The Timor-Leste Vaihoho tradition of song offers a connection to the past that current generations are keeping alive through digital recordings.

Message to readers from Ildefonso da Silva, Daniel Valentim Pereira and Nelinha Pereira

✿

Love and war, threshing rice, hauling a tree from the forest, planting the post of a house, harvesting sea worms, passing the time.

These are the life journeys that make up the Vaihoho song-poems of Lautem in far east Timor-Leste. In danger of vanishing with the last of the knowledge-holders, cultural researchers have been collecting these songs in written and visual form in the belief they can be carried forward.

When Fataluku cultural leader and researcher Justino Valentim began making the journey to remote Timor-Leste villages to record Vaihoho song-poems, his intention was to keep the oral tradition alive for future generations so they would know their own culture.

“This project brings renewed spirit to revive a culture that our young people do not yet know or value.”

But Justino’s untimely death in 2014 abruptly halted his project. The large collection of Vaihoho he had so carefully documented remained hand-written on paper, locked in a cupboard in his family home in Lospalos.

Now, years later, they are finally being digitised by Lospalos cultural researcher Idlefonso da Silva, with support from Justino’s son Daniel Valentim and culture-based development organisation Many Hands International.

In the process, Ildefonso and Daniel are engaging with their cultural past. They are revisiting the villages, tracing Justino’s steps to check poems are accurate and attributed to the right village or singer. They have become the carriers of a conversation that considers the place of Vaihoho in today’s Lospalos.

A life’s journey in song

For an older generation, critically endangered Vaihoho song-poems remain the most valued oral form through which Fataluku history and cultural stories are shared.

Poetic, they tell of love and war among other stories of village life — threshing rice, hauling a tree from the forest, planting the post of a house, harvesting sea worms, walking, passing the time.

As Lospalos-based cultural researcher Idlefonso da Silva explains:

“Vaihoho is a tool to convey important messages about life and culture. It was, once, one of the few ways stories and lessons were conveyed.

“The song-poems gave insights into ancestral lines or what we call our ratus (tribes), and past allegiances during times of difficulty. They sometimes used veiled speech, and told of many other stories that help us understand our past and inform our future.

“They taught us how to know each other, how to respect each other and how to know our own cultural identity, because culture can strengthen our bond as a people and a community.”

Drawing on metaphor and symbolism, Vaihoho uses both daily Fataluku language and rare or archaic words that are themselves in danger of loss.

Often, the song-poems are about love. Singers have relayed how songs were sung to ask a lover to wait so they can prepare to be married and ‘journey through life together’, as well as how they used songs to arrange secret meetings and express feelings for each other.

The many years of Timor-Leste’s conflict also made their way into song-poems. War song, halu vaihoho, tells of the tragedy and massacres when Indonesia invaded. Many people were killed, and some were able to escape by hiding in forest areas. The song uses the metaphor of a tree that fell across the land, killing a large number of people to describe these lives lost.

Veiled speech is used in other songs too, such as suku rasa vaihoho — a poem about the need for humility when one accumulates wealth.

- Women from the community of Tutuala singing Vaihoho, 2015; photo: Ildefonso da Silva

- The community of Tutuala singing Vaihoho, 2015; photo: Ildefonso da Silva

- The community of Tutuala singing Vaihoho, 2015. Photo_ Ildefonso da Silva.

Carrying forward the past

When Ildefonso da Silva and Daniel Valentim received the funding support they needed to continue the work of Justino Valentim, they essentially became the new carriers of this Vaihoho knowledge.

On their journey back to the villages where Justino had started collecting Vaihoho, 22 years earlier (from 1999–2014), they found more knowledge-holders had passed, and there were forgotten parts of the stories, highlighting how critical it was to record and digitise what they could.

Idlefonso explains:

“Twenty-three Vaihoho practitioners contributed to the original collection of Justino’s … we were able to identify only 16 of these Elders. Of those, seven had passed away and one was in hospital. The remaining eight were located throughout Lautem, and it was those eight Elders we visited.

“We transcribed each item in the collection to share with them so they could verify the accuracy of each poem, and help us prepare interpretative text.

“They remembered Justino’s project and explained they performed the poems for him several times, while Justino transcribed the poems … but when we asked them to recite the poems, five of the eight practitioners could not remember the poems in full.”

- Ildefonso da Silva (left) and Regina da Cunha (right) review the transcript of the Vaihoho Regina performed for Justino between 1999–2014, in Suku Muapitine, Aldeia Malahara, 2021. Photo: Daniel Valentim Pereira.

- Ildefonso da Silva (right) shares a past recording with Marcelino da ConceiÇÅo (left) who sings Vaihoho in the video, in Suku Bauro, Aldeia Nanafoe, 2021; photo: Daniel Valentim Pereira.

Digitised on a resource library is perhaps an odd place for Vaihoho song-poems to live, but embedding them in technology might be the only way these songs find their place in a changed world, somehow making their way to a new generation knowledge-holders and knowledge-makers, giving these stories over to be rekindled or used in new ways.

Says Ildefonso:

“Nowadays, young people spend their time learning from technology, leaving behind what they inherited from their ancestors, forgetting their own culture because they live in a time of globalisation.

“This project brings renewed spirit to revive a culture that our young people do not yet know or value. Through this project, information about culture can be disseminated through social media and websites so people can access them, and continue to develop them.

“Some songs are still relevant with today’s era and some are not. But I think song-poems still carry a lot of meaning for young people. I feel we can revive them and develop them again.”

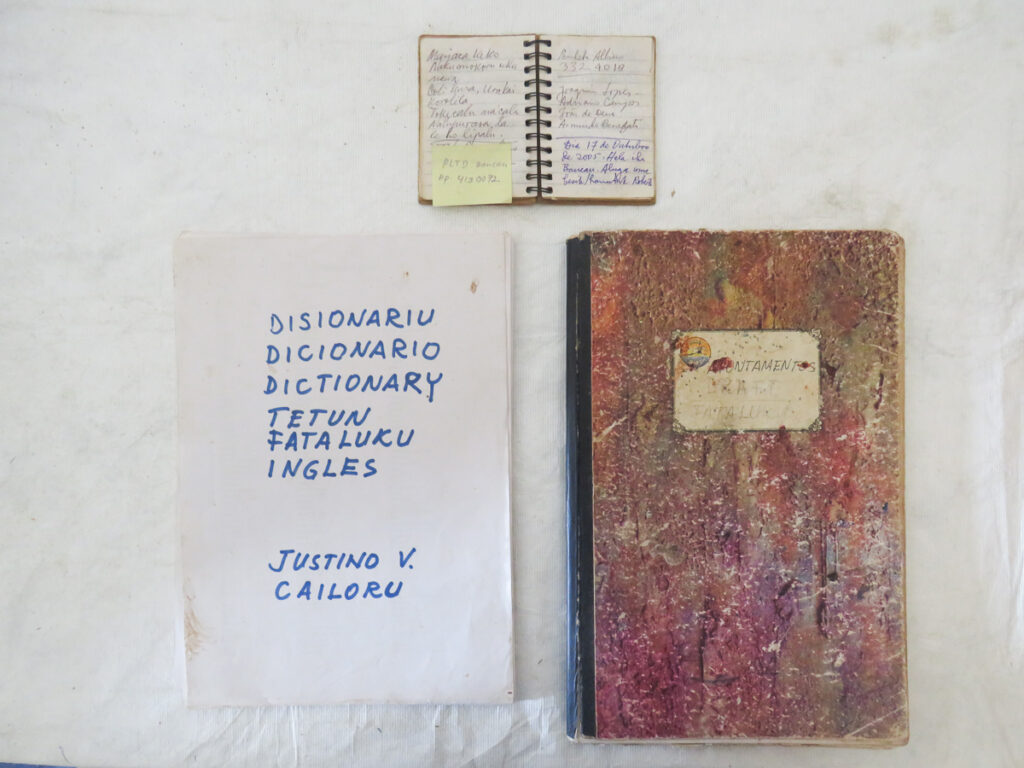

Among Justino’s collection was a draft Fataluku dictionary. As the Fataluku language has not been a written language until very recently, this is a valuable resource to accompany Vaihoho. Hand-written Vaihoho song-poems and Fataluku dictionary; photo: Ildefonso da Silva

“There are very interesting stories that I have learned through this project, and I feel proud when I read these song-poems because it was new for me, even though it is my own culture.

“I also feel proud to now work with Daniel Valentim on this project, as together we learn and continue what Justino started.

“Culture is our identity. It can strengthen human relationships and community. Culture can support love, peace and stability with many problems able to be resolved through solutions that stem from culture.

“As a researcher, I want to invite all of us to continue to uphold our own culture and promote it so that it does not disappear in the future.”

About Ildefonso da Silva, Daniel Valentim Pereira and Nelinha Pereira

Idlefonso da Silva has been a Cultural Researcher with Many Hands International for more than nine years, where he is helping to safeguard and publicly disseminate a significant collection of cultural elements from across the region. He is the Senior Researcher and coordinator for this project. Ildefonso has a background in political science and is passionate about learning ancient high Fataluku language.

Idlefonso da Silva has been a Cultural Researcher with Many Hands International for more than nine years, where he is helping to safeguard and publicly disseminate a significant collection of cultural elements from across the region. He is the Senior Researcher and coordinator for this project. Ildefonso has a background in political science and is passionate about learning ancient high Fataluku language.

Daniel Valentim Pereira joined the Many Hands International team in 2020 to oversee the digitisation project on behalf of the Valentim family. Daniel has played a pivotal role in locating items from the collection, carrying out community consultation to create interpretative text for the collection and offering insight on his father and his work.

Daniel Valentim Pereira joined the Many Hands International team in 2020 to oversee the digitisation project on behalf of the Valentim family. Daniel has played a pivotal role in locating items from the collection, carrying out community consultation to create interpretative text for the collection and offering insight on his father and his work.

Nelinha Pereira is the Strategy Lead at Many Hands International, having previously been Team Leader for more than nine years. She is a big-picture thinker, an exceptional public speaker/motivator and is passionate about seeing the Lautem region become thriving and culturally rich.

Nelinha Pereira is the Strategy Lead at Many Hands International, having previously been Team Leader for more than nine years. She is a big-picture thinker, an exceptional public speaker/motivator and is passionate about seeing the Lautem region become thriving and culturally rich.

This story was facilitated by Amy Stevenson from Many Hands International and Melbourne writer Marian Reid.

Many Hands International is a not-for-profit organisation registered in Australia and Timor-Leste. It shares a valuable and ongoing partnership with the State Secretariat for Arts and Culture, Government of Timor-Leste and is accredited by the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Funding for the Vaihoho digitisation project is from the Modern Endangered Archives Program at UCLA.