Eina Ahluwalia reflects on the impact of her Wedding Vows collection that presented a powerful response to violence against women.

The demure figure of Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s celebrates a model of gentle femininity that appears to seek adornment with sparkling jewels. Indian culture introduces an alternative model of female love which is capable of great violence. In the culture of southern India, the revered story Silappatikaram tells of the epic heroine turned goddess Kannagi, who is enraged by the wrongful murder of her husband for an anklet, which leads to the destruction of the entire city of Madurai. Today, Kannagi is still worshipped in temples such as Kodungallur Bhagavathy in Kerala, where devotees channel her rage in an annual festival.

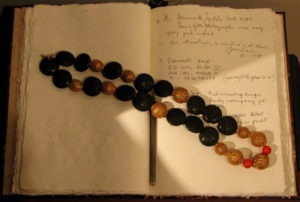

A contemporary echo of this can be found in the work of Eina Ahluwalia, a Kolkata-based jewellery artist. The Wedding Vows jewellery range that she performed at Mumbai Fashion week is still legendary for the way it confronted the issue of violence against women in India. Ahluwalia uses jewellery to critique a patriarchy that positions women in a passive role. An object like the mangalsutra, for instance, is normally only bestowed on the bride by the groom. Ahluwalia has produced a mangal sutra for the bride to give the groom as a reciprocal act.

We speak with Eina Ahluwalia to reflect on this work and its subsequent impact.

✿ What inspired you to make a mangalsutra for the groom?

Every Indian culture and sub-culture whether divided by religion or state of residence has a signifier for married women. Symbols that the woman must wear to publicly show that she has been handed over from father to husband, and now is the sole property of the husband.

In the North there is the mangalsutra, black bead necklace, in the South the tali, in Maharashtra the green glass bangles, in Bengal the red coral and white shell bangles, as well as the Loha, Parsis have the red glass bangle, the list goes on. A lot of Indian women wear the Sindoor, red vermillion in the parting of their hair, others wear toe rings, and wearing bangles is mandatory for married women as empty wrists signify widowhood.

In fact in the old days, when the husband died one of the rituals was for the wife to break her glass bangles against something hard while they were on her wrist, as a rite of passage into widowhood- a state where no ornamentation was allowed because she belonged to no man, and so there was no need for physical beauty nor anything to enhance it. She was to wear a white sari, shave off her hair and sent off (or abandoned) to live in a shelter for widows (especially in holy cities like Varanasi or Vrindavan) to spend the rest of her life in denial of all worldly pleasures, removed from the rest of the society as she was considered inauspicious or at the very least, an unnecessary burden. This was especially tragic in the case that very young girls who were married off to very old men, resulting in a large number of young women in these shelter homes, living their life in non-existence.

Thankfully things have changed and in contemporary India this expulsion of widows is rare, and in urban, educated India a lot of women who have lost their husbands continue to live meaningful lives as active participants of their families and society.

However, the obsession with marriage remains prevalent, and with patriarchy so deeply entrenched, many women themselves covet and flaunt these markers of being married.

In contrast, of course, there is no symbol that a man wears to reveal his marital status, as he is never owned by anyone, he is truly free.

To bring the idea of equality in marriage and parity in belonging, I proposed the concept of a mangalsutra for men, something that the bride will make the man wear at the time of marriage (the reverse is the customary norm). I explored the idea through a contemporary dance performance where the woman puts a large mangalsutra made of black volcanic rock and carved metal beads around the man’s neck and sindoor on his head, continuing into a dance of tenderness and love. This was 10 years ago in 2009, and many in the intimate audience that stood surrounding the performers in the gallery space were taken aback by the subversion of the rituals. The idea that equality should be such a radical notion in itself reveals how far we still have to go.

✿ What kind of response did you get for your Wedding Vows collection?

That Wedding Vows has remained our most popular collection till date is a tale about how rampant violence is in the experience of womanhood. The collection spoke about physical, sexual, emotional, mental, financial, verbal violence in marriages, and resonated with the gender experiences of women across the world.

During the launch runway show at Fashion Week, when the Kirpan necklace was opened at the head ramp there was a collective gasp from the audience; goosebumps and tears were reported throughout the show. Over the years we have received emails telling us how some of these pieces have become the symbol of the journey out of violent marriages, and others saying how they serve as a reminder of their personal strength. We have had brides buying these for their weddings, mothers for their daughters, and my favourite of all, wonderful husbands buying it as a symbol of love and respect for their wives, even though this jewellery is not gold.

None of our other collections has had the impact, emotional connect and the transformational effect that these pieces have had, and this is still one of our most remembered collections.

✿ Have you seen any developments in Indian weddings that reflect a greater equality between men and women?

Yes, marriage as an institution is undergoing a slow but steady change even in India. With women being educated, getting jobs, and earning money, husbands are also beginning to contribute to the domains that were traditionally considered the responsibility of the wife. I see this more in the younger couples of today. This has not come easy. There are a few generations where the struggle for equality has ended in divorce, which has lead to where we are today.

There are some young people who are questioning the very idea of marriage and the relevance and need for it in today’s context..

✿ Are there any particular Hindu Gods that inspire your work?

I am not inspired by any one God, but more by the idea of everyone having their own Gods, and the fact that we should co-exist with mutual respect or each other’s God’s and ideologies. This is especially relevant in today’s context when bigotry and fascism are resurfacing and threatening the ideology and moral fibre of our country.

✿ Do you see the potential for same-sex weddings in India and would it use a different kind of jewellery?

In the current political scenario, I don’t foresee the legalisation of same-sex marriages in India. However, even though the pace of change is really slow, I hope for a more liberal governance in the future, and with all the activists lobbying for it, it will become a reality. I think that as marriage becomes more equal, whether same sex or heterosexual, the jewellery that revolves around it will be that of celebrating moments or milestones rather than that of proprietorship.

✿ What themes are you working on now?

Freedom, resistance, dissent, equality, co-existence, mutual respect and love

Artist

Eina Ahluwalia is a Kolkata based jewellery artist who used her work for social commentary and activism. Her work is soulful, spiritual and strong, and meant to be worn as personal totems, everyday reminders or a way to assert a point of view. It is also her crusade to subvert the paradigm of jewellery as a means of ornamentation loaded with patriarchal symbolisers, a way to appear more beautiful to the other; and reclaim and redefine it as a woman’s way of expressing her independent identity, as a symbol of empowerment, purely for her own enjoyment, as a celebration of herself.

Eina Ahluwalia is a Kolkata based jewellery artist who used her work for social commentary and activism. Her work is soulful, spiritual and strong, and meant to be worn as personal totems, everyday reminders or a way to assert a point of view. It is also her crusade to subvert the paradigm of jewellery as a means of ornamentation loaded with patriarchal symbolisers, a way to appear more beautiful to the other; and reclaim and redefine it as a woman’s way of expressing her independent identity, as a symbol of empowerment, purely for her own enjoyment, as a celebration of herself.