Luise Guest writes about an exhibition at 16albermarle Project Space and Delmar Gallery of Thai artists who skillfully and delicately bind together disparate elements of their world.

Kusofiyah Nibuesa

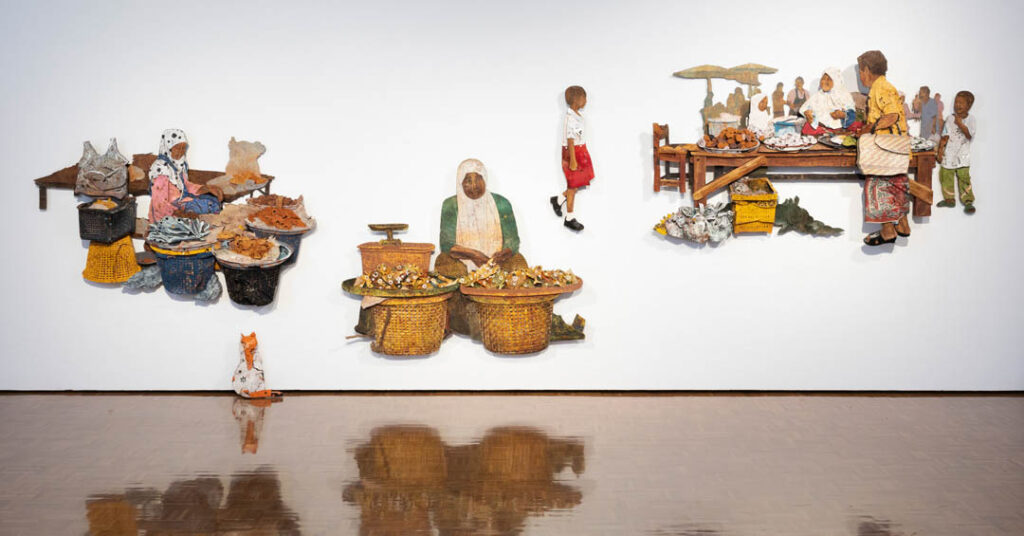

Kusofiyah Nibuesa, Deep South Market 2 2022, assembled cut paper, 160 x 156 x 18 cm; Deep South Market 2016, assembled cut paper, 135 x 110 x 10 cm; Multicultural 2021, assembled cut paper, 120 x 240 x 19 cm

Kusofiyah Nibuesa invites us into a world far from the visual clichés of tourist Thailand. Her intricately detailed paper relief sculptures transport us to Thailand’s far south, a region close to the border with Malaysia that has suffered ongoing religious and ethnic tension and unrest. But rather than focusing on this instability, Nibuesa represents instead a harmonious multicultural community. Working with cut paper, printing and stencilling techniques to create immersive images of daily life, she depicts a world in which all Thai citizens—Muslims, Buddhists and Chinese—co-exist peacefully.

A member of the Muslimah Collective, a collaborative group of five female Muslim artists, Nibuesa explores her cultural and faith heritage through works depicting the life of the bustling markets of Pattani. Textile designs become markers of identity: a man wearing a sarong and a loose, patterned shirt pushes a cart laden with bags of rice or market produce, and veiled women seated behind wicker baskets overflowing with fish, fruit, and spices wear intricately patterned robes.

Nibuesa, who studied printmaking at Silpakorn University, makes astute and carefully considered decisions that enhance the visual and emotional impact of her works. Multicultural, The Cart (both 2021), Deep South Market (2016) and Deep South Market 2 (2022) each suggest an ambiguous narrative—tiny vignettes of daily life that might otherwise go unnoticed are enlarged, becoming newly significant. Removing her subjects from their busy backgrounds, overlapping her paper forms so they cast shadows against the gallery wall, the artist enables us to focus on individual men and women. Navigating tensions between artistic tradition and contemporaneity with works that experiment with techniques of sculptural printmaking and papercutting, Nibuesa celebrates the lives of those who are often invisible in the geopolitical discourses of our time. In her work, ordinary people and the routines and rhythms of daily life are not so ordinary after all.

(Mariem) Thidarat Chantachua

“One thread alone is fragile”, says Thidarat Chantachua, “but many threads together are stronger.” She is referring, literally, to her technique of “drawing” complex architectural geometries with needle and thread, but she is also speaking metaphorically. Thidarat Chantachua studied painting, sculpture and graphic arts at Silpakorn University, but now, eschewing more conventional art materials, she adapts embroidery techniques she learned as a child from her mother to create immersive textile works. Escher-like perspectival illusions of space and depth, and clever contrasts of lighter and darker web-like threads, draw the viewer into alluringly beautiful, ambiguous spaces.

At the heart of Chantachua’s practice is her Islamic faith and its spiritual and artistic traditions. She conveys this theme in a highly contemporary way, integrating the decorative motifs of Islamic art with an abstract language influenced by western modernism – which itself was often informed by non-western religious and spiritual traditions. Chantachua’s knowledge of traditions of Thai and Islamic painting and architecture is evident in the intricate geometry and repeated patterning in each work. Her starting point is often with the rectangles and triangles found in the sacred geometry that is the foundation of Islamic art and architecture. Using Photoshop, she creates dizzying geometric tessellations overlaid onto the forms of interior and exterior spaces, before transferring the designs onto fabric.

Thidarat Chantachua believes that we must find it in our hearts to act together for the common good. As a Muslim living in Bangkok, in a predominantly Buddhist culture, she is acutely aware of the need for people to overcome cultural and religious differences and find connection. For Chantachua, her thread becomes a symbolic means of emphasising the bonds that unify people.

Imhathai Suwatthanasil

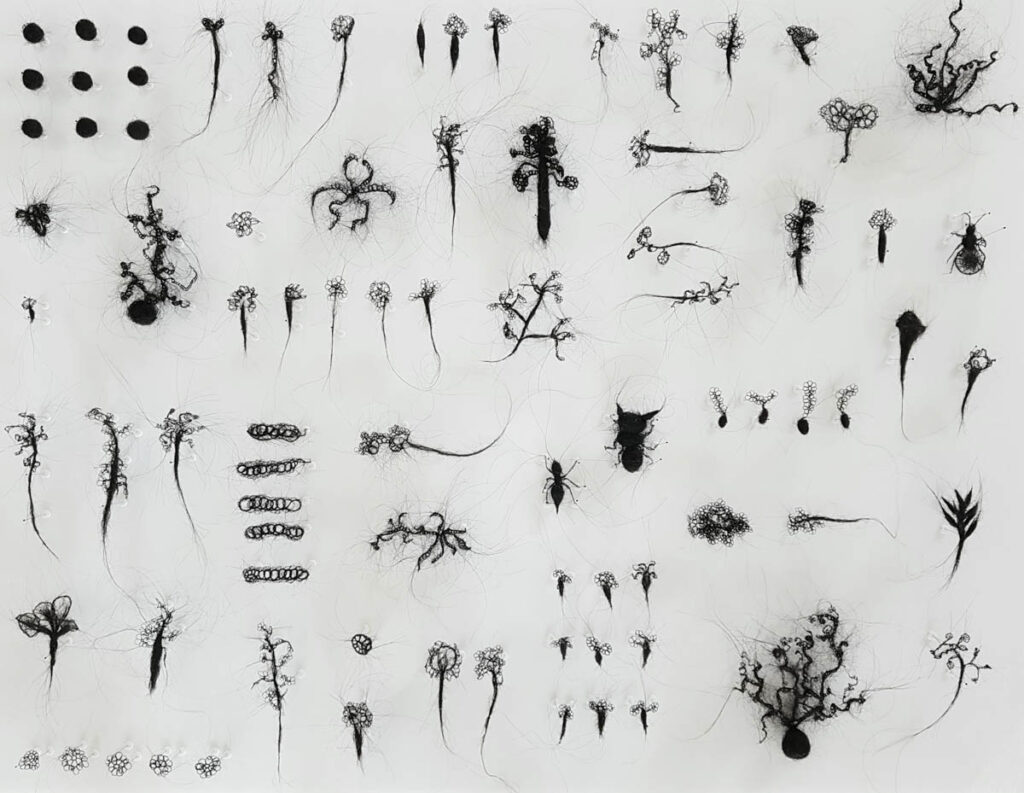

- Imhathai Suwatthanasilp, Ash Flowers 2022 (detail), human hair, sewing thread, glue, 70 x 270 x 12; Jenni Carter Photography

- Imhathai Suwatthanasilp, Dark Hope 2021, human hair, sewing thread, 61.5 x 93 cm

Imhathai Suwatthanasilp’s primary medium is a material not usually associated with contemporary art: she weaves, crochets, knots, stitches and embroiders human hair into sculptural forms that examine aspects of her personal world, as well as reflecting on broader social issues. For Ash Flowers (2022), Suwatthanasilp explored the degraded farmland and rice fields around her home in northern Thailand. She had become acutely aware of the ecological devastation caused by farming practices—poor farmers burn their rice fields as a form of land clearing and use increasing amounts of dangerous herbicides to produce commercially viable crops. Suwatthanasilp asks us to consider the environmental and human cost of these practices. Using donated hair, she patiently created tiny, fragile replicas of twigs, seeds, weeds, and insects retrieved from the blackened fields. Displayed in a vitrine in the gallery space they resemble museological specimens—or, perhaps, artifacts of a lost civilisation.

Hair provokes strong reactions. Often considered sensual or erotic, it can also elicit feelings of discomfort, and even disgust. Dark Hope (2022) is a slightly repellent, yet completely recognisable replica of the Thai flag made of hair woven into striped fabric, with hairy threads protruding from all sides. Suwatthanasilp is making a courageous political statement. The work alludes to Section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code, which provides prison sentences of up to 15 years for anyone who “defames, insults or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent”. Since 2020, in the face of widespread protests demanding greater human rights and freedom of expression, the Thai government has increasingly used this law to investigate protesters. A flag, symbol of patriotism and pride, here becomes disturbingly animalistic. Suwatthanasilp calls into question the “purity” of nationhood promoted by government propaganda—in Thailand, and globally.

Surajate Tongchua

- Surajate Tongchua, PRICELESS (Plant) 2020, papier-mâché, 44 x 74.5 x 60 cm

- Surajate Tongchua, PRICELESS (Day:Day) No. 2 2022, receipt paper and acrylic on canvas; Jenni Carter Photography

Surajate Tongchua studied printmaking at Chiangmai University, graduating in 2010. His work has been exhibited widely in solo and group exhibitions in Thailand and also in Singapore. His four works in Other Possible Worlds are part of a larger project that began in 2014 with Thailand’s latest coup d’état. They represent an expanded field of printmaking that includes the use of found materials. Priceless refers on one level to the simple economics of the cost of living, but as the artist says, it also refers to the “lives, opportunities, rights and freedoms” that have been impacted by the rule of the military junta.

Tongchua was lined up at the bank on the day of the coup, and he began to think about how his VAT payments were used to support the government. He started to collect receipts showing his own and his family’s daily expenses, and then put the collection amassed over several years through a paper shredder, using the strips to create abstract “paintings”. Deconstructed and destroyed, the receipts are meaningless, calling into question the value of the items originally purchased, and a taxation system calculated to give more to the rich than to the poor. Audiences might view these works through a purely aesthetic prism, as abstract compositions, or they might think about the invisible mechanisms at work that assign value to some things—and some people—and not to others.

In addition to the 2D works, Tongchua created 3D pots, vessels and vases made of papier-mâché using Chinese language newspapers, primary school social science textbooks and receipts. The artist explains his choices: “Chinese newspapers refer to Chinese-Thai investors who have connections with the government. The social science textbooks have never changed content and aim to promote the cult of personality.” Tongchua’s greyish papier-mâché tree growing out of its papier-mâché pot seems like the opposite of growth and abundance.

Other Possible Worlds: Contemporary Art from Thailand was at Delmar Gallery and 16albermarle Project Space 25 June to 30 July 2022.

About Luise Guest

Dr Luise Guest is an independent researcher, writer and curator based in Sydney. Her writing has been published in The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, The Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art, Australasian Art Monthly, Artist Profile, Yishu Journal, Ran Dian and CoBo Social. Her focus for many years has been on contemporary art in/from China, however her research interests include the contemporary art of the Asia Pacific region more broadly.

Dr Luise Guest is an independent researcher, writer and curator based in Sydney. Her writing has been published in The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, The Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art, Australasian Art Monthly, Artist Profile, Yishu Journal, Ran Dian and CoBo Social. Her focus for many years has been on contemporary art in/from China, however her research interests include the contemporary art of the Asia Pacific region more broadly.