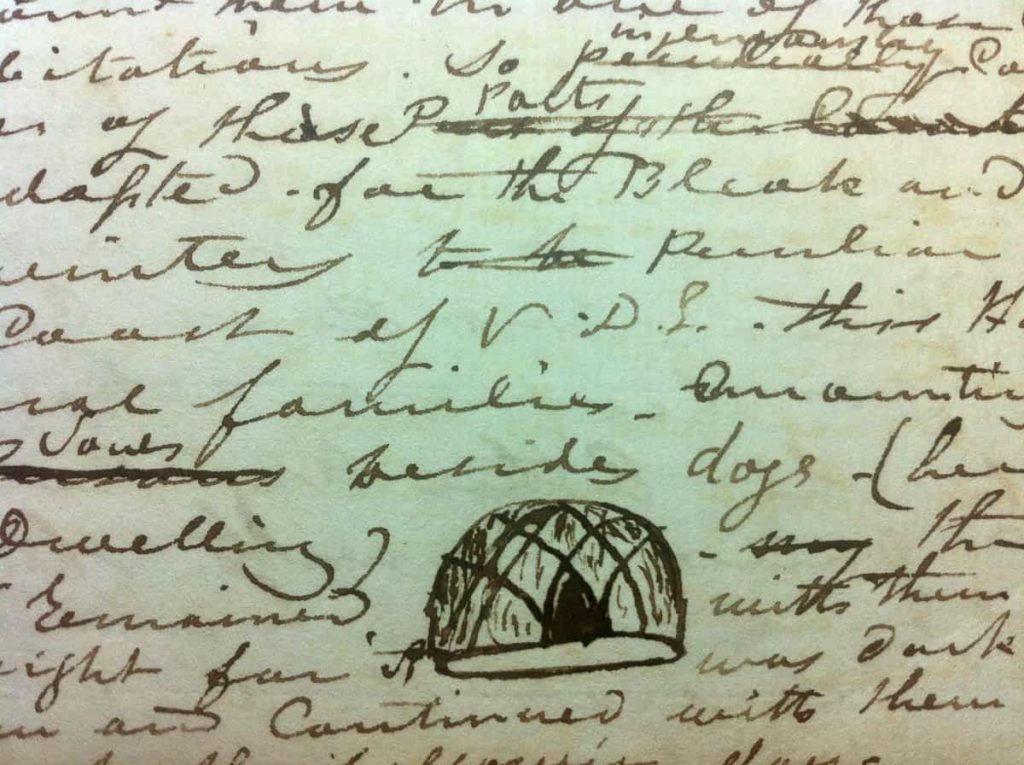

Nestled between the lines of poorly-written script in a small, battered journal dated February 13, 1832 is a crude diagram. No larger than a thumbnail, it is the sum total record of the architectural engineering practice of a people who were swept from their homelands within a lifetime of the arrival of the British on the island of Tasmania. The identity of the journalist is not important to this story. Plenty had been written about him already. Indeed, it is too often the case that the writers of colonial records become pre-eminent in the accounting of cultures in which they had no part. Or worse, the account of their part in the undoing of a culture becomes entangled, and mistaken for a description of the culture itself. This is how our knowledge of a people is colonised by history.

The last custodian of palawa (Tasmanian Aboriginal) architectural knowledge probably died sometime in the late eighteenth or very early nineteenth centuries. Unlike the practices of shell necklace making, which were passed down through the more resilient culture of Aboriginal women, architecture seemed to slip away, as the men who carried this responsibility were distracted from their art by the business of war. The advancing colonial frontier brought with it attacks by settlers, making villages of fixed dwellings no longer safe. In June 1804, the year of commencement of British invasion, Lieutenant-Governor Collins reported a native village on the Huon River that was home to twenty families. At Little Sandy Bay, not far from Hobart Town, there was a large village called kreewer. By the time the journal entry was made, villages like these close to British outposts had all been destroyed. The only ones remaining were in the remote highlands and west coast. It seems odd that, over a period of thirty years, only one person bothered to sketch their design.

When I started work on the development of a new Indigenous gallery at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMAG) in Launceston in 2015, there were already two small replica Aboriginal huts. One of these was in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s ningina tunapri gallery. The other, at the tiagarra cultural centre in Devonport. I had known these structures for years; taking many visitors to see them as an insight into the lives of my ancestors. They were known as linene by the nations of the south east, and gardown by the people of the west. But these examples had always left me feeling unsatisfied. Thatched with bark, and loosely corresponding to the few written descriptions of a “dome-like” or “beehive” shape, there was nevertheless something awkward about their structure. They lacked the elegance so characteristic of designs conceived and refined over millennia. My eye and my heart wanted more.

David Gough, a skilled spear maker and cultural educator, had been managing tiagarra for the past few years. He was also the co-chair of the QVMAG Aboriginal Reference Group. We agreed that there was more to be done. David was familiar with the qualities of the long, thin poles of dogwood and tea tree from which spears were made. These had also been used—bent over to form radiating arches—for making the two existing linene. We had been researching the colonial records and were certain that bark thatch might be correct for the lightly-built windbreaks of the east coast, but it was grass that was more properly used for the larger, circular huts that we wanted to recreate. On a visit to the Mitchell Library in Sydney, I had been searching their colonial records of early Tasmania and found the small sketches of gardown recorded from the west coast. One of these sketches confirmed the use of grass thatch. The other was much more exciting. It magically revealed the internal structure of the building. The arched ribs were not radial as had been thought before. Rather than meeting at the apex, they were much more sophisticated. Like the dome of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, the crossed arches intertwined to form polygons.

The QVMAG gallery designer Andrew Johnson, who we were working closely with, constructed a model to guide our next steps. It was immediately apparent that the structural strength of this gridshell design was superior to the earlier approaches. The interwoven, crossed arches had both lateral and torsional rigidity far-greater than the radial model. We knew immediately that we had re-discovered the elegant truth of palawa engineering. A small sketch, reclaimed from the scrawled pages of an 1832 journal, had returned to life.

Our vision for the overall gallery design had been inspired, from the very beginning, by the towering, cross-hatched forms of the tea tree forest. These provided sheltering environments for palawa people for a thousand generations, and continue to be places of inspiration and refuge for Tasmanian Aboriginal people today. In realising the architectural design integrity of traditional palawa buildings, we had uncovered a harmonious inter-relation of form that acknowledged the slender tea tree stems as resources for spear-making, and for the architectural frames of our traditional buildings. But more importantly, we had reclaimed cultural knowledge from a history that had previously served as a record of loss; re-enlivening cultural knowledge and practice, and de-colonising a story of forfeiture into one of renewal.

Linene, (Tasmanian Aboriginal Hut), 2017, David Gough and Greg Lehman. The Gallery of First Tasmanians, QVMAG, Launceston

Author

Greg Lehman is an art historian, essayist and curator. He is descended from the Trawulwuy nation of north-east Tasmania, as well as Irish and German immigrants to Australia. Greg has been writing and researching issues of engagement with Aboriginal art, culture and heritage for over thirty years. He recently co-curated The National Picture: the art of Tasmania’s Black War, at the National Gallery of Australia and co-wrote the libretto for A Tasmanian Requiem, an oratorio for voice and brass.

Greg Lehman is an art historian, essayist and curator. He is descended from the Trawulwuy nation of north-east Tasmania, as well as Irish and German immigrants to Australia. Greg has been writing and researching issues of engagement with Aboriginal art, culture and heritage for over thirty years. He recently co-curated The National Picture: the art of Tasmania’s Black War, at the National Gallery of Australia and co-wrote the libretto for A Tasmanian Requiem, an oratorio for voice and brass.