Author in a research trip, having conversation with a weaving artisan in Ambon, Mollucas Island Indonesia 2015

Nancy Margried writes about a new technology for assisting artisans in expanding their traditional designs.

Woven cloth always has a dual standpoint in Indonesia. It is known as a sacred tradition resting on hundreds of years of indigenous skill, and as a craft product that relies on productivity. These two perspectives are intertwined: the traditionalist and the nonconventional. The first group tends to uphold the purity of woven cloth in its philosophical meaning, the social position of the wearer, its social use, design and production. Concurrently, the later group perceives the woven fabric and weaving from a more democratic and economic perspective, where altering the form and meaning of patterns is not prohibited: production and design are instead tied to market mechanisms, trend, and collaboration. This dynamic has caused tension for decades, but it also generates innovation.

Traditional skill and craft products are not foreign to the influence of technology. Weaving is included. Moreover, weaving is, in fact, a technique to produce cloth established by handloom technology. Consistent with how it creates, technology has always been the force of creation, production, and inspiration for the artisans over thousands of years. According to the History Cloth website, weaving is known to humanity since the Paleolithic era, and the first flax weaving found in Egypt is believed to date back to around 5000 BC. Fast forward to computing, automation, machine learning, and artificial intelligence era nowadays, traditional art and craft face two alternatives: to be empowered or exploited by technology.

According to Google Art and Culture, technology was adopted in textile weaving production from the start of the nineteenth-century in Germany and England. On the other hand, the advance technology and study seem to leave the traditional and small production stagnant, especially the indigenous artisanal weaving work. According to the writer’s experience working in traditional Indonesian textile for more than ten years, the tradition and philosophy of artisan weaving work restrict technological development. Additionally, the location of the traditional artisans in remote areas also hinders technology penetration. These barriers cause the loss of traditional patterns because there is no database system to keep them. Weaving skills and knowledge is lost. In response to this, some of the nonconventional groups previously mentioned have attempted to preserve this ancient tradition using technology: one of them is DiTenun.

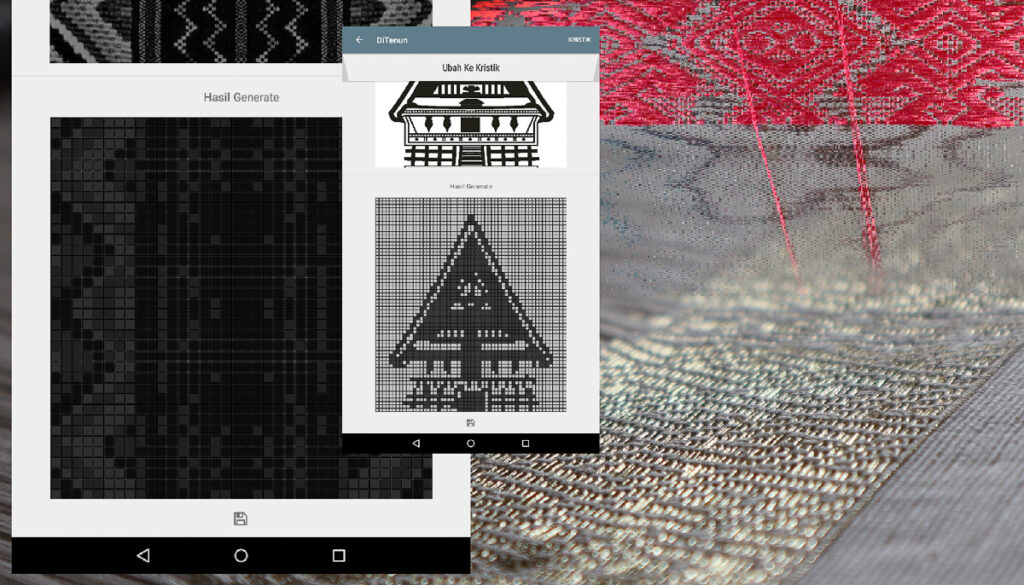

Illustration of DiTenun App with traditional weaving process Textile is the Tumtuman Ulos by Asti Panjaitan in Tobasa District North Sumatera Indonesia, photo illustration composed by Mirza Maulana

DiTenun is an artificial intelligence (AI) application to generate infinite numbers of weaving patterns based on the collection of weaving data. The data consists of traditional and authentic weaving patterns across Indonesia. DiTenun is the abbreviation of Digital Tenun Nusantara (Digital Archipelago Weaving). It started as collaborative research by Indonesian based tech and art startup called Batik Fractal Indonesia and Institute Technology Del, an Indonesian technology university in 2015. The idea is to create a digital application to help the traditional artisans across Indonesia creating new patterns based on their local and original patterns. The groundwork of this application is a growing traditional pattern database, which will contribute to building the accessible indigenous weaving patterns library. This ongoing research is funded by LPDP (Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education) under their RISPRO (Innovative and Productive Research Fund) platform.

The spirit of multidisciplinary collaboration is one of the main drivers for this ambitious project, especially when the intended users of the app are the traditional artisans. Even though “tech for good” or “tech for the non-tech savvy users” is one of the sexiest fields to work on for tech startups, to build an application for traditional art and craft such as weaving, is rarely done, especially in Indonesia. A large variety of different skills are needed to collaborate in this project, such as a large department of IT developers, math researchers, AI researchers and experts, UI/UX designer, traditional weaving and craft researchers, historian and experts, textile designers, experts in community development, small business and entrepreneurship, culture and tradition, and social media and branding. Due to the pandemic, all collaborations are mostly online this year. Slow progress is expected to take place, especially for a face-to-face app users trial and training, to improve both the software and the technology fluency of the artisan pilot group.

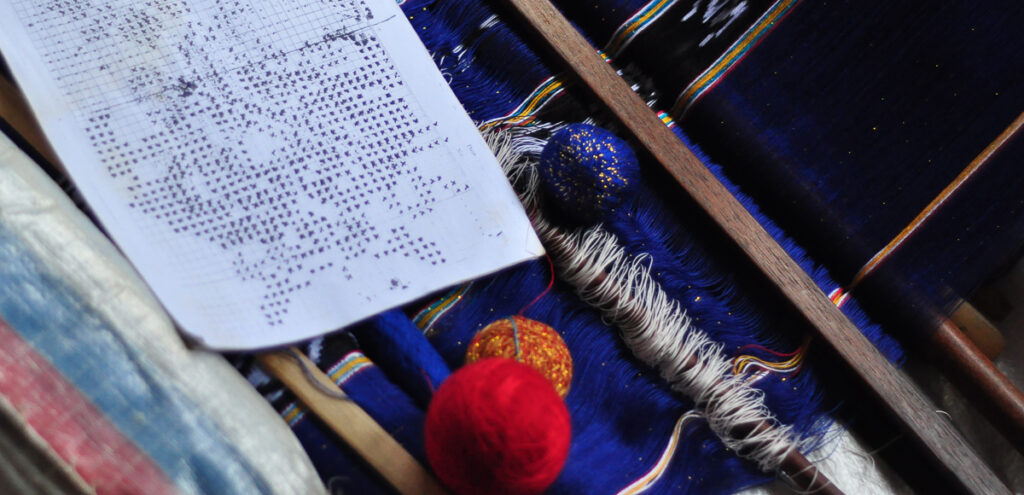

At the end of this development project in 2021, the working group expects to have a full function of DiTenun App Beta that contains a traditional weaving patterns database from different regions in Indonesia. The generator function will draw on source patterns and ornaments to create new designs with some level of user design intervention. The working group has registered the technology in Indonesia patent office in 2019. In the end, the non-tech-savvy users who live in villages will be able to have a printed coloured working sheet digitally or on paper, that they can use to produce new weaving patterns for buyers. The intended outcome is to embed technology in the world of traditional art, especially weaving, as well as to accustom the artisans with technology where they can utilise, explore, manage the technology to the best progress of the traditional art and to help their livelihood. All this take place in the under-developed technological structure of rural Indonesia.

Weaving pattern in a paper used as a working sheet. Handloom weaving process in artisan village Toba District, North Sumatera Indonesia

One of the biggest concerns for this project comes from the false belief that AI will take over the role of the human in creation. Without a doubt, AI will take over some of the tasks that are impossible to perform by a human being, such as processing a large amount of data in a short time. However, the role of AI in DiTenun is not to replace human creativity. AI here aims for skill automation and preservation of indigenous knowledge. To make sure that the artisans are in charge of technology is also to ensure the wisdom of cultural knowledge will continue living from generation to generation.

Yuval Harari mentioned in his book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century that artificial intelligence will be one of the most impactful advancements that society needs to consider. Unfortunately, the countries which still rely on human labour, manual skills, and handcrafted productions will become sidelined by the rise of AI. The implication is the massive exploitation of data and resources of these countries by the few Western data-savvy countries with the most advanced facilities and knowledge for their advantage. DiTenun is a heartfelt initiative from a small group of concerned people in Indonesia, for the traditional heritage preservation, and an unfeigned effort to champion and include the traditional artisans in the advancement of technology.

Sources

The Development of Textile Technology – TextilTechnikum — Google Arts & Culture

Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for 21st Century, 2018, Spiegel & Grau, Jonathan Cape

Author

Nancy Margried is a social entrepreneur with experience in traditional multidisciplinary research experience in traditional Indonesian textile, the application of technology on textile surface pattern designs, and artisans technology literacy empowerment. She co-founded two startups; Batik Fractal Indonesia and Digital Tenun Nusantara aim as the vehicles to extend technology in solving some of the prominent problems in the traditional textile field. Nancy is a Chevening scholar, a TEDx speaker, and she lives in Indonesia.

Nancy Margried is a social entrepreneur with experience in traditional multidisciplinary research experience in traditional Indonesian textile, the application of technology on textile surface pattern designs, and artisans technology literacy empowerment. She co-founded two startups; Batik Fractal Indonesia and Digital Tenun Nusantara aim as the vehicles to extend technology in solving some of the prominent problems in the traditional textile field. Nancy is a Chevening scholar, a TEDx speaker, and she lives in Indonesia.