- April Surgent, In the end it was the sea., 2017, cameo engraved glass, 15 × 22.75 × .75 inches

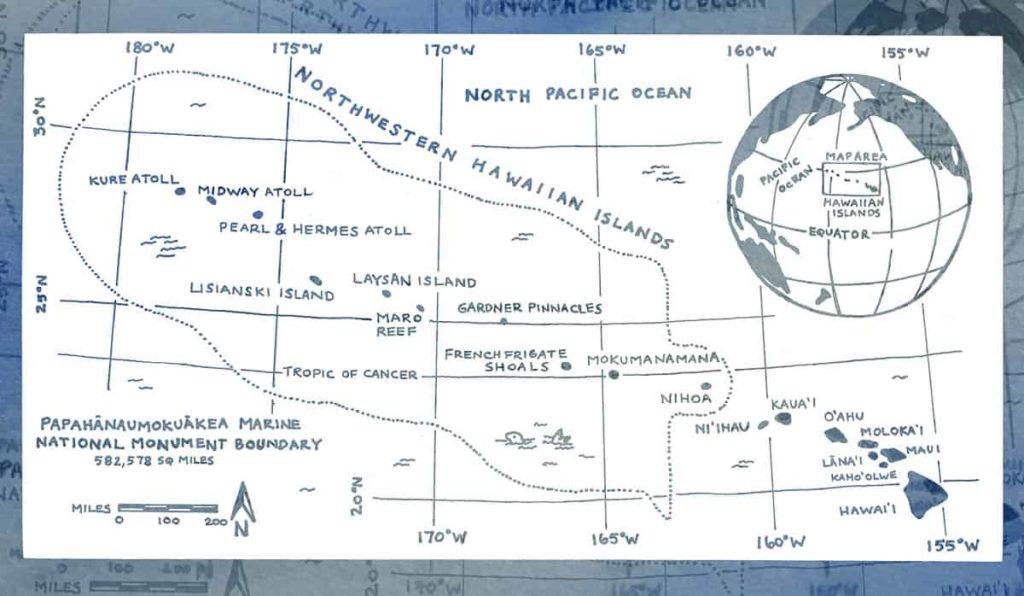

- The small, low-lying islands and islets of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument provide critical habitat for green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas / Honu) and Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi / ‘Ilio holo i ka uaua), who haul out on shore to rest.

- April Surgent, That dream, then, it was here, 2017, cameo engraved glass, 19.25 × 13 × .75 inches

- April Surgent, That dream, then, it was here (detail), 2017, cameo engraved glass, 19.25 × 13 × .75 inches

- April Surgent, The unnatural movement of the ocean with plastic, 2017, cameo engraved glass, 30 × 30 × .75 inches

- Onsite installation of disposable lighters on the shore of Southeast Island. All of the disposable lighters were found and collected throughout Pearl and Hermes Atoll (Manawai). Save for derelict fishing gear, the bulk of marine debris that washes ashore in the remote islands of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument are commonly used items, such as ‘disposable’ lighters.

- April Surgent, The astonishing afterlife of our disposable objects., 2017, cameo engraved glass, 25 × 25 × .75 inches

- April Surgent, The astonishing afterlife of our disposable objects (detail), 2017, cameo engraved glass, 25 × 25 × .75 inches

- April Surgent, Ubiquitously. Sea and sky wrapped around me. The solitude here, 2017, cameo engraved glass, 25 × 25 × .75 inches

- S. Youngstrom approaches brown noddies (Anous stolidus pileatus/Noio koha) while on patrol for Hawaiian monk seals.

- S. Youngstrom hauls a ghost net up the beach from the shoreline in an effort to reduce the threat of wildlife entanglement. Each year, the monk seal program deploys five field camps to the remote islands and atolls of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument that are accessible only by ship. The logistics are complex and the work is strenuous, requiring the generous dedication of dozens of intrepid souls.

- Buoys and floats litter the interior of Seal-Kittery Island. Derelict fishing gear is abundant in the Pearl and Hermes Atoll (Manawai).

- April Surgent, Self-portrait in personal tent

The story of the Hawaiian monk seal starts some 13 million years ago, when at some point these seals found the most remote chain of islands in the world — the islands that would one day be known as Hawaii. Hawaiian monk seals spent the majority of their lengthy tenure in Hawaii undisturbed, simply being monk seals. They foraged in stunningly blue tropical waters for fish and octopus, searching for food in the shallow coral reefs or down in the depths where the light of day cannot reach. They avoided the sharp teeth of their only predators: sharks. And each year, adult females gave birth to small, 20-pound, skinny, black pups that they nursed and defended for six weeks before leaving them to be on their own. This cycle repeated itself through the centuries, undisturbed and pure, until the day that man discovered the monk seals’ verdant isolated oasis.

It is estimated that the first Polynesians arrived in the Hawaiian Archipelago 800 years ago. Cultural and archaeological evidence indicates that monk seals disappeared from the main Hawaiian Islands (the high islands where people live and tourists flock to) relatively early in the islands’ settlement.

The monk seals found refuge in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, a group of small islands and atolls stretching over a 1,000 miles beyond the island of Kauai, until the second wave of humans arrived, heralded by Captain Cook’s discovery of Hawaii in 1778. Seals were hunted for food and oil, were disturbed from their breeding habitat, and faced other insults that would bring them to the brink of extinction multiple times. By the late 1970s, the population was a fraction of its peak numbers: monk seals were listed as endangered in 1976 under the US Endangered Species Act. This would begin the new age of monk seal research and conservation efforts by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, and their partners.

Over the decades, NOAA’s monk seal research teams evolved. The early, rag-tag group of biologists started by taking on the Herculean task of understanding the seals’ basic biology, ecology, and population trends, and then they began developing plans for recovery. NOAA’s monk seal program became one of the most proactive conservation programs on the planet. New innovations and conservation activities were introduced and the monk seal population decline slowed dramatically.

In the late 1990’s, there was another development, largely unforeseen by scientists but critical for monk seal recovery: monk seals returned to the main Hawaiian Islands. Given the level of human presence and disturbance, it seemed an impossibility that the seals would ever achieve a foothold, much less significantly recolonize the main islands. As is often the case, however, we underestimated nature’s resilience and she proved us wrong. Today, 300 seals—or roughly one-fifth of the monk seal population—lives along the shores of our main eight Hawaiian Islands. With this community of seals came a host of new issues for monk seal conservation, primarily in the form of human-to-seal contact.

Monk seals had been missing from the main Hawaiian Islands for centuries and generations of people had been born and raised without ever being aware of the existence of monk seals. So it is understandable that with the arrival of the seal came conflict and concerns. Residents and tourists alike had no idea how important rest was to a monk seal’s survival. When a monk seal would haul out of the water for a snooze on a popular beach, instead of keeping their distance, curious humans would approach for photos or to try to feed them, causing the monk seal to retreat back into the water. Fishermen, many of whom rely on their catch to feed their families, were concerned that this new arrival would consume the remainder of an already dwindling and overtaxed food resource. The monk seal conservation program suddenly had a new element to its mission: human-versus-seal conflict. The work could no longer be just about studying and saving monk seals. Instead, a full-on engagement with communities was necessary to increase awareness of the seal, rally the public to support the species, and build a culture of coexistence between man and monk seal.

While the NOAA program excelled in our science and conservation work, we initially struggled with connecting with the public. Our first successes in piquing the public’s interest and starting a groundswell of support for monk seal conservation were through traditional means such as nature documentaries. The most impactful of these was our work with National

Geographic, using their seal-mounted cameras (or, Crittercams) to reveal the underwater secrets of the monk seal. The value to science was massive; the value to raising awareness was immeasurable. But despite this work, we knew there was more to be done, more people to connect with, and a variety of arts and media we could tap into to touch people’s hearts and minds.

It was at this time I thought of emulating the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program, a program designed to tap into the arts and humanities to increase understanding of the Antarctic and help document America’s Antarctic heritage. I put out feelers to colleagues to look for an artist who might be interested in a project with the monk seal program. I didn’t have to wait long. I was excited when April Surgent first contacted me, as she seemed like a godsend: she had been endorsed by one of our most trusted field biologists and she had experience working in a remote field station in Antarctica. I had one simple and non-negotiable request of April. If she wanted to tell the story of our program or the seals we are fighting for, then she had to live the experience. It couldn’t just be a few days of field work on Oahu’s crowded beaches, or even a 2-3 week research cruise in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. April would have to commit herself to becoming one of our field biologists. She was going to have to immerse herself into a three to four-month field camp and do all the work our other biologists would do. That would include learning to catch and handle seals, collecting and entering data, intervening to help seals, and more. She would have to experience all the highs and lows of field work. I wanted her to experience growing so close to the animals you work with that you can identify them just by the patchwork of scars and birthmarks in their fur, becoming connected to them all the while knowing that some would be lost. I wanted her to be awestruck by the beautiful sunrises and sunsets that reveal an atoll that seems to hold every shade of blue imaginable, while scratching the seemingly never-ending itch of tick bites. I wanted her to fall asleep to the sound of trade-winds blowing through camp, punctuated by the occasional seal snore after scraping bird poop off her pillow. I thought it was important that she understand the highs and lows of conservation and the sacrifices our field teams make each year as they commit to live on a remote island. I wanted these experiences to contribute to the way April viewed our mission so that she could infuse that experience—that truth—into her art.

Without hesitation, April took that challenge and committed fully to being part of our team. She learned how to drive a small boat in a complex coral reef, how to give an IV drip to a sick campmate, how to safely handle and tag a young monk seal, how to conduct a necropsy, and more. In some ways, her workload was double that of the other staff, since every day she worked on her art as well, capturing the impressions this strange new existence made upon her. In all ways, April rose to the challenge. She worked with her team to overcome adversity (something always goes wrong in complicated field camps) and thrived through the season, conducting science and saving seals. She earned the right to call herself a conservation scientist.

Today, as you read this or walk through the gallery, it is about the art — not the science — of monk seal conservation. I hope you get a greater sense, and maybe appreciation, of the humanity behind the efforts to save this species.

I hope you are moved by pieces that demonstrate the impact that our plastic addiction has on the natural world, even the world’s most remote island chain. And I hope you are moved to become part of finding a better way forward for the future.

As I write this, the monk seal population is at 1,400 — up from 1,100 seals a few years ago. We’ve had three years of positive growth. After roughly 60 years of decline that is a reason to celebrate. We also have an intensive conservation program that is making a difference for the seals: roughly 30% of the population is alive today because of our recovery efforts. But what gives me the most hope is the continued growth of our monk seal ‘ohana — our family — the group of government agencies, private groups, volunteers, and others that have joined our efforts to save seals. These new relationships, like this collaboration with April, allow us to share our story with people far beyond the shores of Hawaii and rally them to our cause. So while some of these works will show the hardships of conservation and humans’ impacts on nature, remember, there is much to be hopeful for.

All photographs are taken under the authority of and in accordance to NMFS Permit No.16632-01 and PMNM-2016-011

Author

Charles Littnan is lead scientist, Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program NOAA Fisheries

Charles Littnan is lead scientist, Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program NOAA Fisheries