(A message to the reader.)

This article imparts the virtues of a living Japanese craft and introduces readers to the profound wisdom that comes from the quotidian practice of drinking tea.

It is co-authored by two Japanese women, Yoko Akama and Yoko Ozawa. Their close friendship over many years has been knitted through a passion for pottery and sharing resonant life-experiences of working in Melbourne, Australia. Akama is a design researcher and educator at RMIT University, Melbourne, who has written extensively about Japanese philosophy. Ozawa is a celebrated artist who teaches ceramics in Melbourne and exhibits her work in Japan and Australia. The catalyst for this article was Ozawa’s visit to Hagi, Japan, in June 2018, and the subsequent conversations with Akama that led to a rich discussion around philosophies adjacent to Akama’s research and writing.

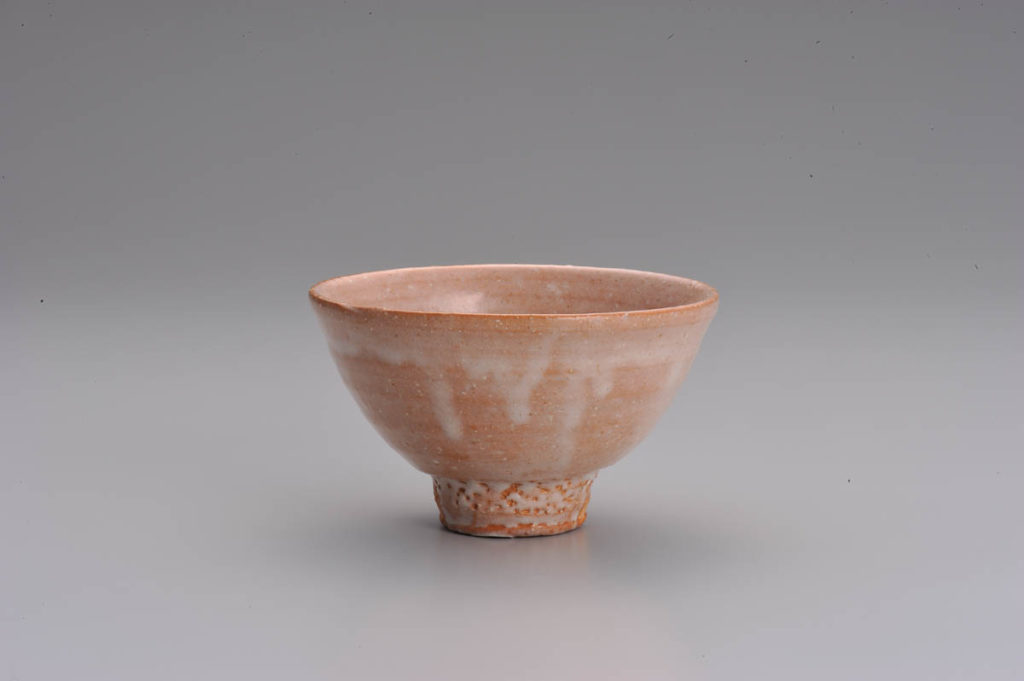

Hagi ceramics is renowned for using unrefined clay that gives a short yet smooth texture.1.Hagi clay has a complex constitution. See more details here (in Japanese) This is fired at low temperatures to create a soft, porous constitution that imbibes the tannin from the tea, thereby altering its colour through repeated use. Its deliberate, fragile nature also makes the teacup leaky and easy to break. While this may sound impractical, the changes in a cup’s expression through drinking tea are cherished by many who encounter an intimacy with impermanence, incompleteness and inter-relatedness.

Such characteristics are often associated with wabi sabi, but this must not be confused with the ways it has been culturally appropriated as an aesthetic for a rustic, natural, simple, aged style. This misrepresents the depth of philosophy and worldview that lies underneath. This depth can be sensed in the story from the 8th Okadagama Hagi-ware master, Yu Okada, who is also recognised as the Yamaguchi Prefecture Intangible Cultural Assets holder. He explains how in cha-no-yu (Way of Tea), drinking maccha green tea is like imbibing the viridescence of nature as a continual becoming through intimacy. In other words, the act of drinking tea from a porous and ever-changing vessel is an embodied practice of impermanence, incompleteness and inter-relatedness. Okada laments that anyone can order the local clay over the internet and make Hagi pottery. However, living in Hagi, sourcing the clay nearby and firing the family kiln for eight generations demonstrates a living practice that is woven through land, place, time, climate and people. The Hagi teacup created by Okada, in this view, is inseparable from this interrelatedness. Through its impermanence and incompleteness, it invites further layers of interrelatedness with others by imbibing tannin from another fresh brew to evoke a continual becoming.

Incompleteness is very much alive in Ozawa’s work through the notion of the fog. She studied Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) during her graduate studies and was inspired by works such as the famous Shōrin-zu byōbu (Pine Trees screen) by Hasegawa Tōhaku, an ink painting of a pine forest shrouded by mountain mist 2.This Japanese ink painting by Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610) is considered to be one of the pinnacles of art created during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (sixteenth century), is listed as a National Treasure and can be seen at the Tokyo National Museum.

The very absence of marks invites the viewer to “enter” and participate in becoming-with through their own perception and imagination. Such exemplary work imbues emptiness as Ma (間). Ma gives form to formlessness (or emptiness), thus accentuates an awareness of totality and a heightened relational sensitivity 3.Akama has written several scholarly papers on Ma. See Akama, Y. (2015). Being awake to Ma: designing in between-ness as a way of becoming with. Co:Design: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 11(3–4): 262–274 and Akama, Y. (2019). A finger pointing to the moon: Absence, emptiness and Ma in design. In G. Coombs, A. McNamara, & G. Sade (Eds.), Undesign: Critical Practices at the Intersection of Art and Design (pp. 111–121). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Many philosophies of emptiness evolved through the works of such artists, poets, monks, scholars and teachers to maintain a living practice of taking non-being, formlessness or emptiness as the ground for being. The sage, Lao Tzu is believed to have expressed: “Clay is kneaded into a vessel; the usefulness of the vessel lies in the space where there is nothing.” Echoing this famous poem, a celebrated Japanese designer, Kenya Hara describes the potentiality of Ma through an empty bowl: “A creative mind… perceives it as existing in a transitional state, waiting for the content that will eventually fill it; and this creative perspective instils power in the emptiness.”4.The Lao Tzu quote comes from a longer passage, translated by Kimura, Y. G. 2004. The Book of Balance: Lao Tzu’s Tao Teh Ching. “Thirty spokes share a hub; The usefulness of the cart lies in the space where there is nothing. Clay is kneaded into a vessel; The usefulness of the vessel lies in the space where there is nothing. A room is created by cutting out doors and windows; The usefulness of the room lies in the space where there is nothing”. While the material contains utility, the immaterial contains essence.

Similarly, Ozawa draws inspiration from Japanese landscapes surrounded by fog and her work permits an imaginative engagement through its delicate incompleteness. The exhibition in September 2018 called Tsutsumareru – Surrounded explored notions of memory and obscurity as a way to glimpse at distant scenes from her past. Ozawa explains, “‘Tsutsumareru’ attempts to convey the atmosphere between objects and their surroundings. In my memories of experiencing this, it’s the enveloping fog, the sensation of the wind, the temperature and the stillness of the air that afforded me an awareness of it.” 5.Akama and Ozawa both attended a public talk by Kenya Hara (Art Director of Muji, Design Professor at Musashino Art University, Japan and one of the most renowned Japanese designer) on ‘Emptiness’ at RMIT University. His quote is from Hara, K. (2011). White. Zurich, Switzerland: Lars Müller, p. 28.

Ma can heighten sensitivity to the relational in-betweens, like atmospheres and a landscape enveloped in fog, to invite unlimited imagination, just like an empty cup waiting to be filled with a fresh brew of tea.

Author

Yoko Akama is Associate Professor in the School of Design, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Her practice is shaped by various Japanese philosophies of between-ness and mindfulness, to consider how pluriversal futures can be designed together. She is a recipient of several national and international awards for collaborative work with self-determining Indigenous and regional communities. Current works include a co-authored book on Uncertainty and Possibility (2018) by Bloomsbury, and co-leading the Design and Social Innovation in Asia-Pacific network.

Yoko Akama is Associate Professor in the School of Design, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Her practice is shaped by various Japanese philosophies of between-ness and mindfulness, to consider how pluriversal futures can be designed together. She is a recipient of several national and international awards for collaborative work with self-determining Indigenous and regional communities. Current works include a co-authored book on Uncertainty and Possibility (2018) by Bloomsbury, and co-leading the Design and Social Innovation in Asia-Pacific network.

The journey to Hagi

Since being in Australia, I have mostly seen the contemporary Japanese ceramists. I was amazed by the individuality of these young generations’ work and practice. But a question was always remaining. How is the traditional pottery at present? I have also noticed that now I live away from Japan, I want to know about Japanese traditional culture more, especially to pursue and reveal the true nature of ceramics.

I was lucky enough to stay with my friend’s family in Hagi, in a well-known historical pottery city in Yamaguchi Prefecture for one month. I have gratitude for this opportunity to meet Yu Okada. The discussions on practice with this traditional master deepened my relationship with ceramics. I would like to share my experience of the culture

- Yu Okada, throwing on his wooden kicking wheel, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Yu Okada, throwing on his wooden kicking wheel, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Okada’s wooden kicking wheel and his studio, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Okada’s Noborigama (woodfiring kiln) has been inherited through eight generations, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Yu Okada, Ido Tea-bowl, 2018; photo courtesy Yu Okada

- A entrance of a tea room, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Miwa Seigado teabowl gallery, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Sake offered to the god of the kiln to pray for the safe and successful firing, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- The smell of Natsumikan everywhere in the town in June, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- The branching bay in Hamasaki town, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Drying fish by the sun and the breeze from the sea, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Hamasaki town, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- The warriors graveyard in Toji temple

- Natural clay to make Hagi ware, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Sunset and Hagi’s symbol of Mt Ishitsuki, 2018; photo: Yoko Ozawa

- Okada, Ash covered tea bowl 裕―灰被茶盌

Special thanks to Okadagama – Okada Yu and his son Takashi, Hamasaki shicchorukai community, Mina tea bowl gallery, and Minoru and Kyoko Kogaya.

Artist

Born in Japan, Yoko Ozawa is a Melbourne-based artist who studied Japanese painting and graphic design in Tokyo. Ozawa began practising in ceramics in 2003 and has been in Melbourne a base of her creation since 2010. Since then, she has been part of numerous exhibitions and events in both Australia and Japan. Ozawa wonders about natural phenomena such as fog, rain, snow, light and shadow, and things that we cannot see, like a breath of air or scent. While working with subtle tones and simplistic forms, she explores the stillness and space between objects, something defined by Yohaku (blank space), a Japanese painting concept which she studied early in her career.

Born in Japan, Yoko Ozawa is a Melbourne-based artist who studied Japanese painting and graphic design in Tokyo. Ozawa began practising in ceramics in 2003 and has been in Melbourne a base of her creation since 2010. Since then, she has been part of numerous exhibitions and events in both Australia and Japan. Ozawa wonders about natural phenomena such as fog, rain, snow, light and shadow, and things that we cannot see, like a breath of air or scent. While working with subtle tones and simplistic forms, she explores the stillness and space between objects, something defined by Yohaku (blank space), a Japanese painting concept which she studied early in her career.

Related stories

Imagining a nostalgic future: The cosmic ceramics of Douglas Black

The gate is open: Guan Wei and Jayne Dyer in China

Eunbum Lee – 법고창신, the spirit of creating the new, based on the old

Forest of Craft ✿ A map of nature's treasures

Naga Mae Daw Serpent: Maternal energy uncoils in Myanmar

The nine-yard sari: Bolts of love in clay

References

| ↑1 | Hagi clay has a complex constitution. See more details here (in Japanese) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This Japanese ink painting by Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610) is considered to be one of the pinnacles of art created during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (sixteenth century), is listed as a National Treasure and can be seen at the Tokyo National Museum |

| ↑3 | Akama has written several scholarly papers on Ma. See Akama, Y. (2015). Being awake to Ma: designing in between-ness as a way of becoming with. Co:Design: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 11(3–4): 262–274 and Akama, Y. (2019). A finger pointing to the moon: Absence, emptiness and Ma in design. In G. Coombs, A. McNamara, & G. Sade (Eds.), Undesign: Critical Practices at the Intersection of Art and Design (pp. 111–121). Abingdon and New York: Routledge. |

| ↑4 | The Lao Tzu quote comes from a longer passage, translated by Kimura, Y. G. 2004. The Book of Balance: Lao Tzu’s Tao Teh Ching. “Thirty spokes share a hub; The usefulness of the cart lies in the space where there is nothing. Clay is kneaded into a vessel; The usefulness of the vessel lies in the space where there is nothing. A room is created by cutting out doors and windows; The usefulness of the room lies in the space where there is nothing”. While the material contains utility, the immaterial contains essence. |

| ↑5 | Akama and Ozawa both attended a public talk by Kenya Hara (Art Director of Muji, Design Professor at Musashino Art University, Japan and one of the most renowned Japanese designer) on ‘Emptiness’ at RMIT University. His quote is from Hara, K. (2011). White. Zurich, Switzerland: Lars Müller, p. 28. |