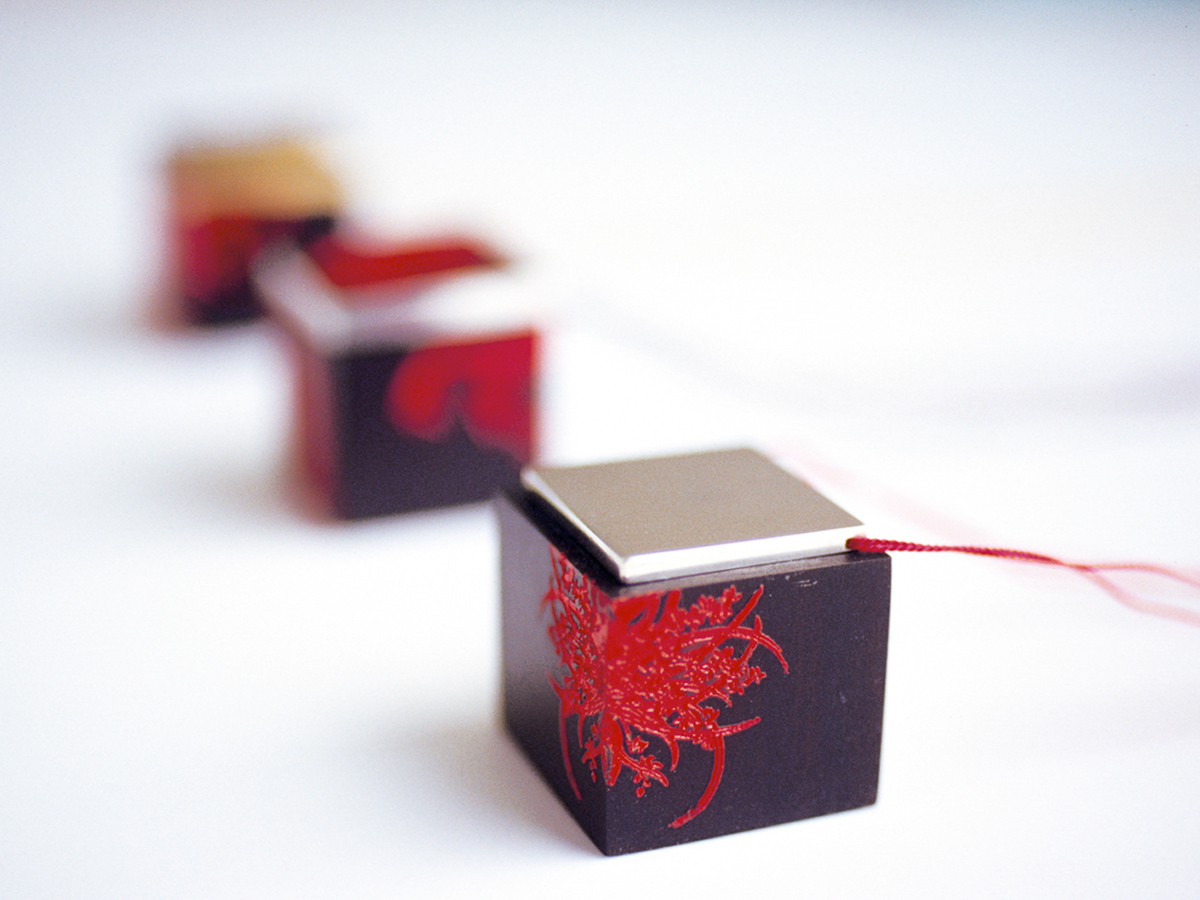

Toru Kaneko, Small Boxes, 2018, Japanese metal alloys, overall 10 x 8 diameter, Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Beginning with the Japanese animation Spirited Away, Bic Tieu traces her fascination for the magic of the box in Japanese craft and discovers how it connects humans and nature.

The scene is indelibly printed in my memory. A young girl enters the boiler room of a traditional bathhouse in the spirit world to confront Kamaji and his workers, susuwatari (tiny black soots with big round eyes). Kamaji, is an old man with six long arms, he looks like a spider and is responsible for operating the furnace and making herbal infused water. He uses his many arms to simultaneously rotate the wheel and grind herbs using a rolling mortar. These herbs are stored in box draws which pattern the walls in the boiler room.

The girl is ten-year-old Chihiro and she is the hero of a Japanese film animation Sen no Chihiro no Kamikakushi (Spirited Away). For me, it resonates with the real-life memory of visiting our local Chinese herbal medicine shop in Cabramatta. There was always an elderly man behind the counter along with scales and abacus.

There are many fantastical scenes in Spirited Away. The story is set in a world of kami (god) in Japanese Shinto folklore. Hayao Miyazaki intermixes otherworldly scenes and modern familiar images, symbolism with nature and storytelling in an imaginary way. This was my introduction to Japanese visual culture, folklore and traditional crafts.

Fascination with Japanese popular culture led me to other discoveries and into the world of the kawai culture of Hello Kitty and Keroppi. Hello Kitty and Keroppi are popular fictional characters invented by the Japanese Sanrio company. I still have my Keroppi metal box, it still stores my drawing apparatus. I just thought it was so cool to have a box pencil case growing up.

In my formative years as a design student, I discovered Japanese design and craft objects, including the world of lacquer and metal and boxes. Both these traditional art forms have continued to intrigue and inspire my practice and aesthetics today.

During my tertiary years, I was introduced to a catalogue collection, East Asian Lacquer. The book contained beautiful lacquerware from the Herbert and Florence Irving collection. In this book, I was enthralled by Shibata Zeshin’s depiction of floating boats and waves on a five-tiered jūbako (food box). Zeshin is considered the most revolutionary lacquer artist for his time in Edo, particularly for the revival of lost complex lacquer techniques. The Edo period (1603-1868) produced many box designs using the distinctive maki-e (sprinkled picture) decorative technique. Maki-e lacquer were considered luxurious and associated with upper-class life in feudal Japan.

Literacy and calligraphy were highly valued, which explains the high production of suzuribako (writing box set with inkstone, brush and water-dropper). Personal accessories like the inro (small tiered case hung from the waist) and tebako (accessory box) were also common in maki-e lacquer. Currently, showing at the National Gallery Victoria in the Pauline Gandel Gallery of Japanese Art is an extraordinary kai-awase (shell matching game set) and pair of kai-oke (large lacquer box for storing shells).

The enchanting illustrative depictions of both the box form and surface design were a great inspiration. My final project at university was an attempt at translation. Far from close, my curiosity and desire led me to learn the maki-e techniques and applications of lacquer. I received a formal two-year training residency at the Unryuan Kitamura Koubou between the years 2009 – 2011. I was immersed in the crafts, research and making. It took seven months working on a natsume (tea box) and then one-year full time making a kougou (small box).

Final year project, Integrated Box Pendant Series, 2002, acrylic paint, ebony, gold, silk cord, silver, All within 26 x 25 x 25 mm.

More recently in 2018, I had the opportunity to return to Japan to do some fieldwork as part of my PhD candidature. I was interested to learn about boxes from the perspective of Japanese practitioners in the craft field. This included a workshop with metal artist, Toru Kaneko-sensei. I focused on learning about Japanese alloys and patination. I was particularly in awe of the four boxes in his studio.

Toru Kaneko, Small Boxes, 2018, Japanese metal alloys, overall 10 x 8 diameter, Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Each pair has a soft taper and contrasting versions of one another almost like the yin and yang. The surface design with neat perfect gradient spots inlayed into the sheet metal and flawlessly encases where the lid and base connects.

I think of fireflies dancing over a rice paddy field. I am transported to when I first saw fireflies in Wajima.

This idea takes me to the philosophy by Kawai Kanjirō. Kanjirō was a Japanese potter and one of the founding members of Mingei (Japanese Folk Craft Movement). He believed that, “any work of art belongs to everyone, because it is whatever each person sees in it.” (Kawai, n.d., 13) I agree. The visceral feeling expressed through the technical sophistication of metalwork stirs awe and wonderment.

When I asked Kaneko-sensei about his thoughts on boxes, he explained to me that it is common for metal artists in Japan to create vessels and containers. Kaneko-sensei emphasised, “For me it is important that the box have a relationship of outside and inside. It is exciting to imagine the inner space from the outside. That imagination is infinite.” (Kaneko 2018) This metaphorical perspective is evident in Kaneko-sensei’s practice. His ability to reimagine metal is inspirational.

I also asked the same question to Takashi Wakamiya, a Japanese lacquer researcher and designer. He believes that the box is a symbol of Japanese culture and conduit between human and nature: “the box has inner and outer sides.” (Wakamiya 2018) Through his contemporary lacquer forms, Wakamiya-san conveys that lacquer is a tool to connect with nature and ancestry. Boxes are physical objects that require the action of opening to reveal the content.

Perhaps the significance of boxes in Japanese culture and metal and lacquer crafts can be related to traditional packaging. The Japanese author, Hideyuki Oka documented disappearing traditional forms of utilitarian packaging in his famous book, How to Wrap Five More Eggs. Oka argued that objects are valued regardless of their worth and this was expressed in the care, design and culture of packaging. Oka pointed out that “traditional Japanese packaging is the aesthetic consciousness of propriety. This is a result of considering wrapping and packaging as a sort of sacred ritual.” (Oka 1975, 12) This concept is connected to the Japanese psyche of purification, cleanliness and Shintoism. One can imagine how this respect for containing, wrapping and transporting objects crosses through other aspects of Japanese social and cultural life. This idea can help us to understand why boxes are valued in the crafts.

What I have observed in Japanese surface design is the depiction of nature. Traditional packaging utilised materials from the everyday like bamboo leaf and straw. The art of wrapping is about interpreting nature using our hands. In the lacquer and metal boxes that I have studied, a recurring theme is the transience of the seasons. These visual narratives give insights into culture, folklore, and social history. Boxes preserve Japanese culture, the human experience and technical material knowledge.

Toru Kaneko, Small (incense) Box, 2011, silver with gold detailing, Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Boxes have a function. They are containers, used as packaging, handled and opened. Boxes are secondary to the content they hold. However, the boxes discussed here are also crafted objects in themselves. They require time and accrue years of craftsmanship and design to achieve the outcome. Kaneko-sensei’s thoughts that within a box, “a magnificent story is also hidden.” (Kaneko 2018) Although Kaneko-sensei may be referring to the imaginative proposition proposed, I think otherwise. I consider the “magnificent story” to be the hands, heart and head behind the maker’s journey.

I can only speculate how these boxes were made. Creating gradients in metal requires great skill and understanding of chemical patination processes to achieve the distinctive colours that are unique to metalwork in Japan. It is also creating form and colours with a minimal amount of soldering. I have learnt the basic mixing of alloys and special joining techniques to achieve hues of black and grey from my sensei. Even at the foundation level, the technical requirements are high. I still have years and years to practice.

A view of armour accessories worn by the samurai class reveals outstanding use of metallurgy. For example, the tsuba (sword fittings), a decorative feature that mounts onto the sword. These fittings showcased the design, concept and superior technical abilities.

Boxes are not easy to make. As Wakamiya-san would say, “the box is a very effective shape when measuring the technical strength.” (Wakamiya 2018) In Kaneko-sensei’s work, I imagine how he makes individual gradient circles. The circles then would be inlaid into sheet metal. This is followed by construction work and different silversmithing processes. The organic box would require raising and planishing to bring the sheet into a three-dimensional form. Whereas the hexagonal box would require scoring and bending. The final stages would require polishing and chemical oxidisation to bring out the desired colours.

I think there is a charm about not knowing. The mystery behind the craftsmanship adds to the box’s enchantment. I return to Kanjirō thoughts on making. He “believes that only through the discipline of unrelenting work can come the truth of art in which beauty has been achieved unconsciously and effortlessly.” (Kawai, n.d., 15) He further remarks that “When you become so absorbed in your work that beauty flows naturally from within… then your work truly becomes a work of art.”

Kaneko-sensei’s boxes express his love for metal and nature. They bring delight to hold, open and marvel. I think about the functionality of the box here and its reverence for craftsmanship. Boxes are special objects. They keep safe our treasures. However, when they are made by hands with incredible skill, they become objects of beauty and objects of contemplation, transporting our minds and stirring our imaginations.

Further reading

Kaneko, Toru. 2018. Japanese Surface Metal and Lacquer Techniques, Questionnaire.

Kawai, Kanjirō. n.d. We Do Not Work Alone: the thoughts of Kanjiro Kawai. Translated by Yoshiko Uchida. Gojozaka Kyoto Japan: Kawai Kanjiro’s House.

Miyazaki, Hayayo. 2001. Spirited Away. Toho

Oka, Hideyuki. 1975. How To Wrap Five More Eggs: Traditional Japanese Packaging. New York and Tokyo: Wetherill.

Tatsufumi, Yamazaki. 2021. “A Golden Opportunity.” National Gallery of Victoria. November 25, 2021.

Wakamiya, Takashi. 2018. Japanese Surface Metal and Lacquer Techniques, Questionnaire.

Watt, James C.Y., and Barbara Brennan Ford. 1991. East Asian Lacquer: The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

About Bic Tieu

Bic Tieu is a designer, object maker and jeweller. Her works draw on traditional and contemporary craft and design methods inspired by her Asian and Australian cultural lineages to investigate themes of personal and cross-cultural narratives. Specialising in metal technologies, manufacturing processes, traditional Vietnamese and Japanese lacquer, her practice often utilises a synthesis of these materials to create new perspectives on contemporary object making and meanings.

Bic Tieu is a designer, object maker and jeweller. Her works draw on traditional and contemporary craft and design methods inspired by her Asian and Australian cultural lineages to investigate themes of personal and cross-cultural narratives. Specialising in metal technologies, manufacturing processes, traditional Vietnamese and Japanese lacquer, her practice often utilises a synthesis of these materials to create new perspectives on contemporary object making and meanings.