- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Acción Machasa

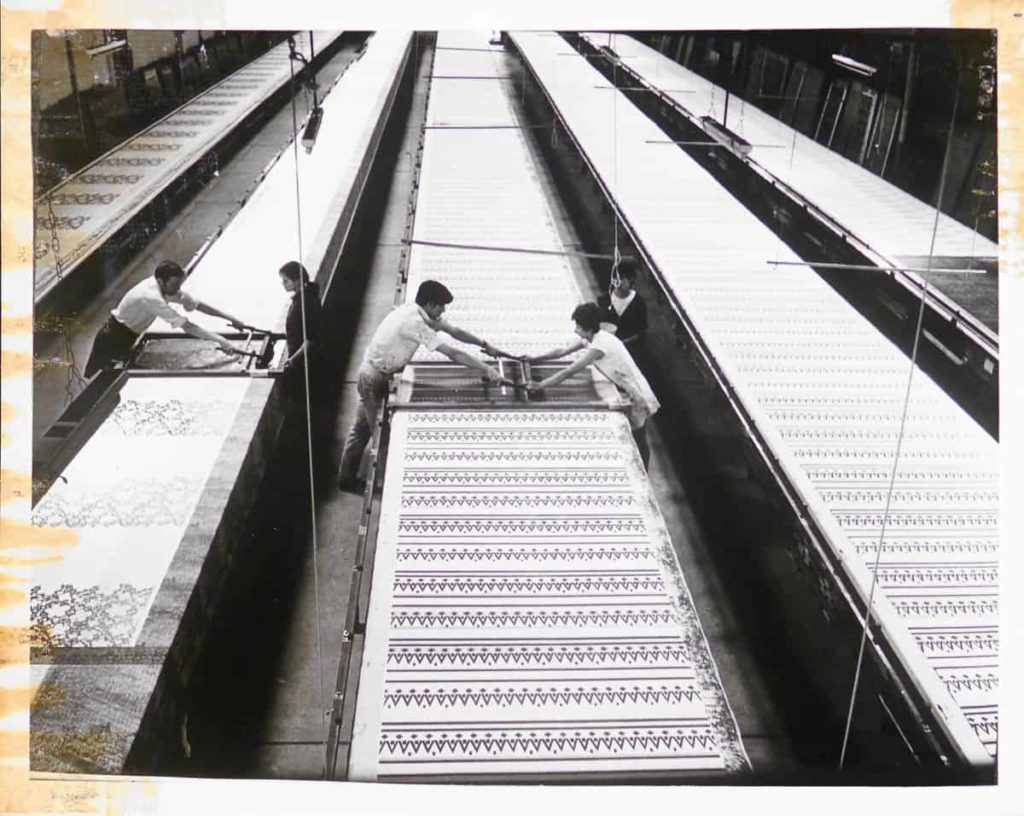

- Artisanal print Factory Alejandro Stuven, Santiago, Chile, photography courtesy of Stuven family

- Quality check at the final stage of production. Oveja Tomé textile factory, Tomé, Chile. Circa 1960. Photo courtesy Ministry of Education, Educar Chile programme, provided by the University of Chile

I am a Chilean textile artist, my country is the southernmost one in South America; working and living in the capital and largest city, Santiago, my time is shared between creating works of art and lecturing in the Textile Arts Workshop at the Fine Arts School of the University of Chile.

I spent my childhood in the eighties, under a military dictatorship, with nightly curfews and frequent “cacerolazos” – neighbours gathering on their doorsteps at a spontaneously agreed moment, hitting pots and pans – as a way of voicing a social protest otherwise repressed by the military junta.

My recollections as a little girl are a strange mixture of fear and emotion, living in a divided and polarised country, but at the same time witnessing a level of solidarity that I have never seen again. The social fabric was still intact and allowed us to keep going. Next door lived a medical doctor, another neighbour was a seamstress, whoever happened to have a phone or a washing machine shared with the rest, even if those were times of few gadgets and certainly material scarcity, people were ready to help each other.

Within this sociopolitical context my life was taking shape, influenced by a historian mother that loves books and written memory, a lawyer father working in an office under what for me was a boring routine, who taught me by words and deeds the concepts of justice, fairness and equity; a grandmother with some Christian Arab ancestors that fled the oppressive conditions of the Ottoman Empire, deserves special mention. She had full command of the arts of weaving and sewing, from her I learned and got to love this trade, looking at her dexterity to fix old clothes and how our furniture upholstery was miraculously transformed at the pace of a small sewing machine. My family memories were treasured as each piece of clothing was repaired, a time when nothing was abundant, except love and idealism.

All these traits are a legacy conditioning the search for subjects through which my artistic expression is channelled, focusing especially into that period in the history of my country when the common people felt that they had a place in the effort to build their dreams.

Later on, when time came to get academic training in the fine arts, it was all but natural to choose textile art. Textile tradition, trade and manual abilities became my artistic language, “textility” – if you allow me a word not found in dictionaries – was an important element in my personal experience and also in the recent history of my own country.

Textiles showed up everywhere, whether I looked into native peoples’ heritage expressed in wonderful textile pieces or looking at the contemporary works such as Alejandro Stuvens artisanal printed fabrics. Weaving, spinning, dyeing and printing made sense and became a liberating experience that should be nurtured and developed, including both the techniques and the history related to them.

From such starting point and within the framework of my Master´s thesis, I carried out the research that became The Factories Project, including Machasa Action and The Last Metres, as well as other components that are still works in progress. The Project is focused upon the history of the main textile factories in Chile and their relationship with the social and political events of the 1970´s, the Popular Unity government and the 1973 military coup and its aftermath.

Although the factories were established in the nineteen-thirties and had gained a solid position among the main industries in the country, it was only in the seventies that they became a stalwart of social advance; textile workers triggered more social and political reforms than any other sector of the economy. Previous labour demands such as eight hour working days or paid vacation time were topped by nationalisation. Workers felt that such measure made them owners of their source of employment and gave labourers a leading role in the advance of the country into socialism.

To a large extent, the social cohesion and shared vision of the labourers were facilitated by the fact that the two most important textile industries (Yarur and Sumar) had built a sort of company towns, albeit right in the country´s main city. This permanent interaction between workers and families, plus the location in the middle of a large city, gave rise to a particular type of identity, merging place, trade and family life.

One of the factories, Yarur (later operating as Machasa) had outgrown the original facilities into neighbouring buildings across the street. In order to facilitate operations and avoid the intense traffic at street level, the different sections of the industry were connected by underground tunnels, for instance, dyeing was carried out in a different building away from the looms. There was a rhythmic movement of raw, partially elaborated and finished materials along this network, colourless fabrics went through the tunnels and came back vividly printed. I imagined these interior corridors as a subterranean fabric of dialogues and personal histories that, once articulated, would change peoples’ lives and that of the place. That same tunnel would turn later into the escape route for the few trade unionists that saved their lives after the military coup and the following repression of all dissenting opponents.

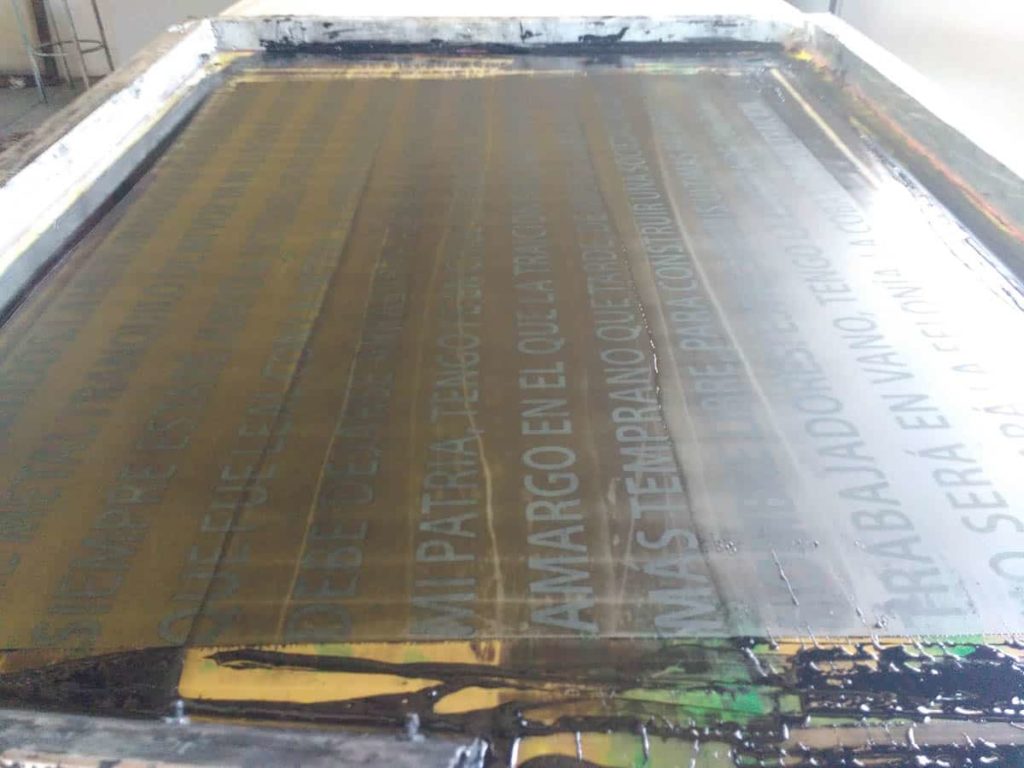

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann serigraphy fabric process

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann serigraphy fabric process

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann serigraphy fabric process

Acción Machasa aims to make visible some physical and symbolic invisibilities; by marking at street level the exact place where the tunnel crosses under the street the invisible tunnel underneath is made visible in the pavement, this was achieved by repeatedly dragging a blue dyed 28 kilo bundle of spun cotton across the street until the mark was clearly visible. At the same time, the blue area commemorates the particular stories of nameless people, their thoughts, movements, work assignments and everything related to their lives.

After the military coup all nationalized factories were given back to the original owners or sold at ridiculous prices, labour unions were banned and most workers fired. Ironically, the bonanza for the owners did not last long, the new economic policies imposed by the dictatorship opened the way for massive imports assisted by the undervaluation of foreign currencies, as a result, the factories soon went broke. No one supported the businessmen, all the voices that could have helped them had been suppressed by force, the social network that in other circumstances might have saved them had been destroyed. The demise of the factories also shattered the workers’ dream of living by the practice of their trade in a fair and sympathetic society. The social utopia where the common people were at the centre of the stage fell with the government of president Salvador Allende, but the ensuing destruction of most industries was a double defeat.

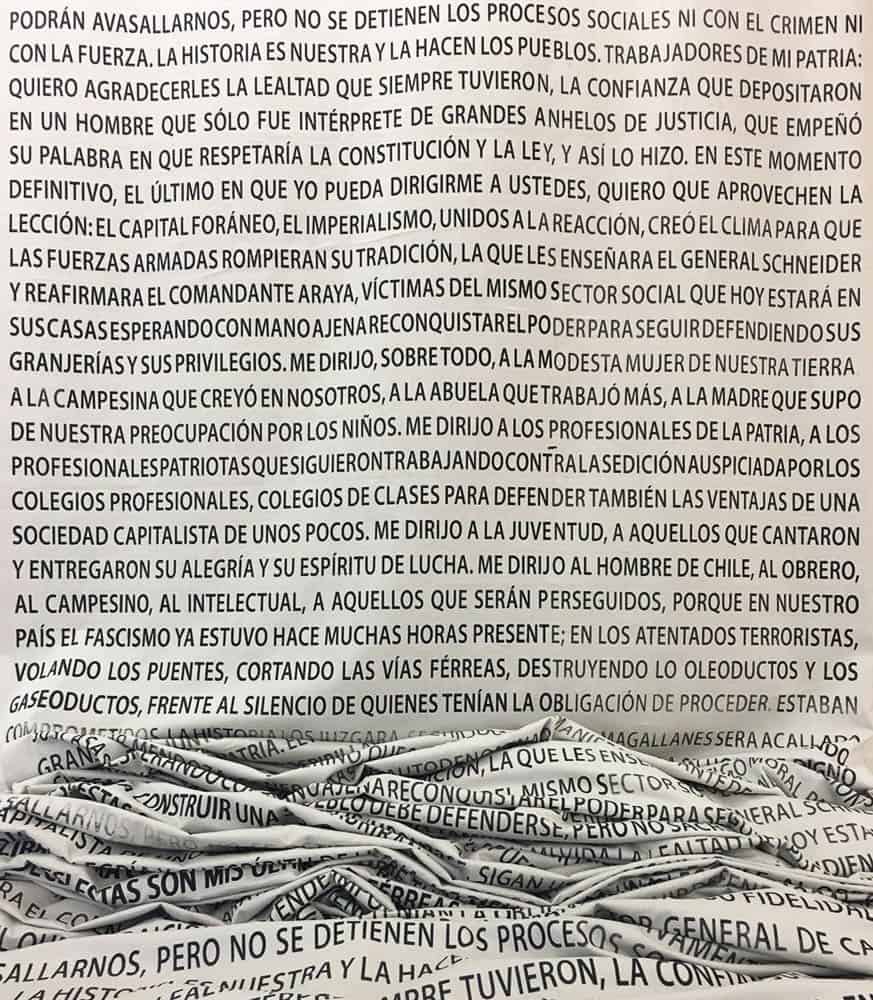

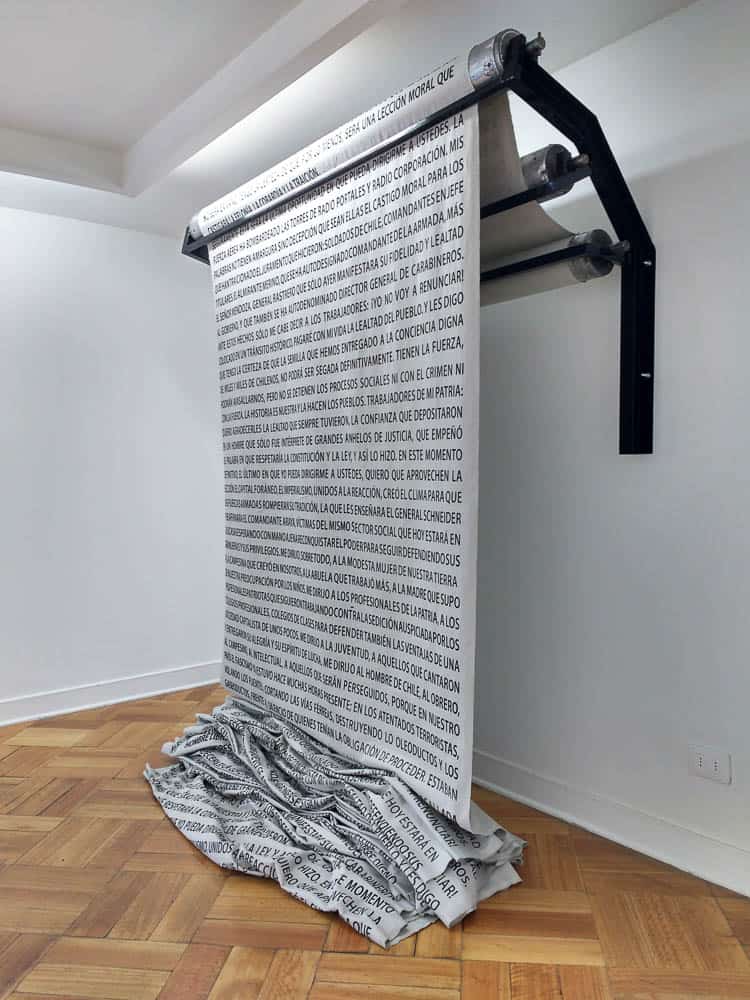

Acción Machasa focused in the bottom-up construction of a society by the common people, The Last Metres is inspired in a different viewpoint, the latter looks into the close relationship between the Popular Unity government – on top – and the working class. A structure supports a 40 metres long roll of fabric, the final speech of president Allende was manually printed in the roll. The speech was aired through the last radio station not yet captured by the army, while Government House was under attack by the military, minutes before the president’s death. The artwork alludes to the last speech of a democratically elected leader and at the same time to the last metres of fabric that a once-thriving industry was about to produce. The looms output is memory and history.

The military dictatorship lasted for 17 years. During this period people became divided, repression was harsh against any dissenting voice and a different economic system – lasting until now – was forcibly thrust upon the population. A way of living and establishing social relationships, with their particular times and rhythms, was forcibly terminated – eliminating the attending cultural expressions and identities.

Therefore, my work traces the thread between textiles and memory, in order to recover a fragment of history allowing people – through art – to rescue from obscurity such testimonies from our recent past, in the hope that such actions will help us to pursue the construction of a better society.

Author

I live in Santiago, Chile, and teach textile arts at the Department of Fine Arts, College of Arts, University of Chile. I am also in my final year of a Master’s degree in Fine Arts. Las Fábricas (The Factories) is my graduation project for the degree, including a written text and a number of visual art pieces, among them Machasa Action and The Last Metres.

I live in Santiago, Chile, and teach textile arts at the Department of Fine Arts, College of Arts, University of Chile. I am also in my final year of a Master’s degree in Fine Arts. Las Fábricas (The Factories) is my graduation project for the degree, including a written text and a number of visual art pieces, among them Machasa Action and The Last Metres.

Postscript

The Last Metres was funded by the Master of Fine Arts Programme of the University of Chile. A small and very helpful textile workshop, Siena Tapices Naturales, provided the metal frameworks and wooden poles that made possible to put together the whole work of art.

The 40 metres long fabric for The Last Metres was manually printed using only serigraphy techniques. The process was challenging and required precision and speed. Given the length of the speech and the characteristics of the printing method, the work proceeded by segments, using eight serigraphy frames containing the text of the speech, printed over ten times along the fabric. The most difficult task was the adjustment and alignment of each consecutive fragment, compounded by the need to proceed as fast as possible because the ink dried very quickly at the ambient temperature of the shop, seriously limiting our printing runs. The four members of the working team achieved a high degree of coordination in aligning, inking and stretching the fabric, in order to proceed without soiling it. In the end, we succeeded!

The Last Metres was shown in the D21 Art Gallery in Santiago, within an art exhibition called Progress curated by Professor Gonzalo Díaz, National Prize of the Arts. The show included pieces by graduate students of the College.

The Factories Project is the base of my research for the Master’s degree, to be finished by December 2018. The whole work, including each and every step, is scheduled to be shown in January 2019 at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago, Chile.

The show will include work that is still in progress, narrating life and working pace in the factory. Although still unfinished and subject to changes, I can say in advance that the pieces are woven images that reproduce, using tapestry techniques, brief overviews of the documentary A Happy Summer, filmed during the Popular Unity government, which promoted a scheme of Spas for the Common People. Part of the documentary was filmed in one of the nationalized textile factories and is very important to me because it presents real images about the rhythm of life in the factory, showing the yearnings and struggles of the times.