- Retro fit-out in Terrior Café, Jakarta image courtesy of Lufti Hasan and Jakarta Vintage

- The retro look with recycled mid-century modern furniture, boutique in Bali

Hip cafés in Indonesia’s major towns are serving up blends rich in 1950s aroma. From furniture perched on pin-pointy legs, boutique hotels flaunt flashy angles and revivalist facades to Pertamina’s petrol stations with their tilted canopies have all brought a “retro” look to town.

The local avatar of Mid-century modern architecture, Jengki style (Yankee) is enjoying a revival. Leaving behind colonial chic, some Indonesian artists and designers have begun straying into a forgotten cultural frontier: the aesthetics of the new Indonesia. Yet the era from where this once arose: the 1950s and 60s, full of energy and diverse politics—remains in the shadows.

For almost a decade, I have travelled off-road, disregarding cultural amnesia to track down a near-invisible heritage of work, rest and play. Mountain villas, elite townhouses, churches and once-prominent public buildings reveal an alternative façade to the new Indonesia. Little-known treasures of modernist heritage feature in my recently published coffee table book Retronesia: the years of building dangerously (available on Amazon)

Going beyond images of fine buildings, Retronesia has relied upon oral history, journeying to the darker edges of living memory, where grannies and grandads reveal what was really going on in this newly liberated and optimistic nation. Upstaging President Sukarno’s monuments and public institutions, private architecture flourished, reflecting the fortunes and aspirations of new and old elites.

Volcanic Chill – Mountain Resorts

- The Piringan lakeside villa, Sarangan, east Java

- The Lubis Townhouse 1965, Tebet south Jakarta

On the lower slopes of Java’s slumbering volcanoes are countless guesthouses that once represented a one-time A-lister destination. Puncak, Kopeng, Kaliurang, all the way east to Selecta resort in Malang were all once luxury getaways.

After the fog of revolutionary war had lifted, night-time curfews were imposed leaving country roads bandit domain. Oddly, Java’s former colonial retreats were not shunned or torn down like confederate statues; rather they were revamped and polished for a new elite checking-in during 1950s. After the mass expulsion of the Dutch community during 1957-58, these sites were refitted to suit new ambitions and represented an evolved look-book for elite properties late into the 1960s.

Between 1955-58 Swiss-trained architect Oei Tjong An returned home and transformed Kopeng resort for Semarang’s new mercantile class. Palm Springs—complete with butterfly roofs, tilting beams, fancy trellises and rock work chimneys – made a guest appearance in a new Java.

Within a generation, tastes in luxurious leisure had shifted considerably. During long weekends and holidays— when volcanoes remain dormant—the general public make convoys of traffic heading slowly uphill for gatherings, parties and for a more recent leisure interest – dressing up and selfeying in the outdoors. What was once the Dutch equivalent of Indian hill stations represent a modern archaeology of a distant world where risk-taking and success were celebrated in full.

- Interior detail of once prestigious hillside villas, Kopeng Resort, Central Java

- Exterior detail of once prestigious hillside villas, Kopeng Resort, Central Java

The Improbable Home – The Tebet Townhouse

As Senayan Stadium gets ready for the 18th Asian Games this year, one of the biggest hurdles is the city’s traffic. When the complex was built in 1962 for the 4th Asian Games, the daunting challenge was the need to rehouse lots of people. Families were quickly moved and many were resettled in the new Jakarta suburb of Tebet.

Little more than swampland on the city’s southern and eastern edges, Tebet was known as tempat jin buang anak (literally, a dumping ground for genie’s children). It was an unlikely home for a first-generation diplomat, Pak Haluddin Lubis. Born to a humble Batak family in north Sumatra, Pak Haluddin had as a child dreamed of travelling westwards to study at Cairo’s Al-Azhar University.

By the 1930s the young Haluddin got himself on board a ship taking him as far as British India, where he began his studies at the alternative locus for anti-colonialism, the Deobandi Islamic school – then a peer of Al-Azhar. Amidst the chaos of 1947 he was evacuated from Delhi to Karachi in newly created West Pakistan, where he unintentionally embarked on a diplomatic career with Indonesia’s fledgeling Foreign Service.

Like most civil servants he drew a meagre salary that did not cover his living costs in between postings. Unlike others, he did not turn to moonlighting or dishonesty to make up shortfalls in income. He opted instead to resell valued foreign products like cameras, projectors and even cutlery which his family could bring back into Indonesia. A long-time car aficionado, he procured a new Fiat 1100 during his posting to Poland. This was resold in Jakarta and the proceeds used to purchase the ready-built Tebet townhouse in 1965 and provide adequate living expenses for his family.

- Ambassador Lubis back in Jakarta with his wife late 1960s. Photo Courtesy of Farida Lubis

Last Orders – The Bumi Sangkuriang

Dutch Indies revival style architecture was back in vogue when Indonesian secured full Independence in 1950. Nation building created a new Dutch monopoly enterprise that went unchallenged until the end of 1957. The Dutch technical class continued in their business as usual outlook, ignoring the warning signs and escalation under Indonesian first president Sukarno’s Indonesianisation policy push.

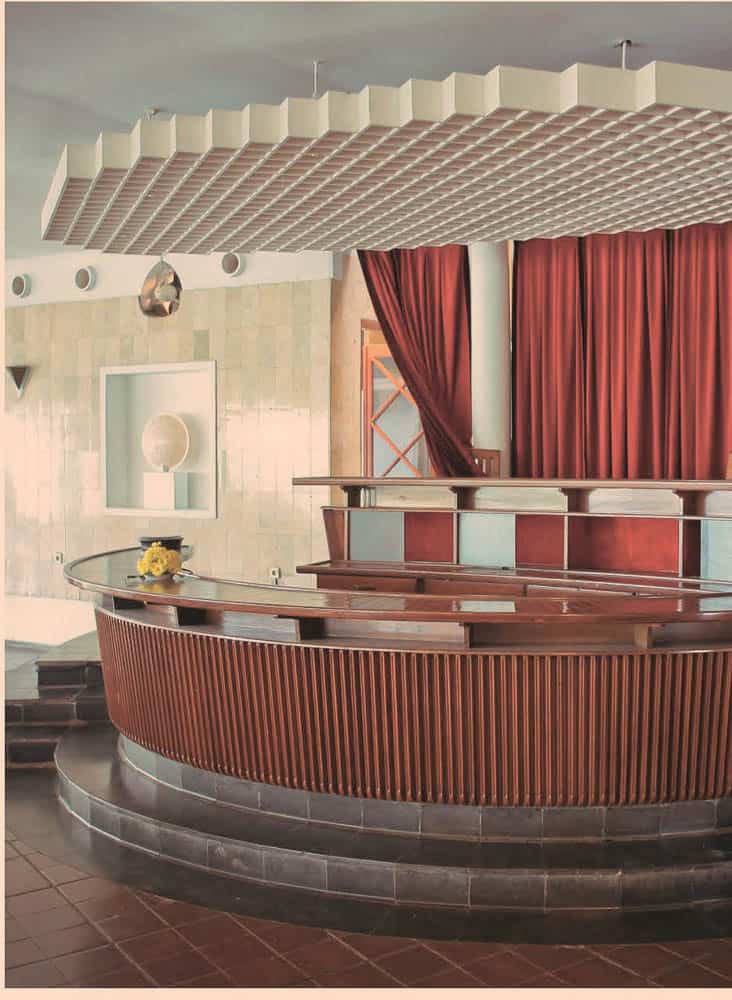

The hotel and restaurant Balai Pertemuan Bumi Sangkuriang, located in Bandung’s exclusive hillside district of Ciumbuleuit, played a supporting role in the first Afro-Asian conference of 1955 – aka the Bandung Conference. Indonesia hosted its first international conference to cement the non-aligned movement’s ideals and to hasten the global wave of decolonization.

Bandung, with its stylish hotels, cafes, and boutiques enjoyed by Europeans was the obvious host city for Indonesia’s legendary conference. Until the 1940s, Bandung’s planters and colonial elite had enjoyed wine, women and song at the Societeit Concordia, a fine establishment in the heart of the city that only admitted Preangerplanters (Dutch planters) and Europeans. In 1954, President Sukarno requisitioned the spacious club’s premises and ordered them to move out to the hills.

Thinking they were here to stay, the club engaged the city’s leading Dutch architect Gmelig Meyling and his firm NV Ingenieurs Bureau Vrijburg to design a statement clubhouse high up in the hills of Ciumbuleuit – far removed in style and expression from their vacated neo-classical pleasure palace.

The club was the perfect coda to Meyling’s creative last decade in Indonesia, which ended in early 1957. The clubhouse, his last project in Indonesia was a prelude to the mass expulsion and nationalisation of all Dutch assets. The renamed club and hotel is, however, open to the paying public; Ciumbuleuit has become the premier address in Bandung and Meyling’s former bureau trades as PT Sangkuriang. Over the decades – without a Sukarno figure – the non-aligned movement attempted several half-hearted comebacks. Russia, China and the US have reconvened a vintage form of geopolitics. This new form of tripolarity, however, shares the world stage with a hundred varieties of nationalism, thus making for uncertain times for today’s foreign experts based in Indonesia.

- The Bumi Sangkuriang 1956, Bandung

- Former planters bar, 1956 now the Bumi Sangkuriang, Bandung

Author

Tariq Khalil lives and works in Indonesia. His photographs—always about buildings and their histories—have been exhibited as solo and group shows in London, cities across the UK, Dubai, Jakarta, and Athens. For some seven years, Tariq has taken whatever opportunity has come his way to make Retronesia, which is currently available on Amazon only. It is his most ambitious project to date and has featured in Kompas, Indonesia’s national daily newspaper and the Sydney Morning Herald. Retronesia will be at the Ubud Writers Festival in October 2018. See more of Retronesia on Facebook and Instagram. Tariq Khalil can be contacted on sritariq@gmail.com

Tariq Khalil lives and works in Indonesia. His photographs—always about buildings and their histories—have been exhibited as solo and group shows in London, cities across the UK, Dubai, Jakarta, and Athens. For some seven years, Tariq has taken whatever opportunity has come his way to make Retronesia, which is currently available on Amazon only. It is his most ambitious project to date and has featured in Kompas, Indonesia’s national daily newspaper and the Sydney Morning Herald. Retronesia will be at the Ubud Writers Festival in October 2018. See more of Retronesia on Facebook and Instagram. Tariq Khalil can be contacted on sritariq@gmail.com

–

Comments

MODERN DUTCH ARCHITECTURE???

wowsie.

This requires a discussion that is better held face-to-face!

Other than that, the article is your typical, articulate, amusing, knowledge-through-adversity/adventure sojourn that you are SO very GOOD at.

On anecdotal level, Jenki architectural style was formed in the spirit of rebellious from the Dutch architecture. When Indonesia was gaining independence, all the dutch architects returned to their home country. What left behind was their Indonesian assistants, which might know a little about architecture, but wasn’t have a good grasp about the subject. These assistants then tried to design buildings without proper knowledge about it, and try to came out with a new style to differ themselves from the dutch architect. The result is buildings that were heavily influenced by Dutch aesthethic, but I would say awkward in execution and sometimes outrages in its proportions. This Jenki architecture style still could be found in many big cities in Indonesia, mostly in the form of old residential houses. For that reason I think it’s a little far-fetched to categories it as a modern dutch architecture. It’s eclectic at best.

On the other hand, I enjoy the photographs of the buildings in this article, as I always found architecture fascinating. The last building that he wrote about, Bumi Sangkuriang, is in Bandung. I just visited it yesterday for meeting. It’s a very beautiful complex. Unfortunately the owner now add some new garden and slides in the pool area, that are not very pleasing to see. The best addition was a renovation of the Concordia Hotel in the same complex. It was designed by one of Indonesia prominent architect, Mr. Tan Tjiang Ay. The newly renovated building looks very modern, but still respect the main Bumi Sangkuriang building and it’s surrounding.