- Sarra Tzijan, Seven brass spoons made from the lost wax casting method. Individually built by hand from wax, and moulded with wooden tools; in the final stage of the process liquid brass was poured into clay moulds, taking the original shape of the wax. The brass was removed by breaking the clay mould around it. The finishing process involved coating the brass in solution over flame to create a patina.

- Sarra Tzijan, Primal Casting, 2019

- Sarra Tzijan, Primal Casting, 2019

- Sarra Tzijan, Primal Casting, 2019

Sarra Tzijan recounts the journey to India that led to her work based on traditional Indian casting techniques, made during a residency in Devrai Art Village, Panchgani.

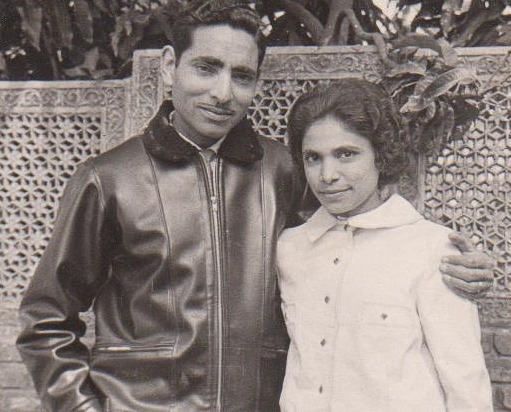

Sarra’s father Juan Smith introduces the journey.

Juan Smith tells of his journey from India.

Born in Delhi, I migrated to Australia at age two with my family in 1971. As a brown kid in a white Melbourne in the 70s and 80s, I wanted to fit in. This meant suppressing my ”Indianness” and adopting a broad Aussie accent.

Sensing an identity gap in my late teens, I started to embrace my Indian heritage and the rich beauty that it offered. I began to celebrate my Indianness. It was there, as part of my DNA, from hundreds of years of family lineage in both north and south India. My passion for India is not patriotic or nationalistic, but more an emotive identification. It’s the sense of home I get when I eat Indian food. It’s the familiarity of smells in a spice shop. It’s the stirring emotion when I hear the sound of a sitar. It’s the humanity in a bustling, chaotic, Indian street that strikes a note of beauty in your core.

By either luck or design, both my children, Sarra and Jamal, have also embraced their Indian heritage. Perhaps it is due to the stories of Ram and Sita recited to them as kids. Perhaps it’s the trip to India in their younger years. Or perhaps because India sits also in their DNA. Whatever the reason, their cultural connection led Sarra to India for an immersive experience with Dhokra, a 4000-year- old sculptural art form. Working with the local village artists, Sarra described a sense of awe at this different world, which contrasted with her Australian life, but at the same time, a sense of familiarity that consolidated her cultural resonance with India. To see my children connect with the living history of India in such a meaningful capacity gives me an immense sense of pride.

Sarra continues the story.

In explaining my practice and work I’ve always referred to the merging of traditional metalworking techniques with contemporary art and design. Without planning, the collection of objects presented in Primal Casting embodies that.

All the work in this show came from Devrai Art Village— a small hill station called Panchgani, east of Mumbai, where strangely, Freddy Mercury went to school. The Village Vessels started in India, were built from the clay in the ground, and moulded from wax sourced from local bees. They were then flown back to Adelaide and passed on to Hamish Donaldson, an Australian glassblower, who evolved them into these contrasting mixed material, new- world-meets-old-world objects. The work came out of free play, resulting in a true representation of my mixed heritage. The making and process was spontaneous, fluid, collaborative and experimental. This is how I like to make and often how the best work comes out, if you let it.

Through observation at the art village, I thought a lot about the making process. The artists there spoke of their work as naturally collaborative. It was a communal effort rather than a solo journey. They spoke of the importance of direct contact with nature and the making space. I reflected on my own studio environment that was indoors with many walls, doors and sections. The art village was outdoors, open, nestled in the trees with animals and children. There was a generous break for lunch, usually in the shade of the prominent fig tree. Wax was melted with coals, brass with large fires. Light came from the sun. Most days ended with volleyball.

My brother Jamal accompanied me during the residency, documenting the experience through film. It was special for us to be there together; we had returned back to our “old, old home”. We were making art and looking for clarity.

The feeling of arriving in India is somewhat like coming home: it’s familiar, like from lifetimes ago. Challenges came with gender, sex and roles, and I became very conscious of these things. Men and women worked separately in the art village. I worked with men and I interacted mostly with men as they were the “master craftsmen”. They created the large, complex and fine sculptures that brought more money. The women were responsible for making smaller, wearable items that generally require less refined hand skills. The women brought the men tea and they sifted the clay. Everyone seemed comfortable in their roles. I found it uncomfortable, at times.

Primal Casting is the work of many hands, all the way back to my family in India who contributed to my thoughts around identity, family and home.

Jamal Twycross-Smith concludes:

The further I go through life, the more I am understanding just how much my Indian heritage has shaped who I am, in a very unique way. The time spent at Devrai Art Village with Sarra, my sister, was a reminder of how deeply I love Indian culture. While my perspective of it is still very much from the outside looking in, I can’t help but feel a sense of belonging and pride just being there, especially when noticing small familiarities associated with my father or grandparents. What has become most apparent is that my concept of India is deeply connected to my concept of family. With the many uncertainties I face around my identity, I’m glad to have realised this.

Author

Sarra Tzijan is an emerging contemporary maker working across jewellery and sculpture. Originally from Melbourne, currently based at JamFactory in Adelaide, her practice unifies traditional metalwork skills with modern art and design. At present Tzijan is collaborating with a local ceramicist for an upcoming show CERAMIX which will be exhibited at Manly Art Gallery and Museum in May 2020.

Sarra Tzijan is an emerging contemporary maker working across jewellery and sculpture. Originally from Melbourne, currently based at JamFactory in Adelaide, her practice unifies traditional metalwork skills with modern art and design. At present Tzijan is collaborating with a local ceramicist for an upcoming show CERAMIX which will be exhibited at Manly Art Gallery and Museum in May 2020.

Comments

Thank you Sarra for keeping me motivated and aware of what is going on out there around the world. be well and keep inspiring.

Olga