With the memory of a rustic sign in a front yard along a highway the search for an obscure basket maker turned out to be a more than interesting enterprise. It was to be one of those occasions when the apparently ordinary becomes extraordinary, where the everyday somehow becomes somewhat exotic. More to the point, it became a hunt of a kind where insights into some remarkable storytelling can be gleaned.

A room can never really be empty because it is always full of potential. So too it is with any hunt. When a wispy white feather rides upon the air currents, it just floating there can fill a vast room – and especially so if it is a “whitebox” art gallery. That floating feather, or a memory of a sign on a fence, can fill vast spaces right up. There will always be hints in the feather’s story, even in a memory of a sign, just by it being there and almost inevitably there is much to ponder upon. Nothing is both impossible and an impossibility. So, what seems to be an emptiness is nothing of the sort. In looking for missing stories in a place’s history, basket making turns out to be an exploration of a rich set of ideas—primordial storytelling even. The stories attached to basket making are rich stories, surprising stories, powerful stories, people stories, sometimes there are hidden stories, and generally all of them speak of place and quite loudly.

Basket making, wickery, is primordial and it seems that we all seem to have one or two pieces of wickery somewhere in our lives. Interestingly, it seems that musing places—galleries and museums—often do not know what do with wickery. Some “wickery objects” find their way into their history collections, some, and only sometimes, find their way into “the decorative arts” collections and others can only be found in the exoticism of ethnographic cum anthropology collections. In important cultural institutions, mostly it seems, it is just easier to leave baskets out of the collecting process.

Wickery touches everyone’s lives in all kinds of ways. Yet wickery is all so often made in the workplaces of the underclasses as they labour away so very close to the material’s source. However, it is not like that in Aboriginal cultural realities. And, eventually wickery will find its way back to the earth somewhere –and always gently. “Wickery” as a technology is at once primordial and current. Despite “wickery” speaking of a particular sensibility towards materials, these sensibilities predate the emergence of ceramics and metallurgy in human histories. Wickery has never lost its currency across cultural divides down through time. It has become deeply embedded in just about every cultural consciousness and social reality.

So when it turned out that the sign by the highway proclaiming “Willow Basketry Here” belonged to one Leandro Di Lullo it was kind of unsurprising. As his somewhat extraordinary story began to unfold Leandro revealed himself as a man with his roots in one place, yet someone at one with the world in another place a long way away. Leandro was born in Abruzzo and he found his place to live his life in Launceston. In doing so, and with his basket making, he seemed to make all the connections needed to make extraordinary baskets that somehow belong equally to Abruzzo and Launceston.

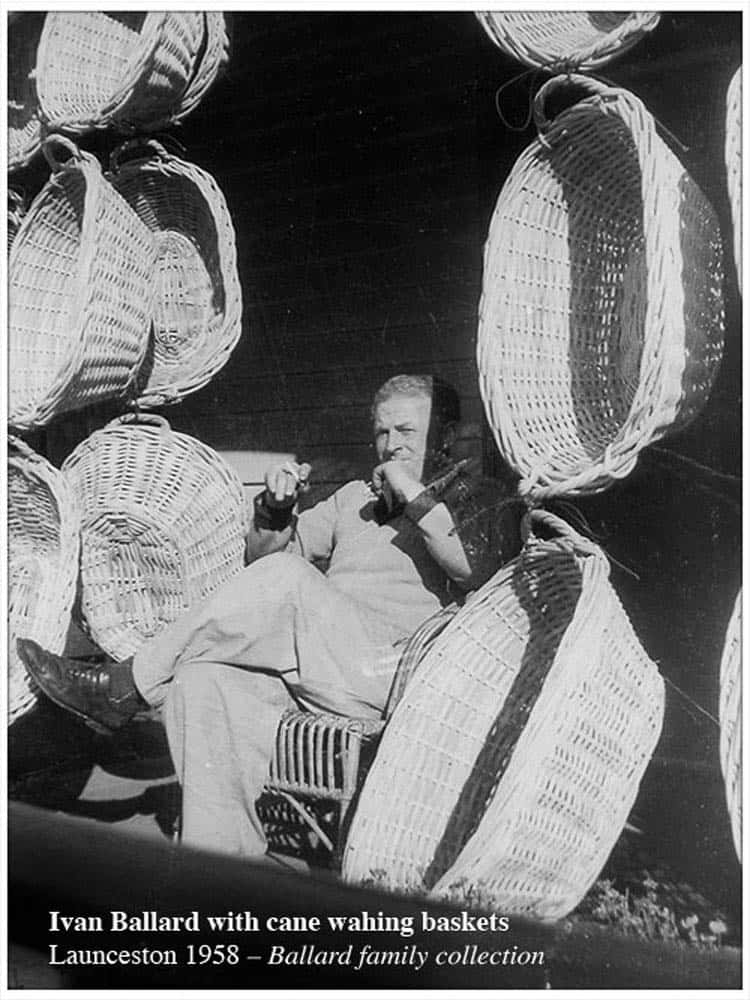

It also turned out that Leandro’s sign was not the only one proclaiming that you could buy willow baskets here. There was another sign right across town that just a little earlier in time was broadcasting that this is where you can get your Ballard Willow Baskets now. It turns out that Ivan Ballard was a fourth-generation basket maker in Launceston. His ancestor, James Ballard, was a convict who found himself in the basket business on the other side of the world in Van Dieman’s Land because of his sideline in horseless highway robbery.

Despite being largely missing in Launceston’s social histories, by the outbreak of WW1 the Ballard basket enterprise was 50 people strong and touching Launcestonians lives in almost every way. At that time on the other side of the world, Leandro Di Lullo was born in a place almost certainly unheard of by Launcestonians. Both Leandro’s family and the Ballard family carried on a cultural tradition, and a technology, that reaches back in time much further than it is possible for most of us to imagine.

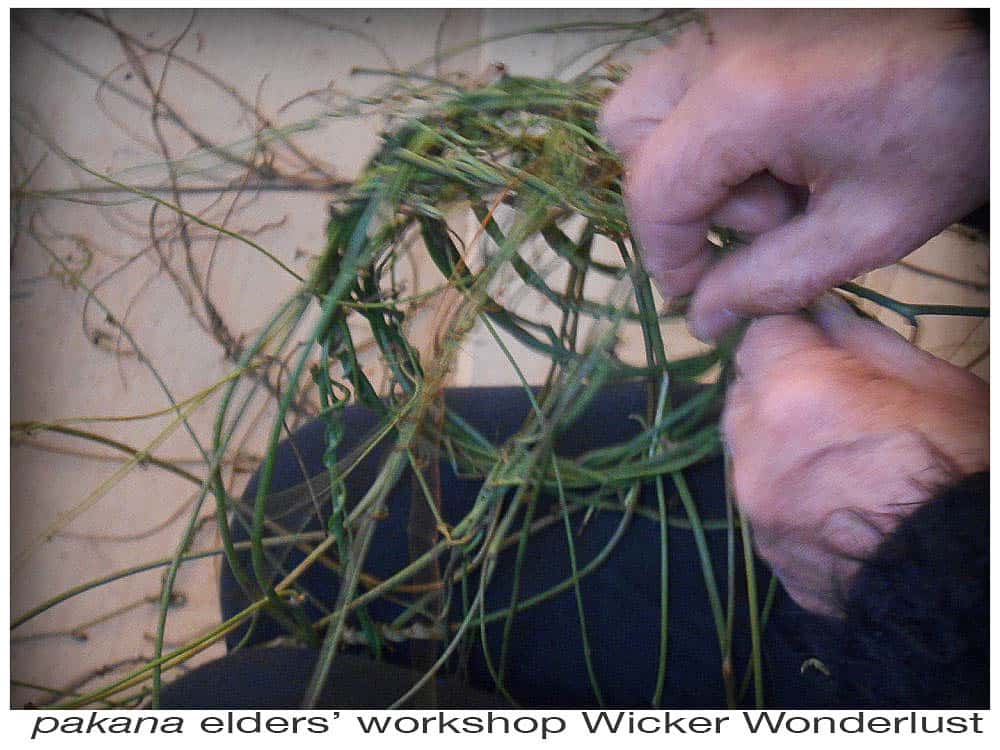

In Launceston, it turns out that if we take the time to look, there is a unique relationship between our placedness and wickery. Given Aboriginal and postcolonial sensibilities, local histories and contemporary imperatives, baskets are as full of historic and cultural contexts as they might be filled with laundry, fruit, flowers and firewood. In the case of Tasmania’s pakana and palawa people, wickery carried eggs, shellfish, tools and nowadays cultural treasures. Wickery can figure large in the cultural landscaping that makes and shapes place.

Over the course of a few months the hunt for Leandro’s stories led to an exhibition project at Design Tasmania, Wicker Wonderlust. Then came the revelation of an almost underground network of wickery-makers sprinkled throughout Tasmania along with a myriad of stories embedded in wickery and the making of it. All these stories deserve to be told and better understood.

What the wickery search revealed in part were the tensions off to one side to do with plastics. However, that is a long and complex story that demands a different paradigm to help inform and develop new understandings. Likewise, new imaginings of wickery may yet enlarge upon community-based knowledge systems in the kinds of ways that allowed ceramics and metallurgy to settle alongside wickery – and quite comfortably.

Currently, the use of social media is critical to the success of any investigation. Social media, and the rhizomatic digital connectivity it affords, provides a platform that facilitates new models of connectivity and the effective sharing of stories. In this way, it is possible to imagine that a “neowickery” might well evolve and to be built upon the mobility and the placedness found in Leandro Di Lullo’s and the Ballard family’s place in Launceston’s history. In a social dimension, wickery is typically, but not always, the work of the under-classes, the invalids, the itinerant poor, et al. Outside very narrow social paradigms, the maker’s name is typically quite unimportant and generally unknown. Even with the so-called Modern Crafts Movement of the 1960s/70s/80s, wickery makers very often had no aspirations to be known as either “artist” or “designers”. Accordingly, their work, and quite often the makers themselves, were often overlooked.

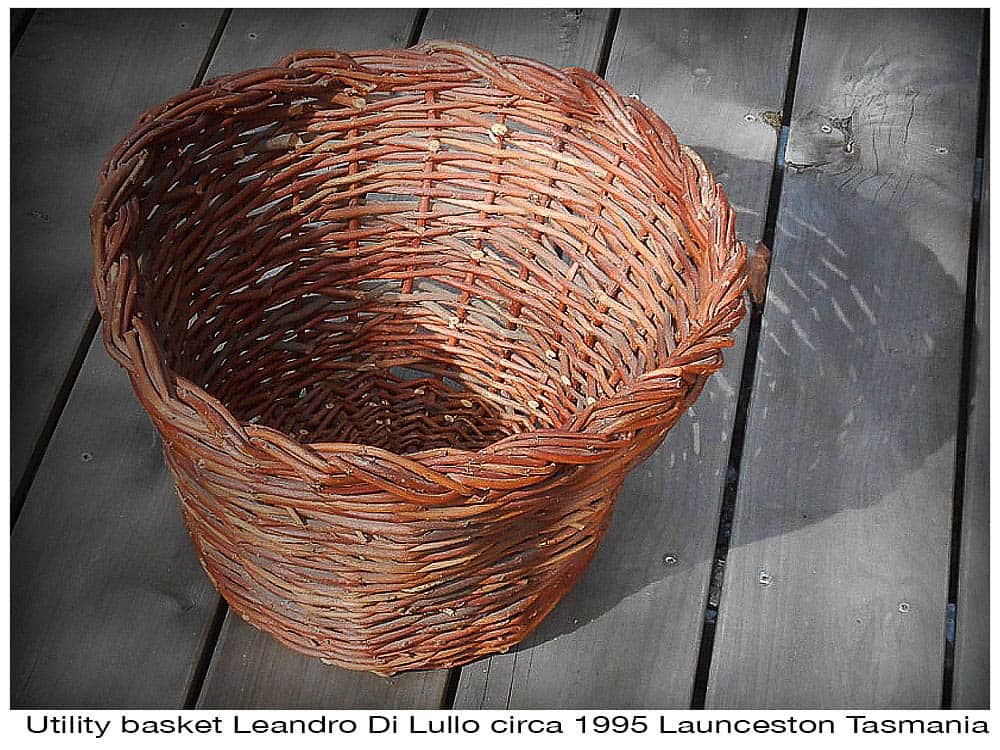

Resonating within a wickery sensibility there is something like the philosophical pillar of “mingei” to be found in Japanese cultural production. Mingei is “hand-crafted art of ordinary people”. Yanagi Soetsu discovered beauty in the everyday, the ordinary and utilitarian objects created by nameless and unknown craftsmen. According to Yanagi, utilitarian objects made by the common people are “beyond beauty and ugliness”. Typically, the mingei sensibility is to do with things made anonymously, by hand and in quantity. Typically, it is relatively inexpensive and used by ordinary people as part of their everyday daily life. Consequently, mingei almost unavoidably reflects a placedness via its materiality of place and the cultural landscape it originates within—and in a way generates. Nonetheless, there is a kind of “mingei cum wickery” equivalence to be found within cultural landscapes almost everywhere. Somewhat unexpectedly this is found in Launceston in Leandro Di Lulllo’s work. In Tasmania, more generally it is also evident albeit somewhat under the sweep of the cultural radar. It seems that generally with wickery the objects are by and large in daily use and thus there is an element a wabi-sabiness about a great many of – especially so in Leandro Di Lullo’s baskets.

Wabi-sabi is that ancient Japanese philosophy rooted in Buddhism that celebrates and accepts the imperfect, the transient, the natural. Wabi-sabi prizes things that are handmade, irregular and imperfect. While there is no direct western translation for wabi-sabi, essentially it is the art of finding beauty in the imperfect, the impermanent and the incomplete. Intuitively, it seems, those who possess wickery subliminally embrace wabi-sabiness. Leandro Di Lullo’s baskets that come to light now wear their usefulness proudly, the passage of time and their placedness is there in a wabi-sabi way.

So, when an empty room in a musing-place is somewhat unexpectedly filled extraordinarily ordinary objects, typically useful objects, that are as full of stories as they might be full of the things that need to be stored, you have a room filled with something almost undefinable. If it is as a consequence of a hunt for the stories behind roadside signage that too is extraordinary. With the memory of that sign in a front yard along a highway, that obscure basket maker, Leandro Di Lullo, and the hunt for him turned out to be a quite enlightening. The ordinary became extraordinary and the everyday somehow became somewhat exotic. So, if there is ever any doubt, remarkable storytelling, and a completness, can be found in the simplest of things – wickery especially

Author

Comments

When only four and half years old in mid 1954 I was put on the bus and sent off to Burnie State School in town. I lived in the bush up behind Burnie and my mother saw that I needed school. Other than pin pricking shapes through coloured APPM bond paper, an early and fond memory was of soaking cane and making rudimentary wicker baskets. Cane – as it was called then – was and continues to be “big along the coast”. Every home had a wicker washing basket and kits could be readily purchased in town. I know less about “placedness and wickery” than the author but do know that cane work was “big along the coast” and that it featured regularly in my late mum’s “Women’s Weekly” magazines with many “how to” sections. Crafting, a word not used those days let alone “the crafts”, was a part of making do in a post WW2 time, especially “along the coast” where it was big!

As an aside, plastic “woven look” washing baskets soon appeared in the 60’s and the wicker ones were summarily tossed out and burnt in the incinerator. Wickery became trickery and it caught on later on in the NT with Aboriginal weavers when brightly coloured plastic covered copper wire and blue woven super phosphate bags were easier to get than grasses, were readily coloured and lasted longer. Nowadays ghost netting is the new Telecom copper wire in TNQ and the Torres Straits Island’s first people communities. Crafting never stands still.

A finely woven article – congratulations.