- Hafu Matsumoto

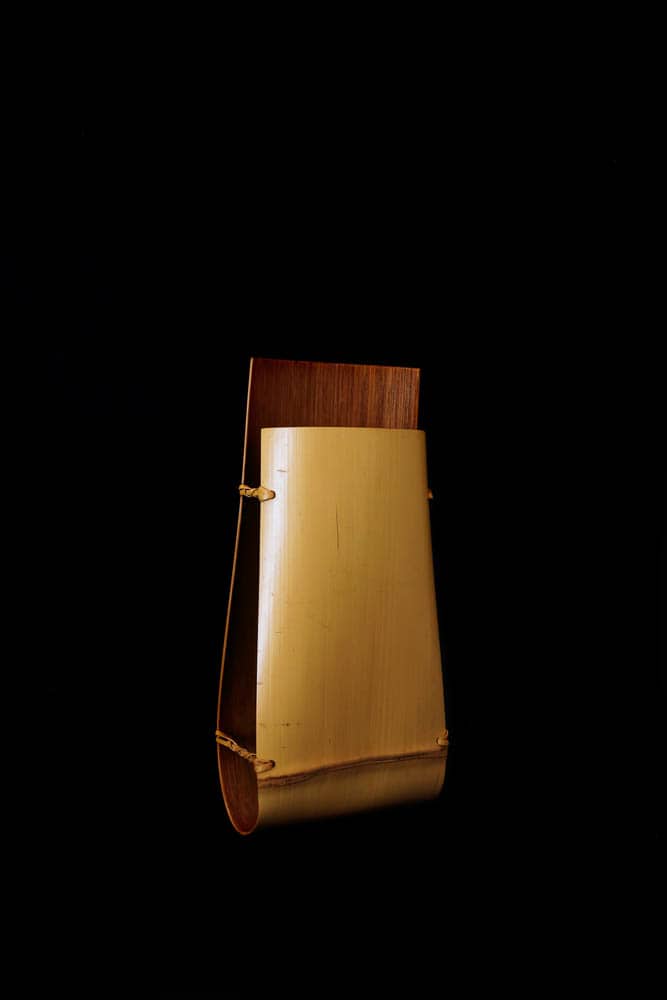

- Hafu Matsumoto, Noshitake bamboo flower vase, Angu

- Hafu Matsumoto, Noshitake bamboo flower vase

- Hafu Matsumoto, Wide Noshitake bamboo flower vase, Rokan

- Hafu Matsumoto’s garden

- Hafu Matsumoto

- Hafu Matsumoto, Kushime pattern bamboo tray, Ginryu

- Hafu Matsumoto, Kushime pattern bamboo tray, Ginryu

- Hafu Matsumoto, Kushime pattern bamboo flower basket

- Hafu Matsumoto, Sashiami Mayfly decoration box

Hafu Matsumoto practices the traditional martial art of Iaidō. He is now in his sixties and I think that having practiced kendō since his youth, he decided to practice a higher dō or “path”.

The current Japanese definition of art or geijutsu was not adopted until after the Meiji Restoration in the mid-nineteenth century. Prior to that, Japanese crafts were considered to be forms of “dō”, a term that can have almost religious connotations.

People are all guided by “something” as they make their way through life and for generations the Iizuka family, including Rokansai and Shokansai, has been guided by bamboo. This is a path in which bamboo itself serves as the teacher and every day is a struggle with one’s self.

Bamboo is a material that cannot be worked freely and artists without a true vocation will soon give it up. There is no telling how many times bamboo dealt Rokansai or Shokansai a crushing blow during the course of their careers.

From his youth, Hafu received strict training under my father, Shokansai, equal to that of the traditional martial art, and after the loss of his teacher, he has continued alone in silence, led on by the bamboo blade.

Mari Iizuka

Bamboo has played an important role in Japanese culture since earliest times. Its elegant form, its straight, hollow, green stems reaching up into the skies, symbolise purity and good fortune. In Kaguyahime (The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter), which is said to be the world’s oldest science fiction story, a bamboo is cut open to reveal a beautiful princess. The story ends with messengers coming down from the moon to take her back into space with them. Bamboo possesses a strange spiritual and magical power that leads us all towards heaven.

Hafu Matsumoto’s studio is located in the southern part of the Bōsō Peninsular, where the wind blows off the Pacific Ocean, and he listens to the sound of this wind rustling through the bamboo groves as he works. He says of his work, “Fresh, green bamboo possesses more than enough beauty on its own. I cut its life short so the least I can do is to preserve its suppleness forever by sealing it within bamboo basketry.”

As the last apprentice of Shokansai Iizuka (1919–2004, designated a living national treasure in 1982) who was himself a second-generation apprentice of the genius, Rokansai Iizuka (1890–1958), Hafu Matsumoto is exceptionally skilled and has mastered the shin, gyō and sō (formal, semi-formal and informal methods) of weaving. One moment his expression resembles that of a samurai, as he struggles with the unforgiving bamboo, then the next he will resemble a peaceful priest as he works with the material’s flexible nature. In his work, Matsumoto conforms to the golden rules that guided Rokansai and Shokansai throughout their lives.

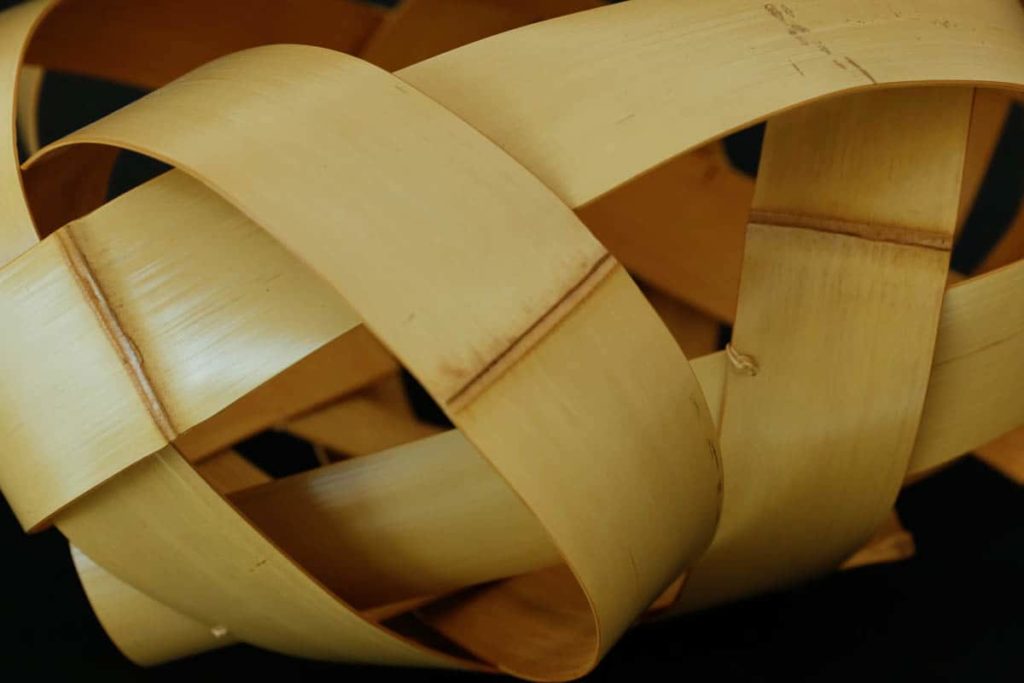

The Noshitake series, around which this exhibition structured, utilises the Sō (informal) technique that was developed by Rokansai. Its very simplicity allows the viewer to feel the vigour and refinement possessed by the craftsman. Pieces of bamboo, that have been split open then flattened by soaking them in boiling water, are bent together vigorously to create objects in which the tension resulting from the bamboo’s natural tendency to stand erect, produces graceful forms. Tension and quietude are born from the enthusiastic dialogue between Hafu and the bamboo. Hafu Matsumoto’s bamboo baskets present a new form of bamboo craft suited to the twenty-first century that will doubtlessly weave a new future for Japan’s unique traditions.

Shoko Aono

Authors

Mari Iizuka is the only daughter of Shōkansai Iizuka and the granddaughter of Rōkansai Iizuka. Seeing her father’s strict and exacting approach to bamboo weaving, she decided not to follow in his footsteps but to study sculpture and jewellery design/creation instead. In 1979 she won a prize in the De Beers Diamond Design Contest. From 1988 to 1990, then again from 1996 to 2012, she lived in Germany. Until recently she maintained Shōkansai studio in its original state as a memorial to achievements, while also working with the craftspeople of tomorrow to study the bamboo art of the Iizuka family and record it for posterity. She is currently living in Japan, writing and producing jewellery consisting of woven threads. She is a proprietor of Rokando.

Mari Iizuka is the only daughter of Shōkansai Iizuka and the granddaughter of Rōkansai Iizuka. Seeing her father’s strict and exacting approach to bamboo weaving, she decided not to follow in his footsteps but to study sculpture and jewellery design/creation instead. In 1979 she won a prize in the De Beers Diamond Design Contest. From 1988 to 1990, then again from 1996 to 2012, she lived in Germany. Until recently she maintained Shōkansai studio in its original state as a memorial to achievements, while also working with the craftspeople of tomorrow to study the bamboo art of the Iizuka family and record it for posterity. She is currently living in Japan, writing and producing jewellery consisting of woven threads. She is a proprietor of Rokando.

Shoko Aono graduated in Philosophy from the University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, and then received a Masters degree in Philosophy from Sophia University, Tokyo. In 2006 she started working at Ippodo Gallery, Tokyo and participated in La Biennale des Editeurs de la Decoration at the Carrousel du Louvre, Paris. In 2008 she moved to New York and opened Ippodo Gallery New York, where she is currently working as director. She organises numerous exhibitions and participating in art fairs throughout the USA and Europe, promoting and fostering the finest of contemporary Japanese art crafts outside of Japan.

Shoko Aono graduated in Philosophy from the University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, and then received a Masters degree in Philosophy from Sophia University, Tokyo. In 2006 she started working at Ippodo Gallery, Tokyo and participated in La Biennale des Editeurs de la Decoration at the Carrousel du Louvre, Paris. In 2008 she moved to New York and opened Ippodo Gallery New York, where she is currently working as director. She organises numerous exhibitions and participating in art fairs throughout the USA and Europe, promoting and fostering the finest of contemporary Japanese art crafts outside of Japan.