Inspired by writers like Edmund de Waal, D Wood argues for the importance of craft writing, by makers.

Edmund de Waal, the renowned ceramic artist, is also a writer. He states that his first book, The Hare with Amber Eyes, “changed my life.” At the same time as preparing an installation of 425 porcelain vessels for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2009, he had to submit the draft for the book. In a Guardian article in 2020, he said:

[E]very night I would be writing the last chapters about how close memoir feels to trespass, how to navigate what to say and what to leave unsaid …. We were firing the kilns every day. There were stacks of books among the glaze tests.

de Waal says that after the launch of The Hare with Amber Eyes, which traces the history of a collection of Japanese netsuke owned by his ancestors, he thought he would be able to go back to making. But he was overwhelmed by the thousands of letters that his book generated. The story of the tiny handmade objects and their owners had resonance with readers for a wide variety of reasons. And while one reviewer1.Laura Miller, Review: “The White Road,‘ by Edmund de Waal,” New York Times (Online), New York: New York Times Company. Dec 10, 2015. said the book was more about the colourful wealthy characters who collected and preserved the netsukes, I would argue that the objects and their human connections, written about by a maker, were what inspired the memories of readers and fostered the book’s success.

de Waal’s second book, The White Road: Journey into an Obsession, follows his travels to Jingdezhen, China; Dresden, Germany; the Appalachian Mountains of South Carolina; and Devon, England, in pursuit of the pursuit of porcelain. The White Road is a must-read for students of ceramics, not only for its account of the discovery of ingredients for porcelain in geologically-rich locations, but also because it is a manifestation of the need for writing about one’s craft. de Waal describes his position:

[It’s been] a decade or so of talking up why things matter and why it is good to make … Five hard years or so on why objects need histories, and why artists and makers need to write, to artists and makers who don’t believe me and just wish someone else would do it for them.2.Edmund de Waal, The White Road: Journey into an Obsession (Toronto, Knopf: 2015), 93.

Quite rightly, Edmund de Waal doesn’t want to be the only proselytizer about the need for craft writing. So this presentation addresses why craft practitioners need to stop wishing that someone else will do the writing for them.

Craft and writing

It’s not as if craft practitioners can’t or don’t write. Ralph Caplan, the 2005 writer in residence at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine, stated that they do in unexpected ways:

For her basket workshop, Lissa Hunter distributed excerpts of advice on writing from Annie Dillard’s essay, “Write ‘til You Drop.” In the book arts workshop … words were raw material, and Carol Barton kept a playful focus on them, even when teaching the structural technicalities of paper engineering….and Peter Pierobon began his [woodworking] workshop by asking everyone in it to make a list of adjectives that were important to them. … What the students wrote helped uncover what they wanted most deeply to do… 3.Ralph Caplan, “Making More Than Sense,” The Haystack Reader: Collected Essays on Craft, 1991-2009 (Orono, ME: U of Maine Press, 2010), 331-344, p. 335.

Craft students and practitioners, usually under duress, write artist statements, grant applications and catalogue blurbs; they give presentations about their work, and try to sell what they make by means that require grammar, spelling and erudition. And, with craft, design or art history being part of the curriculum at undergraduate and graduate levels of education, essays about the Arts and Crafts Movement, the Shakers, Liz Williamson and Kevin Perkins have certainly been written.

Yet, this is not what I’m talking about. Garth Clark, writer and commentator on modern and contemporary ceramic art and the craft movement, concluded a controversial 2008 article, “How Envy Killed the Crafts,” with this statement: “the legacy … rests on how successfully and intelligently the craft community completes the scholarship.”4.Garth Clark, “How Envy Killed the Crafts,” in Glenn Adamson, ed., The Craft Reader (London: Berg, 2018), 445-453, p. 452- 453. I’ve taken Clark’s comments slightly out of context in that he was referring to what he felt was the “golden period” of craft from 1945 to 1980. But they align with what the editors of the Journal of Modern Craft stated in the first edition, also published in 2008: “[Craft] is, after all, barely developed as an area of scholarly research. At the time of writing there are no departments of craft studies and only a handful of academic positions in the study of craft history or theory.”5.Editorial introduction, Journal of Modern Craft, 1(1) (March 2008): 5.

Craft has had a resurgence since Clark’s comments over a decade ago. The JMC’s editors re-viewed the state of craft in 2017, and painted a rosier picture:

Academic appointments are still few and far between, relative to art and design history, but the number of scholars specializing in the history and theory of craft has nonetheless multiplied in the past decade, and curatorial positions in the field have also grown in number.6.Journal Editors, “Modern Craft Studies: The Decade in Review,” Journal of Modern Craft, 10(1) (March 2017): 5- 18, p. 6

This editorial was hagiographic in lauding the JMC’s contributions to craft scholarship alongside those of one of its founding editors, Glenn Adamson. Yet part of the reason that the field still needs craft scholarship is precisely because of the predominance of a few voices and points of view like those of Adamson.

In observing the credentials of many of the scholars writing about craft today, I note that they are art and humanities historians, who have never … made …. anything. The craft canon welcomes dissertations, book chapters and journal articles about craft from anthropology, social geography, material studies, philosophy and feminist studies but where are the craft practitioners who can write passionately and knowledgeably about processes, techniques, traditions and lifestyle? My own PhD, about studio furniture makers and the craft movement in New Zealand, was greatly enhanced by my being able to talk to makers as a craftsperson.

Why not let the art historians do the critical writing about craft? Bruce Metcalf, a jeweller and writer, has asserted:

[M]y sense is that craft must be conceived not as a subset of fine art, but as a distinct field of both practice and study. In my view, craft is related to both art and design – and overlaps portions of both – but is distinct enough to merit being a field unto itself.

Metcalf was forthright in addressing a craft symposium in Toronto in 1999:

Many observers of contemporary craft have suggested that art and craft have merged or should merge. Implicit in such assertions is that, philosophically, craft as we know it and art as we know it are the same thing.7.Bruce Metcalf, Contemporary Craft: A Brief Overview,” in Jean Johnson, ED., Exploring Contemporary Craft: History, Theory and Critical Writing. (Toronto: Coach House Books & Harbourfront Centre, 2002), 13-23, p. 22.

He goes on to say that craft and art are NOT the same, with the result that craft history and art history, craft education and art education, and craft theory and art theory are not the same. Ergo: craft writers and art writers are not the same.

Signs of change

Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina, inaugurated a Master’s in Critical Craft Studies in 2018, the first program in North America. The website states:

Students investigate research methods from archives to oral histories … modes of presenting craft from street fairs to museum exhibitions, forms of writing … from exhibition reviews to academic journal articles, and alternative forms of documenting and communicating history, such as podcasts, symposia, online platforms, and curricular development.10

The evidence of the value of this curriculum was seen in CraftWays, an online symposium in July 2021, that included graduates of and candidates in the program. Amy Meissner, a textile artist, gave a presentation entitled ‘Engaging in the Craft of Repair’ for which she provided historical background from the Inuit in Alaska before leading a workshop in mending a sock; and Heather Powers, also a fibers practitioner, whose research was initially based on visits to artists’ studios, had to abandon that due to the pandemic and undertook a content analysis of studios featured in craft magazines. The latter is an example of the extrapolation of the embodied knowledge of her own studio to what she saw in two dimensions.

Also significant about the Warren Wilson program is that its Director, Namita Gupta Wiggers, is a BIPOC American. The craft community, until very recently, could be characterized as almost totally and completely dominated by “middle and upper crust whites.”8.Anthea Black and Nicole Burisch, eds. The New Politics of the Handmade: Craft, Art and Design, (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021) (p. 250, Figure 17.1). This quotation from 1972 by Allen Fannin (a Brooklyn weaver) comes from a letter to Francis Merritt (then director of Haystack) in which Fannin responds to Merritt’s request for assistance in attracting African-American instructors and students. Forty years later Wiggers echoed Fannin’s assertion: “Craft … continues to need—a range of voices to convey the breadth and depth of the field, to extend the work of leaders in past generations who stubbornly refused to let it disappear from view.” As a craft leader from a visible minority Wiggers is instilling the overdue: craft needs “diversity and difference.”

Garland is contributing to craft’s diversification and acknowledging the craft practices in countries that are usually absent from the craft canon. In 2015, prior to launching Garland, Kevin Murray reported the results of a survey about what Australian crafts practitioners wanted in a magazine. The response indicated “strong support for reflective writing, including reviews, essays and profiles” as well as craft histories. Instead of commercial promotion readers preferred “investigative, analytical, witty editorial inquiry … true, critical journalism, critiquing.” These desires, however, hark back to Edmund de Waal’s experience of practitioners wanting someone else to do the writing. Murray has been ardent in his efforts to attract a range of diverse authors for Garland. Many would not otherwise have a platform and I would suggest that in order to be a writer, just like being a craftsperson, practice is needed. Garland would be a respected venue in which to begin.

Murray addressed the topic of writing about craft in his essay, “Knowledge work in service of the crafts.” He refers to “journalists, curators, academics and online ‘content creators’” as knowledge workers. I agree with his belief that knowledge workers don’t HAVE to be makers, but would contend that in the crafts too few are makers. The result is that craft is not being written about by its own people. Murray puts forward three principles for knowledge workers: championing the uniqueness of craft instead of maintaining its negatives like being from the past, slow, inefficient and unscalable; legitimizing the insight gained through making by contact directly with craftspeople; and maintenance of perspective on the field so that issues like gender, race and class are given constructive criticism with the aim of improving and advancing the craft community. The art world is not going to advocate for craft; the design world is not going to legitimize making. We – the craft community – must do it ourselves.

Craft scholarship and sustain-ability

Australia has in its midst one of the world’s foremost critics about design and how design, in its many manifestations, degrades or defutures the social, technical and biological ecologies required for human existence. If anyone who is listening has not heard of Tony Fry, shame on you! In light of the inadequate outcome of COP26 in achieving consensus on actions to ameliorate climate change, it is relevant to invoke Fry. Politicians, bureaucrats and business leaders are not going to change the trajectory of the planet. The responsibility is being taken on by Fry and a growing number of others who care.

Fry contends that “craft knowledge is in fact of central importance to the future.”9.Tony Fry, ‘Sacred Design I: A Re-creational Theory,’ in Discovering Design: Explorations in Design Studies, ed. Richard Buchanan and Victor Margolin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995): 190-218, 212.

This knowledge will be conveyed by the perpetuation of craft skills, use of hand tools and familiarity with materials – that is, the teaching of the physical process of handmaking. In addition, it requires the expansion of writing about craft knowledge. Matthew Kiem, extending Fry’s views, states:

In being both directional and political craft contains the power to either prolong or transform conditions we acknowledge are unjust and damaging to the health and flourishing of human and non-human others…. It follows that in order for craft to become a transformative force, practitioners must develop a critically informed, practice-based commitment to assert the sustaining value within craft. 10.Matthew Kiem, “Theorising a Transformative Agenda for Craft,” craft + design enquiry (2011): 33–48, 34-35. 18 Metcalf, “Craft Education.”

Kiem reminds us that the onus is on craft and its practitioners. Period.

If the Scott Morrisons (current Australian Prime Minister) of this world continue to hold sway, the globe inherited by imminent generations will be severely compromised. In this worst-case scenario, humans equipped with knowledge of materials, non-power tools and techniques of making will be the survivors. This dystopian view provides justification for the maintenance of craft education programs. In order to prevent the dystopian outcome, craft needs writers who understand and promote the practice of handcraft. Quoting Bruce Metcalf again: “If craft has any hope at all of asserting its position in either the liberal arts or the visual arts” – and I would add the well-being of humankind – “it must claim its own identity, its own competence, its own educational methods, its own history, and its own forms.”

Epilogue

On the first day of my second year of craft studies, I was hit by a car that almost destroyed my left knee. The doctors said I could no longer consider activities that required standing for long periods. Up to this point, I was an above-average writer but insisted that I wanted to make rather than write. The accident put paid to being a craft practitioner in the medium I had chosen, woodworking. I completed my education, with limitations, but my writing was encouraged and received commendations; my first article was accepted for publication while I was a graduate student in furniture.

Life frequently intervenes in best-laid plans. Craft practice could be curtailed for many reasons yet the passion for craft need not be abandoned. I have been a dedicated writer for all craft media for 21 years, meeting artists and viewing exhibitions that were inspiring and changed lives. I encourage teachers and individuals to promote writing about craft as part-time or full-time support for this unique and essential form of making.

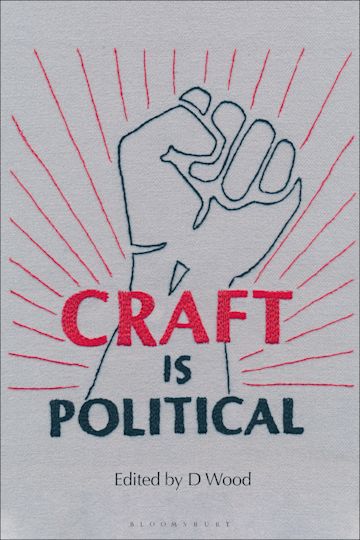

About D Wood

D Wood earned a Diploma in Crafts and Design in Canada and an MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design (2000). Her PhD addressed studio furniture and the contemporary craft movement in New Zealand. D has given presentations at international conferences and published extensively. She edited and contributed to Craft is Political (Bloomsbury 2021).

D Wood earned a Diploma in Crafts and Design in Canada and an MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design (2000). Her PhD addressed studio furniture and the contemporary craft movement in New Zealand. D has given presentations at international conferences and published extensively. She edited and contributed to Craft is Political (Bloomsbury 2021).

References

| ↑1 | Laura Miller, Review: “The White Road,‘ by Edmund de Waal,” New York Times (Online), New York: New York Times Company. Dec 10, 2015. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Edmund de Waal, The White Road: Journey into an Obsession (Toronto, Knopf: 2015), 93. |

| ↑3 | Ralph Caplan, “Making More Than Sense,” The Haystack Reader: Collected Essays on Craft, 1991-2009 (Orono, ME: U of Maine Press, 2010), 331-344, p. 335. |

| ↑4 | Garth Clark, “How Envy Killed the Crafts,” in Glenn Adamson, ed., The Craft Reader (London: Berg, 2018), 445-453, p. 452- 453. |

| ↑5 | Editorial introduction, Journal of Modern Craft, 1(1) (March 2008): 5. |

| ↑6 | Journal Editors, “Modern Craft Studies: The Decade in Review,” Journal of Modern Craft, 10(1) (March 2017): 5- 18, p. 6 |

| ↑7 | Bruce Metcalf, Contemporary Craft: A Brief Overview,” in Jean Johnson, ED., Exploring Contemporary Craft: History, Theory and Critical Writing. (Toronto: Coach House Books & Harbourfront Centre, 2002), 13-23, p. 22. |

| ↑8 | Anthea Black and Nicole Burisch, eds. The New Politics of the Handmade: Craft, Art and Design, (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021) (p. 250, Figure 17.1). |

| ↑9 | Tony Fry, ‘Sacred Design I: A Re-creational Theory,’ in Discovering Design: Explorations in Design Studies, ed. Richard Buchanan and Victor Margolin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995): 190-218, 212. |

| ↑10 | Matthew Kiem, “Theorising a Transformative Agenda for Craft,” craft + design enquiry (2011): 33–48, 34-35. 18 Metcalf, “Craft Education.” |

Comments

Dear D Wood,

I am a maker, former editor, writer, etc., holding an MFA in ceramics, and an MA in English. I have formed a group of interested writers, professors, and others, that meets on Zoom on the third Thursday of each month to talk about writing. We have a guest presenter each month who presents for 20–30 minutes, and that is followed by lively discussion. I am wondering if you might be interested in being a guest presenter on May 19. I pay $100 USD for the short presentation and being a part of the discussion. We meet at 4pm US Eastern Time, but that can be adjusted to accommodate your schedule.

I look forward to hearing from you.

D this is so true…. Early writing and reading education and skill building throughout schooling in writing needs more support perhaps …… in order for many craftspeople to feel confident in their writing. What do you think?