economy, efforts to keep the product at an affordable price weighs on labourers in each step of urushi production. A low wage compromises the sustainability of production.

The sustainability of urushi culture would probably be possible, Takuya thinks, only if we come up with a structure beyond the monetary system. We need to develop some kind of economic system in which people share labour to grow urushi trees together in small local communities. Meanwhile, global communities who support green actions and choices for health would help to raise people’s awareness of the value in urushi with fresh eyes.

Locally respectable values should become universal, he believes. And his trials continue.

Author

Craft Culture Coordinator Sachiko Matsuyama founded monomo in January 2014 with a wish to share Japan’s rich craft culture with the global community. Sachiko travels throughout Japan meeting master artisans whose work is grounded in a connection to nature and the fertile traditions of their craft. She supports collaborative productions between Japanese international artisans in various traditional crafts and international creators, while develops programs and tours for people look at the craft as a mirror of culture.

Craft Culture Coordinator Sachiko Matsuyama founded monomo in January 2014 with a wish to share Japan’s rich craft culture with the global community. Sachiko travels throughout Japan meeting master artisans whose work is grounded in a connection to nature and the fertile traditions of their craft. She supports collaborative productions between Japanese international artisans in various traditional crafts and international creators, while develops programs and tours for people look at the craft as a mirror of culture.

松山 幸子 プロデューサー monomo代表

日本の豊かなクラフト文化を世界と共有することを目的に、2014年monomo設立。自然と繋がり豊かな歴史に根ざす手しごとに取り組む職人たちを全国に訪ね、工芸の後ろに潜むストーリーを発掘する。日本の伝統工芸の職人たちと海外のクリエイターとの間のコラボレーションをサポートする一方で、工芸は日本の社会、価値観、意識を映し出す鏡であると位置づけ、教育プログラムやツアーを企画している。

Comments

I really enjoyed reading this article. It is so rich in details about the process, the need, the discovery and how a craft can help repair not just old objects and buildings but also our wounded planet. It’s passionately written and a reminder of the importance of community. In our highly individuated millennial culture, the loss of community is as much a cause for concern as is the loss of the context, ideals and philosophies that created the hand-crafted objects we bring appreciation and value too.

I also share concern for the future of lacquer work in Japan. One of the problems that I have long noted with the lacquer crafters of Tsugaru (Aomori Prefecture) is their reluctance to work with other businesses. They tend to continue doing what they have always done: using lacquer in producing piece-work … a bowl, a tray, a table. I advised the local lacquer community to make connections with local housing construction companies and be imaginative and flexible in coming up with ways to include lacquer in many small parts in the overall construction of a house. This way the lacquerware becomes part of the house and not an added afterthought. Things like handrails, bathroom basins, window frames, base boards, etc. Given its anti-bacterial properties, it would be perfect in facilities for the aged … and it often brings fond memories for people. But they have been reluctant to do so. (Author of Cultural Commodities in Japanese Rural Revitalization: Tsugaru Nuri Lacquerware and Tsugaru Shamisen, Brill 2010)